Chapter 10 Maxillofacial Fractures

ANATOMY AND BIOMECHANICS

• The mandible and maxilla differ from the rest of the skeleton in that they contain teeth. Most of the dorsal two thirds of the body of the mandible is occupied by dental roots. The ventral third includes the mandibular canal, containing the inferior alveolar nerve and associated blood vessels. Ventral to the mandibular canal there is only a single layer of dense cortical bone.

• The lower jaw consists of two mandibles, joined at the symphysis, which consists of a fibrocartilaginous pad between the slightly irregular bony surfaces.1 The symphysis remains a true joint throughout life in the dog and cat. The term symphyseal separation is therefore more accurate than symphyseal fracture. The mandible consists of a body, which is the tooth-bearing part, and a ramus, which is the caudal, non–tooth-bearing part.2 The body of the mandible is often referred to incorrectly as the horizontal ramus. The ramus of the mandible contains three prominent processes: the coronoid process, on the dorsal aspect, the condylar process caudally, and the angular process caudoventrally.

• The term maxillary fractures in veterinary oral surgery often refers to fractures involving the incisive, palatine, zygomatic, frontal, and nasal bones, in addition to the maxillary bone proper.

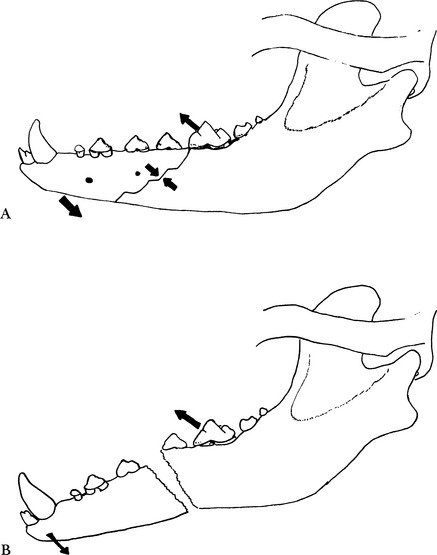

• The temporal, masseter, and medial pterygoid muscles are responsible for closing the mouth. Because the muscular insertions are located on the caudal part of the mandible, this part in particular will be lifted when a fracture of the body of the mandible has occurred. The relatively small digastric muscle is responsible for opening the mouth. The static force exerted by this muscle, together with that of the geniohyoid and mylohyoid muscles and the force of gravity, tends to pull the rostral fragment of a fractured mandible in a caudoventral direction. Because of the forces exerted by the masticatory muscles, the direction of the fracture line determines whether a fracture is relatively stable (Fig. 10-1, A) or unstable (Fig. 10-1, B).3,4

• The forces exerted on the mandible are also exerted on the maxilla. However, the distribution of these forces is much different, and it is generally accepted that the maxilla is subject to much less strain.

INITIAL MANAGEMENT

• Concurrent injuries to the head and other body parts are common. The patient should be fully examined in accordance with accepted clinical practice regarding trauma cases. Concomitant injuries may be life threatening and may require postponing definitive repair of the maxillofacial fracture.

• The diagnosis of a fracture of the mandible usually can be made by inspection and palpation. The nature and extent of the fracture can be further assessed by gentle palpation once the patient is under anesthesia prior to surgical treatment.

• Radiologic examination using dental film is indicated to visualize the fracture site and to diagnose concomitant dental trauma. Fractures involving the ramus or condylar process of the mandible and maxillary fractures are visualized best using computed tomography.

• Most maxillofacial fractures are of traumatic origin. Pathologic fractures associated with neoplasia occur occasionally. Relatively more common, however, are fractures of very weakened mandibles associated with severe periodontitis. Radiography is essential to recognize pathologic fractures.

• Fracture of the mandible is a most painful condition because of the inherent sensitivity of facial tissues. To lessen the patient’s discomfort and to prevent further damage to the soft tissues, the fracture should be reduced temporarily and immobilized as soon as possible. Gross reduction can be obtained by gentle palpation using the occlusion of the canine teeth as a guide. A simple tape muzzle is then applied to maintain reduction (see further).5,6 This may be combined with a surgical technique for nutritional support, such as an esophagostomy tube, especially if the patient is in unstable condition and if it is unclear when definitive repair will be possible.

PRINCIPLES OF MAXILLOFACIAL FRACTURE REPAIR

• The management of fractures of the mandibular body should be aimed at the restoration of normal occlusion. The correct interdigitation of teeth is essential. It is imperative that the occlusion be inspected and taken as a guide during surgical repair of mandibular and maxillary fractures.

• An important goal in the management of maxillofacial fractures is to restore normal function as soon as possible after the traumatic insult.

• Most mandible fractures in the dog are open to the oral cavity and inevitably contaminated. The prophylactic use of antibiotics in compound fractures has been shown to be of value in preventing infectious complications in humans.7 Removing devitalized tissue will enhance healing and may, to a large extent, prevent later complications.8 The surgical debridement of soft tissues should be very conservative, because the blood supply and healing capacity of oral tissues are excellent. Small loose pieces of bone should be removed if they do not contribute to stability of the repaired fracture. If they are retained, it is important to preserve their soft tissue attachments and to ensure that they are rigidly fixed.

• A tooth involved in a fracture line may be luxated and loose. In that case, the tooth should preferably be removed. If the tooth is not mobile, it usually is left in place, because it will contribute to the stability of the fracture fixation. If a tooth involved in the fracture line is retained, it should be monitored carefully for any subsequent evidence of periodontal or endodontal lesions, and appropriate treatment should be instituted as soon as this is recognized.9,10

• During surgical repair of maxillofacial fractures, the surgeon should be aware of the teeth and other anatomic structures and make every effort to avoid iatrogenic damage.

• Severe dental disease, periodontal disease in particular, may have a marked effect on the amount and density of the jaw bone.10 The quality and amount of bone available are important factors in selecting orthopedic implants in maxillofacial surgery.

• Many maxillofacial fractures in dogs and cats can be managed conservatively, but many patients would benefit from skillful surgical intervention to achieve a more rapid return to normal function and to minimize the risk of malocclusion. Contraindications for surgical repair include a deciduous dentition, because it is nearly impossible to use implants without damaging the developing tooth germs.

ANESTHETIC MANAGEMENT AND POSITIONING FOR MAXILLOFACIAL FRACTURE REPAIR

General Comment

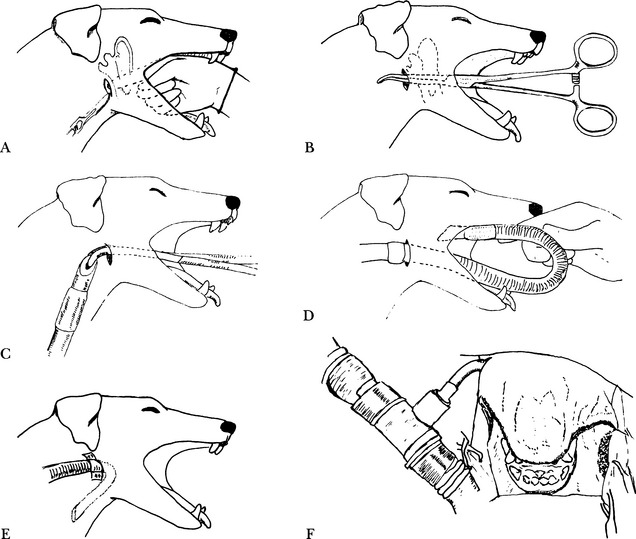

• The importance of checking the occlusion during surgical repair of mandibular fractures has already been mentioned. The presence of an oral endotracheal tube makes this impossible. However, intubation with a cuffed endotracheal tube to prevent aspiration is highly recommended during any oral surgery. Passing the endotracheal tube through a pharyngotomy incision satisfies both requirements.3,11

Indications

• Pharyngotomy endotracheal intubation is indicated for all maxillofacial fracture repair procedures, with the exception of mandibular symphysis separation.

Technique

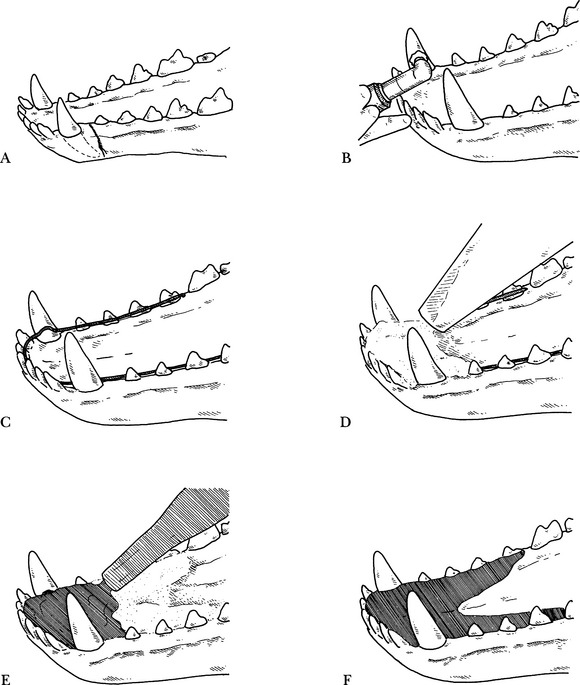

Step 1—With the patient under general anesthesia, the index finger is placed caudodorsal to the angle of the mandible and caudomedial to the hyoid apparatus, and a small skin incision is made over the finger (Fig. 10-2, A).

Step 2—The finger is replaced by a long curved forceps, which is pushed through the pharyngeal wall and overlying tissues (Fig. 10-2, B).

Step 3—The wire-reinforced endotracheal tube is grasped with the forceps and drawn into the pharynx (Fig. 10-2, C).

Step 5—Two pieces of adhesive tape are placed around the proximal end of the endotracheal tube and it is sutured to the skin (Fig. 10-2, E).

Patient Positioning

• Dorsal recumbency is indicated for the repair of most mandibular fractures, with the exception of fractures involving the condylar process, where lateral recumbency is preferred. The oral cavity can be lavaged with copious amounts of chlorhexidine gluconate solution. With the surgical drapes fixed to the upper lips, it is possible to check the occlusion during mandibular fracture repair (Fig. 10-2, F).

Complications

• Damage to the salivary glands and neurovascular structures at the pharyngotomy site. This can be avoided by careful blunt dissection with the long curved forceps.

TAPE MUZZLE FOR MAXILLOFACIAL FRACTURE STABILIZATION

Indications

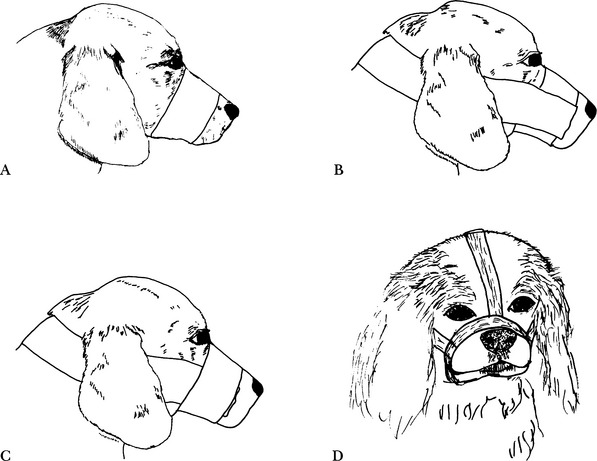

• The use of a tape muzzle is well established in the treatment of mandibular fractures.5,6,12 By closing the mouth in occlusion, the fracture fragments are brought into alignment and some immobilization is achieved.

• It is also indicated for the definitive treatment of stable and minimally displaced fractures, especially in patients with a deciduous dentition.

• The use of a tape muzzle can be considered as means of additional support in cases in which internal fixation did not achieve optimal stabilization.

Technique

Step 1—The first strip of tape (adhesive side out) is applied around the muzzle; tape wide enough to encompass most of the patient’s muzzle is used (Fig. 10-3, A).

Step 2—Two strips of tape, stuck together, are passed behind the ears and attached to the adhesive surface of the first strip (Fig. 10-3, B).

Step 3—A strip of tape, adhesive side in, secures the tape loop to the first strip of tape around the muzzle (Fig. 10-3, C).

Step 4—In brachycephalic dogs and cats, an additional double strip of tape, from the dorsum of the nose over the frontal region, is helpful (Fig. 10-3, D).

• A possible variation includes an additional piece of tape applied as a throat latch and attached by threading it around the cheek portion of the retaining piece of tape and passing it ventrally beneath the throat.

• A 5- to10-mm gap is left for the tongue to allow the patient to lap liquefied food. Alternatively, the mouth can be closed completely and the patient fed through a pharyngostomy, nasogastric, esophagostomy, or gastrostomy tube.

Complications

• Dyspnea in brachycephalic patients is possible while the mouth is being maintained in a nearly closed position.

SYMPHYSEAL SEPARATION REPAIR: CERCLAGE WIRING TECHNIQUE

Technique

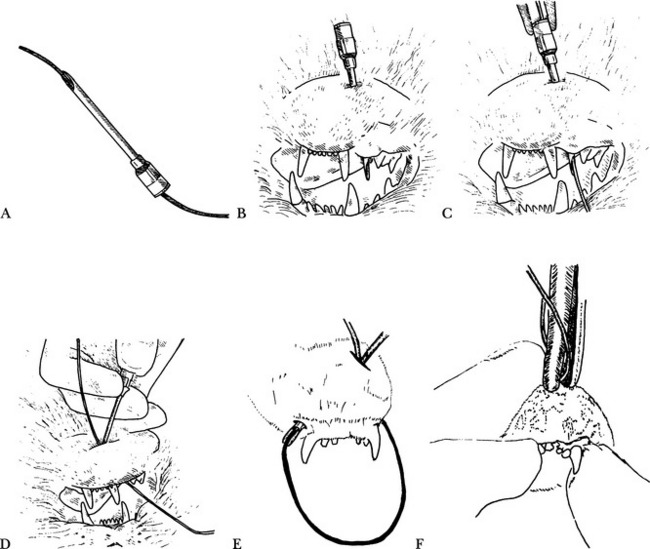

Step 1—The wire is passed into the bore of the needle at the hub to make sure the wire fits through the needle (Fig. 10-4, A).

Step 2—A 10-mm incision is made at the ventral midline, and the needle is inserted through the skin of the mandible and passed along the surface of the bone, directed dorsally to the buccodistal side of the canine (Fig. 10-4, B). The bevel of the needle should be facing the bone, thereby avoiding damage to the mental nerve with the sharp needle tip.

Step 3—The needle is grasped with wire-twisting forceps while the wire is pushed up through the needle (Fig. 10-4, C). The needle is removed, leaving the wire between the bone and skin and exiting both at the access and exit sites.

Step 4—The needle is reinserted at the ventral midline into the skin of the mandible and directed dorsally to the buccodistal side of the opposite canine, in a fashion similar to that of the first insertion (Fig. 10-4, D).

Step 6—The needle is removed, leaving a loop of wire behind. On the dorsal aspect, the wire remains exposed to the oral cavity.

Step 7—Reduction is achieved and digitally maintained while the wire is tightened, using a wire-twisting forceps or small orthopedic wire twister, observing the standard guidelines for effective wire tightening (Fig. 10-4, F).

Step 9—The wire is not bent in order not to decrease the tension. The skin wound edges are approximated to cover the wire twist and sutured with two to three single, interrupted sutures.

Complications

• Malocclusion due to incorrect alignment before the wire is tightened; this can be prevented by evaluating the occlusion and the mandibular incisive plane as the wire is tightened.

• Canine malocclusion in the presence of correct incisor realignment is suggestive of a concomitant caudal mandibular fracture.

Aftercare

• Skin sutures can be removed after 10 days. Oral cavity fluids and bacteria may wick along the surface of the wire, resulting in a small draining tract at the ventral aspect of the chin. A 0.05% chlorhexidine gluconate solution can be used as an oral antiseptic rinse and to keep the skin wound area clean.

Variations

• Many variations on the simple cerclage wire technique have been described, such as placing the wire knot on the lateral aspect of the mandible.14 Variations have also been described for cases in which fractures of parts of the incisive section of the mandible occurred in addition to the symphyseal separation during the traumatic incident.13 Interdental wiring techniques, augmented with and held in place by acrylic or composite resin, may be advantageous in cases in which incisors or canine teeth were luxated or avulsed in the process.15 In the case of a comminuted fracture with multiple small bone fragments and luxated teeth, a partial mandibulectomy can be performed.16

FRACTURES OF THE BODY OF THE MANDIBLE

Methods of Repair

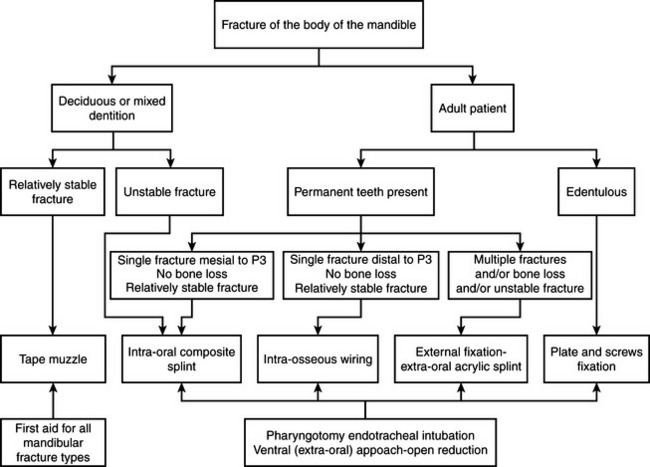

• A wide variety of surgical and nonsurgical methods have been described for the treatment of fractures of the body of the mandible in the dog and cat. An in-depth discussion of the advantages, disadvantages, and technical details of each are not within the scope of this text. The following protocol is suggested (Fig. 10-5).

Surgical Approach to the Body of the Mandible

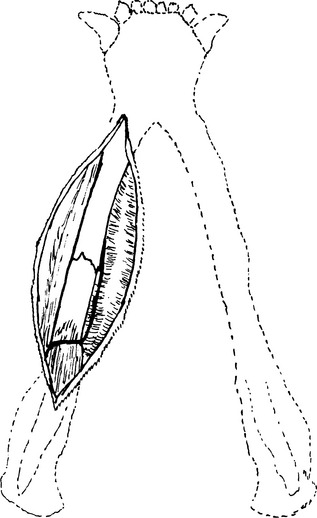

• With the patient in dorsal recumbency, the standard ventral approach to the body of the mandible is simple and affords excellent exposure.17 The incision is made through the skin overlying the ventral edge of the mandible, from the level of the canine tooth to as far caudally as necessary for adequate exposure of the fracture site. Subcutaneous tissue and platysma are incised and the soft tissues reflected on both sides of the mandible. Care should be taken to avoid traumatizing the mental nerves and blood vessels rostrally, and the facial vein caudally (Fig. 10-6).

• On completion of the procedure, the soft tissues are apposed over the bone and implants and sutured.

INTRAORAL SPLINTS

General Comments

• The use of an intraoral acrylic splint in the management of maxillofacial fractures in small animals is well established.4,18–20 The original technique involved making an impression and from that a cast model of the dentition.4 An acrylic splint is then made on the model, after which it is installed in the mouth of the patient. Alternatively, and more practically, acrylic or a composite restorative material may be cast directly in the oral cavity to create an intraoral splint.18–20

• The indirect fabrication of the cast is a longer procedure and is best suited to a team approach. Bone movement at the fracture site before, during, and after the impression is taken may complicate the installation of the splint. The additional length of anesthesia time is also a consideration.

Indications

• Relatively stable fractures of the mandible mesial to the first molar, or preferably mesial to the third premolar.

Materials for Intraoral Acrylic Splint: Direct Technique

• Cold-cure acrylic (Jet Denture Repair Acrylic, Lang Dental, Wheeling, Ill.). Alternatively, a light-cure acrylic (Triad VLC, Dentsply-Trubyte, York, Penn.) may be used, which offers the advantage that there is less heat production, but which is time consuming to apply because of the long curing time.

• Low-speed handpiece with acrylic cutting laboratory burs 75-080, 78-060 (Brasseler USA, Savannah, Geo.).

Intraoral Acrylic Splint: Direct Technique

Step 1—Appropriate radiographs are obtained, misalignments are corrected, and other treatment is performed as indicated (Fig. 10-7, A). The tooth surfaces should be clean.

Step 2—The patient is placed in sternal recumbency. The coronal surface of the teeth (usually the canines and larger premolars) may be used for retention of the splint along with wiring techniques. The bonding sites are identified: the bulk of a mandibular splint should be on the lingual aspect of the teeth included, while a maxillary splint should primarily be created on the buccal aspect, in order to prevent or minimize occlusal interference.22 Teeth are scaled and then polished with a slurry of flour pumice (Fig. 10-7, B). The oral cavity is rinsed well.

Step 4—Wire is bent from tooth to tooth to act as a support for the acrylic (Fig. 10-7, C); alternatively, a wiring technique can be used (see further).

Step 5—A light coat of petroleum jelly is applied to exposed soft tissue surfaces (avoid the previously placed wire) and the coronal surfaces of the teeth on the opposite jaw. Boxing wax can also be applied on the buccal and lingual gingiva to prevent the acrylic from running off.

Step 8—Additional powder and liquid are alternately applied until the appliance has been built up for sufficient strength (Fig. 10-7, F).

Materials for Intraoral Composite Splint

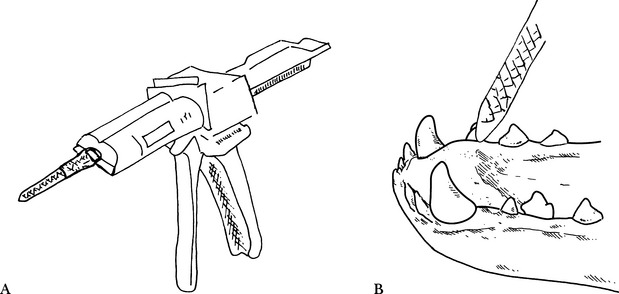

• Self-curing, composite temporary restorative material (Fig. 10-8, A) (Protemp Garant, ESPE, Plymouth Meeting, Penn.).

Technique for Intraoral Composite Splint

Step 1—Appropriate radiographs are obtained, misalignments are corrected, and other treatment is performed as indicated. The tooth surfaces should be clean.

Step 2—The patient is placed in sternal recumbency. The coronal surface of the teeth (usually the canines and larger premolars) may be used for retention of the splint along with wiring techniques. The bonding sites are identified: the bulk of a mandibular splint should be on the lingual aspect of the teeth, while a maxillary splint should primarily be created on the buccal aspect, in order to prevent or minimize occlusal interference.22 Teeth are scaled and then polished with a slurry of flour pumice. The oral cavity is rinsed well.

Step 4—The composite temporary restorative material is applied using an automix delivery system (Fig. 10-8, B).