8 Management of Heart Failure

Most heart diseases in dogs are chronic; despite this, it is common for clinical signs to develop suddenly. The reasons for this are varied. Pets are largely sedentary, and, consequently, subclinical heart disease can progress until a minimum of stress or exertion provokes signs of cardiac dysfunction. Additionally, subtle changes in respiratory rate and character are difficult for pet owners to recognize. Regardless, it is common for chronic disorders such as degenerative mitral valve disease and canine dilated cardiomyopathy to result in clinical signs that are apparently sudden in onset and necessitate emergent management. Such a presentation might be best described as decompensation rather than acute heart failure. There are, however, a few examples of truly acute CHF in dogs. Rupture of a first-order mitral valve chorda tendinea can result in sudden elevations of left atrial pressure and acute, left-sided CHF. Similarly, destruction of the aortic or mitral valve by an aggressive infective lesion can also cause acute heart failure. Regardless of the precise pathogenesis, the sudden development of cough or dyspnea related to heart failure is an important veterinary emergency.

Respiratory distress related to pulmonary edema is the most consistent historical finding in severe CHF. Syncope, lack of appetite, cough, and depression may also be part of the animal’s medical history. With the exception of cardiac tamponade, which is discussed in Chapter 7, the onset of right-sided CHF is in general more insidious and less often prompts urgent veterinary evaluation.

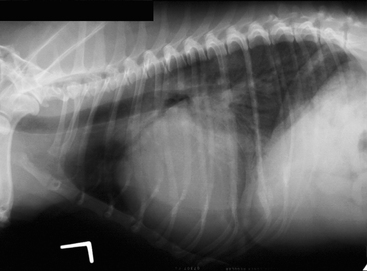

The clinical signs of left-sided heart failure and primary respiratory tract disease are superficially similar. Because aggressive diuretic therapy can be lifesaving in CHF but harmful in the setting of respiratory tract disease, an accurate diagnosis is essential. A noninvasive diagnosis of left-sided CHF can be made radiographically; left atrial enlargement in the presence of pulmonary opacities compatible with edema is diagnostic (Fig. 8-1). Sometimes, the fragile clinical status of the animal is an impediment to careful radiographic examination and the risk-benefit ratio is in favor of empirical therapy. In these cases, a careful assessment of the history and physical examination findings is essential. Before empirical therapy, it is important to determine that a diagnosis of acute CHF is at least plausible.

Heart failure results from heart disease; therefore it is important to consider whether it is likely that the animal has a cardiac disorder that could reasonably result in heart failure. The most common acquired heart diseases that result in left-sided CHF in dogs are dilated cardiomyopathy and degenerative mitral valve disease; the former most commonly affects middle aged, large-breed dogs, whereas the latter affects elderly, small-breed dogs. If CHF is present in an elderly small-breed dog, the murmur is usually loud. Conversely, it is extremely unlikely for an elderly small-breed dog to develop CHF in the absence of a murmur; in these cases, signs such as cough and dyspnea are almost always the result of respiratory tract disease. Dogs with dilated cardiomyopathy may have relatively subtle auscultatory findings. In these instances, a soft murmur or a gallop rhythm may have great clinical importance.

Preload is the force that distends the ventricle at end-diastole. It is approximated in the living animal by end-diastolic ventricular pressure or volume. Although end-diastolic left ventricular pressure can be estimated through the measurement of the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, this is not routinely measured in small animals. However, the concept of preload and its pharmacologic manipulation is theoretically useful.