53 Lameness

Ischaemia

INTRODUCTION

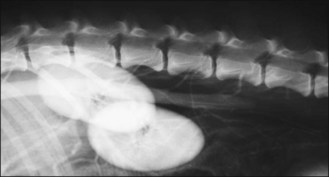

The dog featured in Figure 53.1 presented with a 24-hour history of shifting hindlimb lameness followed by an arched back and then sudden paraplegia on the day of referral. Femoral pulses were absent bilaterally but the hind paws were warm until they became cold 2 hours later. The right quadriceps femoris muscle was firm and were painful when touched as were the lumbar epaxial muscles. Pain perception and spinal reflexes were absent in both hind limbs. The cause was thought to be a hypercoagulable state from a protein-losing glomerulonephropathy. The dog was euthanized as the prognosis for long-term normality was guarded and the pain was extreme.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree