CHAPTER 27 Laboratory Diagnosis of Bacterial Infections

This chapter is designed to aid the veterinary clinician in collecting samples for bacterial culture, understanding the methods used to detect bacteria, interpreting results, and ensuring that optimal results are received from the microbiology laboratory.

DIRECT MICROSCOPIC EXAMINATION

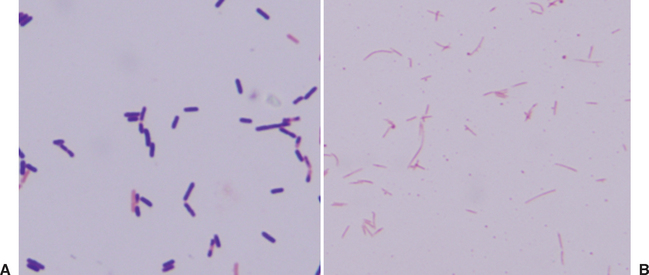

Every sample submitted for bacterial culture should receive a Gram stain to facilitate detection of bacteria. This methodology is rapid, is simple to perform, and can give vital information regarding the potential pathogens present. Examination of the Gram-stained specimen can indicate the relative number of bacteria present. The Gram reaction, either gram positive or gram negative, and bacterial morphology can be used to develop a list of possible etiologies that can be used for empiric antimicrobial drug selection (Table 27-1). The observation of bacteria with specific morphologic and staining characteristics is consistent with the presence of anaerobic bacteria and indicates that the sample should also be incubated anaerobically (Fig. 27-1). For example, observation of large, gram-positive rods or long, tapered gram-negative rods suggests Clostridium spp. or Fusobacterium spp. infection, respectively. Failure to observe bacteria on a Gram stain does not rule out an infection because bacteria need to be present in fairly high numbers, 104 to 106/mL, to be detected.

Table 27-1 Gram Stain Reaction and Morphology of Common Bacterial Pathogens of Horses

| PATHOGEN | MORPHOLOGY |

|---|---|

| Gram-Positive Organisms | |

| Streptococcus equi subsp. equi | Cocci, often in long chains |

| Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus | Cocci, often in short chains |

| Rhodococcus equi | Pleomorphic coccobacilli |

| Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis | Pleomorphic coccobacilli, diphtheroid |

| Dermatophilus congolensis | Cocci, “railroad track” |

| Actinomyces spp. | Rods, coccobacilli to filamentous and branching |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Cocci |

| Clostridium difficile | Rods |

| Gram-Negative Organisms | |

| Escherichia coli | Rod |

| Klebsiella spp. | Rod |

| Actinobacillus spp. | Rod |

| Pasteurella spp. | Rod |

| Salmonella spp. | Rod |

| Pseudomonas spp. | Rod |

| Leptospira spp. | Curved rods |

| Bacteroides spp. | Rod |

| Fusobacterium necrophorum | Rods, tapered ends |

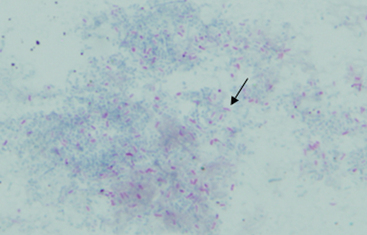

Acid-fast (Ziehl-Neelsen) or modified acid-fast (Kinyoun) stains can be used to help identify members of the nocardioform-actinomycete group of bacteria, including Mycobacterium spp. (acid fast), Rhodococcus equi (weakly acid fast), and Nocardia spp. (weakly acid fast). Bacteria that are acid fast retain the stain carbolfuchsin and appear bright pink because of the waxy outer membrane containing mycolic acid (Fig. 27-2).

SAMPLING FOR BACTERIAL CULTURE

Indications

Clinical signs suggestive of, but not pathognomonic for, bacterial infections include fever, pain, and swelling. Clinicopathologic findings consistent with a bacterial infection include increased white blood cell (WBC) count with a neutrophilia and possibly a left shift, increased plasma fibrinogen and other acute-phase protein concentrations, and hyperglobulinemia. All these findings are unlikely to be present, and their absence does not rule out the possibility of infectious disease. Cytologic examination of fluid or cells collected from the site of a suspected infection generally reveals neutrophilic inflammation and in some cases a granulomatous or pyogranulomatous response. Degenerate neutrophils are a strong indication that a septic process is present, and bacterial culture should always be performed.

Samples Most Appropriate for Culture

Ideally, specimens from sites that are normally sterile, such as joint fluid, peritoneal fluid, and blood, are the best samples to collect for culture because any bacteria isolated are likely causative. Culture of clinical samples obtained from sites that are colonized with bacterial flora, such as nasal or oral mucous membranes, will usually yield normal bacterial flora of that region (Box 27-1). This may result in spending the client’s money and expending the laboratory’s efforts needlessly to identify many nonpathogenic bacteria. Because many of these bacteria can also be opportunistic pathogens, it is difficult to determine if they are causing the clinical condition. For example, collection of purulent discharge from the nasal passage of a horse will certainly yield bacteria that are potentially pathogenic, such as Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus, but their detection does not mean this bacterium is the cause of the discharge. It is preferable to identify the specific site of infection, such as sinus, guttural pouch, or lung, and collect the sample for culture from that location.

Box 27-1 Common Normal Bacterial Flora of Horses for Selected Sites

Oral and Nasal Cavities and Pharynx

Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus

Streptococcus spp. (nonhemolytic or α-hemolytic)

Several exceptions to this rule can be made. In general, if the clinician is trying to detect a pathogen not present in colonized sites in clinically normal animals, the laboratory can specifically target identification efforts toward that organism or use selective media to enhance pathogen detection. Detection of Streptococcus equi subsp. equi from a nasal or pharyngeal swab would be appropriate because the microbiology laboratory can focus on β-hemolytic streptococcal isolates for definitive identification. Box 27-2 provides a list of specimens to be collected for bacterial culture of different body systems.

Box 27-2 Samples and Tissues to Select for Common Conditions and Diseases of Major Organ Systems

Methods for Collection

Tissue (collected as an aspirate or biopsy) and fluids are the best samples to collect for bacterial isolation. In general, larger samples increase the likelihood that a causative pathogen will be isolated because the sample can be centrifuged to concentrate any bacteria. Samples should be collected as aseptically as possible and placed in a sterile container. Submission of samples in a syringe is acceptable, but the needle should be removed and the syringe capped to avoid inadvertent injury and introduction of bacteria to personnel. Swabs are not the best choice for sampling because they hold only a small amount of material, and some swabs are made of substances that inhibit bacterial growth. Occasionally, however, a swab will be the only choice for sampling. Swabs are often not appropriate for fecal or intestinal cultures because of their inadequate sample volume. It is best to submit multiple samples in individual containers to eliminate the possibility of cross-contamination.

Suspected Anaerobic Infection

The clinician should decide before submission whether anaerobic culture is necessary so that the sample can be handled appropriately (see Chapters 44, 45, and 48). For example, when emphysema is detected within a tissue, such as in necrotizing myositis, anaerobic culture would be indicated. Likewise, anaerobic infections are common in abscesses, pneumonia, and pleuritis of horses. Anaerobic culture of tissues from an animal that has been dead for many hours may not be worthwhile because anaerobes will proliferate and disperse throughout the carcass. For example, observation of gram-positive rods typical of Clostridium spp. in muscle in a 24-hour-old carcass would not be indicative of clostridial myonecrosis.

Many anaerobes are highly sensitive to oxygen and will die during transport if not protected appropriately. Therefore, they should be stored and transported in an environment that minimizes their exposure to the atmosphere. Tissues or a generous volume of fluid (several milliliters) are the best samples for anaerobic culture. If a swab must be used for an anaerobic culture, it should be placed in a semisolid transport medium, such as anaerobic transport media or Port-a-Cul (BD Diagnostic Systems), to minimize air exposure. Tissues should be at least 1 × 1 cm. If very small tissue or fluid samples are available for sampling, they should be placed in transport media as well. Aerobic swabs are unacceptable for anaerobic culture and will not be set. Even anaerobic swabs poorly support anaerobic organisms and should only be used for short-term (a few hours) transport to the laboratory. Similarly, liquid should be placed on top of the transport media and pushed down into the gel to preserve the anaerobic environment.

Blood Culture

Neonatal foals are the equine patients at greatest risk for septicemia or bacteremia (see Chapter 6). However, blood culture may also be considered in older foals and adults when bacteremia or septicemia is suspected. Many systems are available for culturing blood, including conventional broth-based, biphasic broth-based, and lysis-concentration/filtration methodologies.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree