CHAPTER 36 Lawsonia intracellularis

ETIOLOGY

Lawsonia intracellularis is the etiologic agent of the proliferative enteropathies of animals, variously known as proliferative enteritis, proliferative ileitis, and intestinal adenomatosis. This new bacterium, isolated and identified in the mid-1990s, is taxonomically distinct as a species.1,2 The obligate intracellular organism does not grow on conventional bacteriologic media but can be cultivated in some specific cell lines, including a rat small intestine cell line, under an atmosphere of reduced oxygen tension. Bacteria present in host or cultured cells are gram-negative, straight to slightly curved rods, 1.25 to 2 μm long and 0.25 to 0.43 μm wide. These organisms have a wavy, trilaminated outer cell wall, contain dense cytoplasmic granules, and divide transversely by septation.1

Isolates of intracellular bacteria from a variety of animal species affected with proliferative enteropathy (PE), including horses, show close 16S ribosomal deoxyribonucleic acid (rDNA) similarity (>98%) to cultures isolated from pigs, the species in which the disease is most prevalent.1

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Proliferative enteropathy attributable to infection with L. intracellularis has been described in a number of animal species, including the pig, hamster, fox, dog, ferret, rat, guinea pig, rabbit, monkey, ostrich, emu, sheep, deer, and horse.1 L. intracellularis has a worldwide distribution, and equine cases of PE have been reported in most American states3–7 and Canadian provinces8,9 and in Great Britain10 and Australia.11 Foals from the Czech Republic have been found to be fecal positive for L. intracellularis using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis.12 The source of infection has not been determined in equine cases. As with most other enteric microbial pathogens, fecal-oral spread and transmission through drinking water and food appear to be the common avenues for infection. Contact with pig manure is speculated to represent a potential source of infection for horses, but in most cases no history or evidence of direct exposure to pigs or their feces has been reported.

Because of the apparent wide host range of PE, numerous potential reservoirs likely exist. Recently, L. intracellularis was detected by PCR in the feces of a variety of animal species, including a red deer, red foxes, gray wolves, dogs, calves, hedgehogs, and a giraffe.13,14 Transmission of infection in foals may be through exposure to L. intracellularis–infected feces from feral animals or in-contact horses.8,11 Naturally occurring transspecies transmission of this disease has not been clearly documented, although experimental transmission from pig to hamster15 and from pig to foal16 has been reported with induction of disease. As observed in pigs, factors that may predispose foals to PE include weaning (age), overcrowding, lack of specific immunity, commingling of animals, and introduction of new animals on the premises.8

In pigs, infection and fecal shedding may persist as long as 12 weeks.17 L. intracellularis can survive for at least 2 weeks in the environment.18 The duration of bacterial shedding in feces of horses after infection has not been thoroughly determined. Similarly, the possible role of subclinical infections in the transmission of the disease between horses is not known. Subclinical PE occurs in pigs and rabbits.19

PATHOGENESIS

The severity of disease caused by infection with L. intracellularis depends on the number of organisms ingested by the host and the extent of host immunity.20 Intestinal flora and other enteric pathogens may facilitate the development of disease,2 and polymorphisms in equine immune response genes may predispose to L. intracellularis infection.12 The pathogenesis of PE is not totally understood, and most of the information available is extrapolated from experimental observations in hamsters and pigs and from infected cell cultures.1,2,21

After ingestion, bacteria associate with the cell membrane of dividing intestinal crypt cells and quickly enter the enterocyte through an entry vacuole. Approximately 3 hours later, bacteria are released from the endocytic vacuole and start to multiply free in the cytoplasm. Infected cells continue to divide, even when heavily infected. PE develops as a progressive proliferation of immature epithelial cells harboring numerous intracellular bacteria.1,2,21 The incubation period of the disease is 2 to 3 weeks in swine21 and is estimated to be the same in foals.16 Resolution of lesions is closely related to the disappearance of the intracellular bacteria.

Lesions of PE, when extensive, may potentially result in a significant decrease in intestinal digestive and absorptive capabilities causing diarrhea and weight loss. Hypoproteinemia is a common laboratory finding in foals affected with the disease.5–11 This low plasma protein concentration is probably attributable to the combined effect of intestinal protein loss, malabsorption of amino acids, and increased protein catabolism. In pigs with PE, evidence suggests that hypoproteinemia results from intestinal protein loss and malabsorption of amino acids; normal protein metabolism is observed after the resolution of digestive signs.22,23

CLINICAL FINDINGS

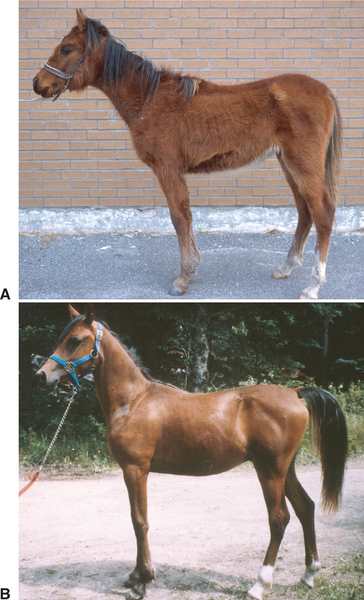

Most reports of PE in foals have described isolated cases,3–7,9,11 although multiple foals may be affected on breeding farms.8,10 The age of affected foals varies from 3 to 13 months, but weanling foals 4 to 7 months of age are most susceptible to L. intracellularis infection.8 There appears to be no gender or breed predisposition to the disease. Clinical signs are usually suggestive of the enteric location of the infection. Depression,3–6,8,9,11 fever,5,8,9,11 anorexia,3–6,8,9 weight loss,5,6,8,10,11 diarrhea, 3–6,8,10,11 and colic7,8 are often observed. Most of these clinical signs were also observed in a foal experimentally infected with a porcine isolate of L. intracellularis.16 Weight loss may become apparent over a few days, although one yearling was presented for growth retardation of 5 months’ duration.8 Extremely poor body condition with a rough haircoat and a pot-bellied appearance is common in severely affected foals (Fig. 36-1). Diarrhea may be of varying frequency and severity, ranging from soft “cow pie” feces to black and tarry or aqueous and profuse diarrhea.3,5,8 Similarly, colic signs, when present, are of variable severity.7,8 Subcutaneous edema may be marked, especially when fluid therapy is administered.6,8,9,11 However, severe hypoproteinemia may be present in absence of detectable subcutaneous edema (see following discussion). Concomitant disorders, such as upper or lower respiratory tract infection, intestinal parasitism, gastric ulcers, and dermatitis, were common findings in one study.8