Radiography of joints: technique and interpretation39

2.1. RADIOGRAPHY OF JOINTS: TECHNIQUE AND INTERPRETATION

Technique

Arthrography (negative, positive, double contrast)

Indications

Preparation

Technique (shoulder)

Technical errors on arthrography

Interpretation of joint radiographs

2.2. SOFT TISSUE CHANGES ASSOCIATED WITH JOINTS

Soft tissue swelling

Gas in joints

2.3. ALTERED WIDTH OF JOINT SPACE

Decreased joint space width

Increased joint space width

Asymmetric joint space width

2.4. OSTEOLYTIC (EROSIVE) JOINT DISEASE

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Joints

2.2 Soft tissue changes associated with joints41

2.3 Altered width of joint space42

2.4 Osteolytic (erosive) joint disease42

2.5 Proliferative joint disease44

2.6 Mixed osteolytic–proliferative joint disease45

2.7 Conditions that may affect more than one joint45

2.8 Mineralization in or near joints46

Lesions in joints may be radiographically subtle, and so attention to good radiographic technique is essential.

1. Highest definition film–screen combination consistent with the thickness of the area or appropriate digital radiography algorithm.

2. No grid is necessary except for the shoulder and hip joints in large dogs.

3. Accurate positioning and centring, with a small object–film distance to minimize geometric distortion and blurring due to the penumbra effect.

4. Straight radiographs in two planes are usually required (i.e. orthogonal views), with oblique views as necessary.

5. Close collimation to enhance radiographic definition by minimizing scatter, and for radiation safety.

6. Correct exposure factors to allow examination of soft tissues as well as bone.

7. Beware of hair coat debris creating artefactual shadows.

8. Radiograph the opposite joint for comparison if necessary.

9. Use of stressed views (traction, rotation, sheer, hyperextension/flexion and fulcrum-assisted) and weight-bearing or simulated weight-bearing views for the detection of subluxation and altered joint width – great care with radiation safety is needed if the patient is manually restrained. The vacuum phenomenon may occur with traction views of the shoulder, hip and spine (see 2.2.13).

10. For analogue film, ensure good processing technique to optimize contrast and definition.

Detection of the extent of the joint capsule or of rupture of the joint capsule; examination of the bicipital tendon sheath (shoulder joint); assessment of cartilage thickness and flap formation; detection of synovial masses and intra-articular filling defects such as radiolucent joint ‘mice’; to see if a mineralized body is intra-articular. Most often performed in the shoulder joint.

General anaesthesia; survey radiographs; sterile preparation of the injection site.

Insert a 20- to 22-gauge short-bevel needle 1 cm distal to the acromion and direct it caudally, distally and medially into the joint space. Joint fluid may flow freely or require aspiration; obtain a sample for laboratory analysis.

• Positive contrast arthrogram – inject 2–7 mL of 100–150 mg I/mL isotonic iodinated contrast medium (e.g. a non-ionic medium such as iohexol) depending on the patient size, withdraw the needle and apply pressure to the injection site; manipulate the joint gently to ensure even contrast medium distribution; take mediolateral, caudocranial and cranioproximal–craniodistal (skyline) radiographs. Use lower volumes for assessment of the joint space only and higher volumes for the biceps tendon sheath.

• Negative contrast arthrogram – use air.

• Double-contrast arthrogram – use a small volume of positive contrast medium followed by air.

Contrast medium not entering the joint space but injected into surrounding soft tissues; insufficient or too much contrast medium used; gas bubbles mimicking radiolucent joint mice.

1. Use optimum viewing conditions – for analogue films a darkened room, bright light and dimmer facility, magnifying glass, glare around periphery of film masked off.

2. With digital images, manipulation of greyscale and size is readily performed but beware of digital artefacts.

3. Compare with the contralateral joint and use radiographic atlases and bone specimens.

4. Consider patient signalment and associated clinical and laboratory findings.

Assess the following.

5. Number of joints affected (e.g. single – trauma, sepsis or neoplasia; bilateral – osteochondrosis, bilateral trauma; multiple – systemic or immune-mediated disease).

6. Alignment of bones forming the joint; examine bones and joints proximally and distally.

7. Epiphyseal shape and joint space congruity.

8. Joint space width (changes reliable only if severe or if weight-bearing views obtained).

9. Articular surface contour – remodelling, erosion.

10. Subchondral bone opacity – sclerosis, erosion, cyst formation, osteopenia.

11. Joint space opacity – gas, fat, mineralization, foreign material.

13. Soft tissue changes (may be more obvious radiographically than clinically).

a. Increased soft tissue – concept of ‘synovial mass’, as synovial tissue and synovial fluid cannot be differentiated on survey radiographs.

b. Reduced soft tissue – muscle wastage due to disuse (especially in the thighs).

14. Other articular and periarticular changes.

a. Intra- and periarticular mineralization (see 2.8).

b. Joint mice (apparently loose, mineralized articular bodies, although they may in fact be attached to soft tissue).

c. Intra-articular fat pads reduced by synovial effusion.

d. Fascial planes and sesamoids displaced by effusions and soft tissue swelling.

e. Periarticular chip and avulsion fractures.

f. Periarticular osteolysis.

g. Periarticular new bone other than due to osteoarthrosis.

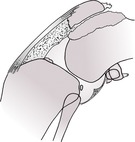

Differentiation between joint effusion and surrounding soft tissue swelling may not be possible except in the stifle joint, but both are often present. A joint effusion will compress or displace any intra-articular fat and adjacent fascial planes and is limited in extent by the joint capsule; the effusion may be visible only when the radiograph is examined using a bright light. Periarticular swelling may be more extensive and will obliterate fascial planes. Occasionally, arthrography may reveal soft tissue pathology even when survey radiographs are normal, for example in synovial sarcoma or villonodular synovitis.

1. Joint effusion or soft tissue swelling (Fig. 2.1).

a. External trauma.

b. Damage to an intra-articular structure such as a cruciate ligament or meniscus.

c. Early osteochondrosis confined to cartilage; medial coronoid disease.

d. Early septic arthritis.

e. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) – usually multiple joints, symmetrical.

g. Ehrlichiosis*.

h. Lyme disease* (Borrelia burgdorferi infection).

i. Polyarthritis–polymyositis syndrome, especially Spaniel breeds.

j. Polyarthritis–meningitis syndrome – Weimaraner, German Short-haired Pointer, Boxer, Bernese Mountain dog, Japanese Akita, also cats.

k. Heritable polyarthritis of the adolescent Japanese Akita.

l. Polyarteritis nodosa – stiff Beagle disease.

m. Drug-induced polyarthritis, especially certain antibiotics (e.g. fluoroquinolones such as enrofloxacin).

n. Immune-mediated vaccine reactions.

o. Other idiopathic polyarthritides.

p. Chinese Shar Pei fever syndrome – short-lived episodes of acute pyrexia and lameness with mono- or pauciarticular joint pain and swelling of the tarsi and carpi; occasionally enthesiopathies.

2. Recent haemarthrosis.

a. Trauma.

b. Coagulopathy.

3. Joint capsule thickening.

4. Periarticular oedema, haematoma, cellulitis, abscess, fibrosis.

5. Soft tissue tumour.

6. Synovial cysts – herniation of joint capsule, bursa or tendon sheath. Infrequent, and usually associated with degenerative joint changes. In cats, described only at the elbow.

7. Soft tissue callus – large dogs, especially elbows.

8. Villonodular synovitis – often bone erosion at the chondrosynovial junction too.

9. Cats – various erosive and non-erosive feline polyarthritides; the latter showing soft tissue swelling only.

10. Fat mistaken for gas.

11. Superimposed skin defect.

12. Post arthrocentesis.

13. Vacuum phenomenon – seen in humans in joints under traction, when gas (mainly nitrogen) diffuses out from extracellular fluid. In dogs, reported only in the shoulder, hip, intervertebral disc spaces and intersternebral or sternocostal spaces and only in the presence of joint disease (e.g. shoulder osteochondrosis, degenerative joint disease and chronic disc disease).

14. Open wound communicating with the joint.

15. Infection with gas-producing bacteria.

2. Artefactual – flexed joint in craniocaudal or caudocranial view.

3. Articular cartilage erosion due to severe, chronic degenerative joint disease.

5. Periarticular fibrosis.

6. Advanced septic arthritis with erosion of articular cartilage and collapse of subchondral bone (see 2.4.6 and Fig. 2.3).

7. Cats – arthropathy is seen in some cases of acromegaly (growth hormone-secreting pituitary tumour). Cartilage hypertrophy and hyperplasia lead to osteoarthrosis. In early cases, the joint space may be widened due to cartilage thickening, but in later stages the joint space collapses.

8. Traction during radiography.

9. Skeletal immaturity and incomplete epiphyseal ossification.

10. Severe joint effusion.

11. Recent haemarthrosis.

12. Subluxation.

13. Intra-articular soft tissue mass.

14. Intra-articular pathology causing subchondral osteolysis (e.g. osteochondrosis, septic arthritis, soft tissue tumour, rheumatoid arthritis).

16. Cats – early acromegalic arthropathy (see above).

17. Normal variant in some joints, dependent on positioning (e.g. caudocranial views of the shoulder and stifle).

18. Congenital subluxation or dysplasia.

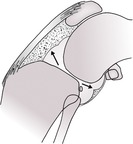

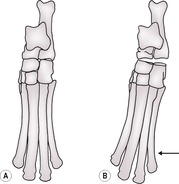

19. Collateral ligament rupture (Fig. 2.2) – stressed views may be required to demonstrate subluxation.

20. Asymmetric narrowing or widening of the joint space due to other pathology – see above.

1. Apparent osteolysis due to incomplete epiphyseal ossification in the young animal.

3. Artefactual in cases of severe osteoarthrosis, when superimposition of irregular amounts of new bone creates areas of relative lucency, mimicking osteolysis. Diagnosis of neoplasia or sepsis superimposed over osteoarthrosis may be very difficult radiographically.