18 LYMPHOID LEUKEMIAS

1 What is the hallmark of lymphoid leukemia, and how is this disorder distinguished from lymphoma?

Lymphoid leukemia is primarily a disease of bone marrow, peripheral blood, and in later stages, tissues outside the marrow. In most cases, lymphoid leukemia is thought to arise within bone marrow, but it may infrequently arise within the thymus or spleen and subsequently colonize the bone marrow.1 Classically, lymphoid leukemia is distinguished by the presence of high numbers of circulating neoplastic lymphoid cells in peripheral blood. Aleukemic and subleukemic forms do occur, in which neoplastic cells are absent or are not visualized in significant numbers in peripheral blood, respectively, necessitating evaluation of bone marrow for definitive diagnosis.

Lymphoid leukemia and lymphoma may both involve tumors of B cell, T cell, or null cell phenotype.2,3 In addition, both may involve mature-appearing or undifferentiated cells. The only means by which lymphoid leukemias can be routinely distinguished from lymphomas is with appropriate disease staging to determine sites of tumor involvement. Bone marrow involvement must be documented to diagnose leukemia. Lymphoid leukemia cannot be distinguished from stage V lymphomas characterized by extensive bone marrow involvement.

2 How are lymphoid leukemias classified?

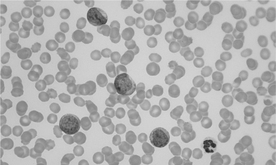

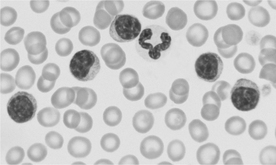

Leukemias are classified into acute or chronic categories according to the degree of maturity or differentiation of the neoplastic lymphoid cell involved. Acute lymphoid leukemia (ALL) arises from proliferation of early, undifferentiated, immature progenitor cells, resulting in the arrest of lineage development (Figure 18-1). In contrast, chronic lymphoid leukemia (CLL) arises from late-stage precursors, resulting in proliferation of fairly well-differentiated cells4 (Figure 18-2). In animals the acute form of lymphocytic leukemia is more common than the chronic form.1

The French-American-British (FAB) Cooperative Group has defined a classification scheme that further subdivides ALL by patient age and neoplastic cell morphology into three subdisorders termed L1, L2, and L3. This system may be applied to ALL in veterinary patients, but prognostic usefulness is questionable.1,2 Alternatively, lymphoid leukemia may be classified by neoplastic cell phenotype into B cell, T cell, or natural killer (NK) cell phenotype. Prognostic utility of leukemia phenotyping in veterinary species remains to be seen.2

3 How do acute and chronic leukemias differ in behavior?

Behavior of acute and chronic lymphoid leukemia is distinct. Acute leukemias tend to exhibit more aggressive behavior and rapid progression than chronic leukemias. In acute forms, neoplastic cells exhibit a greater tendency to proliferate at the expense of bone marrow hematopoietic cells, ultimately resulting in myelophthisis. This manifests clinically as variable cytopenias and increased vulnerability to infection (usually secondary to neutropenia). As neoplastic cells spill into peripheral blood in increasing numbers, increased blood viscosity and thrombosis, as well as organ infiltration (particularly of liver, spleen, and lymph nodes), are possible.4

Chronic lymphoid leukemias typically exhibit a slower pattern of progression; a prodromal phase of months to years is thought to occur.1 Clinical signs are also relatively mild, and lethargy may be the only outward sign of illness.1,4 In many cases, chronic lymphocytic leukemia is diagnosed incidentally on routine hematologic evaluation. Bone marrow involvement is generally significantly less extensive, at least in the early phases of disease, than in the acute form. When present, cytopenias tend to be milder in severity.1

4 What is the incidence of lymphoid leukemia in veterinary species?

Compared with lymphoma, both ALL and CLL occur less often. Among lymphoid leukemias, ALL is more common than CLL. The reported proportion of all canine leukemias that are lymphoid in origin varies. Leukemias of lymphoid origin were recently reported to represent one third of all leukemias diagnosed in the dog.1 Another report suggests that lymphoid leukemias are the predominant type in the dog.5 Certainly among the chronic leukemias, CLL is most common in all species.4

In the cat, lymphoid leukemias make up the majority of all leukemias diagnosed. Leukemias occur more frequently in the cat overall, accounting for approximately one third of all hematopoietic neoplasia in this species,6 likely as a result of the effects of feline leukemia virus (FeLV) infection.4

ALL typically affects young to middle-aged dogs and cats, with a median reported age of 5.5 and 5 years, respectively.1 Among dogs, affected males outnumber females about three to two.5

CLL is primarily a disorder of middle-aged and older dogs, cattle, and cats.1 Median reported age in the dog is 10.5 years.1 As with ALL, male dogs have a higher rate of incidence, outnumbering affected females about two to one.5 CLL is reported only rarely in the cat and does not appear to be related to FeLV infection.6

5 Has an etiology been determined in the development of lymphoid leukemia?

Viral infection is probably the best-defined etiology associated with leukemia development in cats and cattle. Of cats diagnosed with ALL, 60% to 80% will test positive for FeLV infection.6 FeLV infection has been reported in as many as 90% of all leukemias in cats.4 Other, as yet unknown factors (possibly genetic) must act in concert with FeLV in development of leukemia, however, because tumor rates with experimental infection are much lower.4 Bovine leukemia virus (BLV) infection in cattle is associated with development of lymphocytic leukemia, although the incidence is lower than that of BLV-associated lymphoma.7

In dogs, no specific etiology in the development of lymphoid leukemia has been identified. Unlike cats and cattle, no retroviral cause has been implicated.5

6 How is immunophenotyping useful in the diagnosis of lymphoid leukemia?

In the dog, ALL is of varied phenotype. In one case series, T cell, B cell, and null cell phenotypes each constituted about one third of cases described.8 In another case series, B cell phenotype was seen in half of cases, with the other half consisting of an equal mix of T cell and null cell phenotypes of large granular lymphocyte leukemia.9 Another series documented 40% T cell, 40% null cell, and 20% B cell phenotype in canine ALL.10 A higher proportion of canine CLL is reported to be of T cell phenotype (two thirds to three quarters of cases).1,5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree