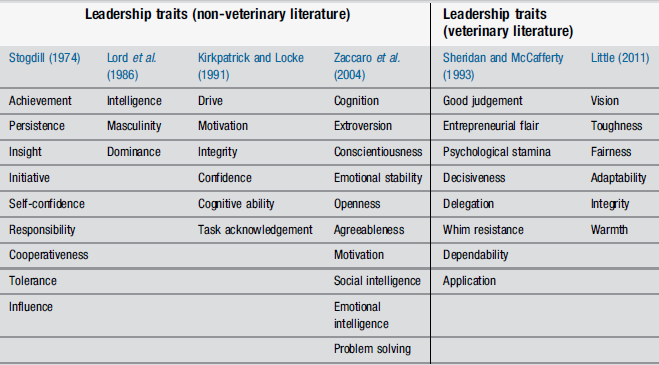

4 It is important to begin by recognizing the different perspectives, orientations and skill sets of operators, managers and leaders (Bennis and Naus, 1985; Kotter, 1990; Rost, 1991). Operators can be defined as the people who carry out the actual production or delivery of a business’s services. In veterinary practice, these are the vets that perform the consultations and surgical operations as well as the nurses and the receptionists who support them. A manager is the person who supervises and assists the operators. Managers are focused on the efficiency and accuracy with which certain outcomes are achieved by the people and the systems that deliver them. There are many potential outcomes that can be measured in veterinary practice; these include clinical outcomes (e.g. number of postoperative wound infections), commercial outcomes (turnover, profit, number of transactions), client outcomes (satisfaction scores and willingness to recommend the practice) and staff outcomes (morale, ability to perform certain tasks). Each of these outcomes is called a key performance indicator (KPI). While some KPIs are commonly used to measure performance within the veterinary profession, such as commercial outcomes, there is no absolute list of KPIs which all veterinary organizations adopt to track their progress. Indeed, in the author’s experience, a manager can make an immediate impact within their veterinary organization by simply identifying and defining which KPIs they wish to measure, and then making efforts to improve them. Traits are defined as habitual patterns of behaviour, thought and emotion (Kassin, 2003). This approach to understanding leadership evolved from the Great Man approach as a way of defining and identifying the personal characteristics which enable leaders to get people to work effectively together towards a common goal (Bass, 1990; Jago, 1982). Various researchers have identified a range of traits, and some of these are summarized in Table 4.1. Within the veterinary literature some authors have listed traits which they assert are critical to leadership and management within the veterinary context (Little, 2011; Sheridan and McCafferty, 1993); these are also included in Table 4.1. Table 4.1 Studies of leadership traits and characteristics Source: Adapted with permission from Northouse, PG. Leadership: Theory and Practice, 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2010 The trait approach is intuitively appealing as it is tempting to conceptualize leaders as possessing specific talents that enable them to take charge and motivate themselves and others to do extraordinary things. This model is applied by identifying, recruiting and installing people with the ‘right’ traits into positions of command. This approach was common in the military. However, the weakness with the trait approach lies in the weakness of trait theories as a model for understanding and predicting how people behave in general (for a review see, for example, Dweck, 2000). Traditionally, trait models described people’s behaviour without explaining how those patterns of behaviour develop in the first place or how they might change (Costa and McCrae, 1994; Goldberg, 1990; McCrae and John, 1992). Many trait theorists assume our traits are rooted in our biology and, as such, they assert that we cannot change very much (Costa and McCrae, 1994; Eysenck, 1982; Loehlin, 1992). Trait theories of leadership therefore assume you either possess the right traits for the job or you do not. Traits are assessed using self-report psychometric questionnaires whereby participants ‘identify’ their own patterns of behaviour, thought and emotion by rating themselves against the questions asked. Self-report questionnaires have been criticized, however, as a very inaccurate method of identifying an individual’s actual talents. Similarly, trying to determine another person’s traits over a short period of time (such as during an interview) has also proven to be inaccurate. Furthermore, it has been known for some time that the presence or absence of many of the key traits listed in Table 4.1 does not predict how effective a person will be as a leader across a range of situations (Stogdill, 1948). Few veterinary organizations within the UK currently use formal psychometric profiling techniques to identify and recruit staff in general, and leaders in particular. This has led to a lack of empirical data with respect to determining the usefulness of traits as a model for leadership within the profession. However, in the author’s experience, most veterinary employers rely heavily on their own evaluation of a colleague’s ‘attitudes and traits’ when they are deciding whether someone is suitable for a leadership role such as partnership. This is understandable; it is difficult to ignore your gut instinct when evaluating other people. Recent advances in psychology, however, are shedding light on how traits evolve and even change. Over the past few decades more and more psychologists have challenged the assumption that we are born with a set of predetermined traits. For example, a branch of psychology called attribution theory has demonstrated that the ‘mindsets’ which determine our behaviour are much more learned (i.e. acquired) than had been originally assumed. It has been shown that people learn different reasons (or attributions) why certain events turned out as they did. Seligman and Maier (1967) have demonstrated how people ‘learn to become helpless’ when they assume, erroneously, that their circumstances are beyond their control. This is the basis of Seligman’s theory of learned helplessness. While this theory and others like it (Dweck, 2000) were originally focused on resilience and well-being, the view that many of our key ‘traits’ are learned, as opposed to genetic, is also being applied to leadership (see below). As a result, most researchers no longer ask ‘Can leadership be learned?’ Rather, they are asking ‘How is leadership learned?’ In contrast to the traits approach, the skills approach focuses on a leader’s areas of competence as opposed to their personality. Katz’s (1955) ‘three-skill’ model represents the classic approach to the skills-based theory of leadership and management. According to Katz, effective management and leadership depend on three essential areas of competence: technical, human and conceptual. Katz asserts that the relative importance of each varies between different management levels. For example, lower (or supervisory) managers require mainly technical and human skill; middle managers require a significant component of all three, whereas upper management levels require higher levels of conceptual and human skill. In other words, the higher the leadership position, the greater the challenge of getting members of the group to work effectively together towards a common goal. Leaders therefore need increasing levels of ‘human’ and ‘conceptual’ competences to address this challenge as their level of leadership increases. A key premise of Katz’s model is that since skills are ‘learned’ behaviours leadership is open to anyone motivated enough to develop the breadth of skills that enables them to get people to work together towards desirable future goals. This view is in contrast to the Great Man and earlier trait models, which assume leaders are a select group fortunate enough to be born with the right characteristics.

Leadership and management in veterinary practice

Operators, managers and leaders

Theories on leadership

The trait approach

The skills approach

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine