3 Localizing lesions

William of Occam (died circa 1350) pioneered the KISS (‘Keep It Simple, Stupid!’) approach to problem-solving with his philosophical principle that the fewest possible assumptions are to be made in explaining a thing. This principle is known as Occam’s razor and is used in localizing neurological lesions.

If the anatomical site of disease is not known, then testing cannot be performed in a logical, rational, cost-efficient and expedient manner (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1 The required thought process for diagnosis

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| 1. What is abnormal? | Take a history |

| 2. What body system is responsible? | Examine the animal |

| 3. Is it the nervous system? | Perform a neurological examination |

| 4. Where is the lesion? | Interpret the exam findings |

| 5. What could the lesion be? | Consider signalment, history, anatomic location |

| 6. How best to diagnose? | Consider the anatomic location |

| 7. How best to treat? | Consult textbooks and journals |

AETIOLOGY OF THE LESION

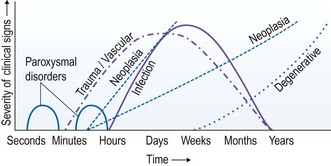

Pathological processes have typical patterns of behaviour and these can be simplistically demonstrated with graphs. These are guidelines only. Diseases have nuances and variations in clinical appearance. Textbooks only describe the common presentations (Fig. 3.1).

Do not forget the basics … co-existing disease

Interpretation of neurological signs

Interpretation of findings requires a basic understanding of how the nervous system works. Happily, there are characteristics associated with each section of the nervous system (Boxes 3.1–3.9). Make a list of the abnormalities, apply ‘Occam’s razor’, and see if the deficits can be assigned to one area of the nervous system (Fig. 3.2).