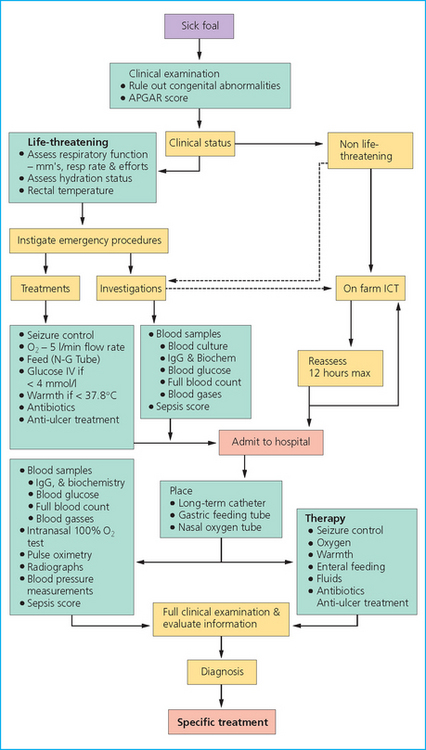

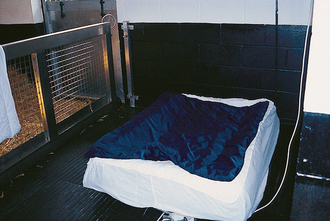

Chapter 8 The neonatal period is characterized by dramatic changes in many physiological events in the foal. The normal foal is a very precocious animal – within an hour of birth it will usually be standing and feeding effectively. The transition from intrauterine life to independence is made very quickly with dramatic changes in the vital signs and behavior (see p. 1). Major dynamic alterations are taking place and any of these can go awry. Many events that would have no material effect on an adult horse can be of critical importance to the foal. The foal cannot therefore simply be regarded as a small horse. From a clinical perspective there are effectively two main types of sick foal: • Type 1: foals that are abnormal from birth – for example, cases that do not rise and suckle within 3 hours. • Type 2: foals that are normal at birth and develop abnormal signs within the first 3 days (e.g. depression, change in behavior, seizures, etc.). Type 2 foals (i.e. those that become ill after birth and normal feeding have taken place) have a better prognosis and often require less intensive care. Many foals appear to be in reasonable condition but have predisposing conditions that originate before birth or during the birth process. It is often said that a sick foal often looks its best at 12–24 hours although whether the foal is normal is another matter entirely. Although many of the foals that survive treatment in neonatal intensive care units are still small as yearlings they are largely able to correct this by the 2-year-old stage and long-term performance studies suggest that they can achieve normal athletic performance. Therefore the expense and effort required to save the foal is worth it although the outcome will depend heavily on the quality of the care provided. Half-measure care is unlikely to be good enough. Nevertheless there are still some foals that benefit from a milder degree of short-term intensive care input – if only to lift them into a better metabolic state until they adjust to their new circumstances or until therapy is applied to correct a specific problem. There are defined risk factors that can be identified prepartum or at the time of the birth. These allow pre-emptive decisions on the part of the clinician who may suspect that a foal is ill (see p. 60). Often clinically significant signs are detected during what is otherwise a routine check (see p. 75) and so the clinician will need to be properly prepared for any eventuality. Disease often progresses rapidly in foals and delays while treatment is obtained can be very harmful; a delay of 2–3 hours can change the prognosis from fair to hopeless. Detection of an abnormal foal should immediately trigger a chain of investigation and management that is conducive to the foal’s survival. ‘The medical screening of patients to determine their relative priority.’ The objective of a good history and performing a clinical examination is to establish: • a list of all the identifiable problems present • a differential diagnosis list • a diagnosis or likely diagnosis • a logical treatment plan to maximize the chances of a full recovery (including immediate stabilization medication) • whether to leave the foal at the farm, admit it to the clinic or refer (see p. 455) • whether further diagnostic tests are needed to eliminate some of the differential diagnoses or whether to monitor response to treatment The initial assessment of the critically ill foal is usually limited to cardiorespiratory parameters (pulse and respiratory rate/quality, mucous membrane color) and the body temperature and mental status (demeanor and state of consciousness). Treatment at this stage is usually symptomatic (i.e. each prominent symptom is dealt with directly). Once the foal has been stabilized a detailed investigation may permit a definitive diagnosis and then specific treatment can be given. A logical triage approach is shown in Figure 8.1. For further details on clinical examination of the foal see page 82. In order to maintain a full intensive care program you will need to have three nurses and two veterinary surgeons available at all times. At least two lay personnel will be needed in addition. Intensive care needs someone in attendance at all times (and often actually sitting with the foal) (Fig. 8.2) to ensure temperature maintenance, catheter and nasal/gastric tube placement and suitable feeding regimens. Remember that the mare will also need looking after. Contact between the mare and foal may be needed or may not be allowed so a mobile division is required (Fig. 8.3). Some mares can become aggressive towards people when they appear to be permanently interfering with their foals. A mare that will not settle should be placed on the other side of a barrier (rather than removing her to another stall). Visual and olfactory contact must be possible at all times between mare and foal. Prolonged separation is harmful to both. Foals with their dams should be bedded on clean straw rather than shavings or paper, which get into the eyes, nose and mouth (and can cause problems if swallowed because they are not digestible and effectively ‘clog’ up the stomach, causing non-responsive colic). This is particularly important because sick foals spend a significantly longer time lying down with their noses in the bedding compared with healthy foals (Fig. 8.4). Critical foals should be slightly elevated from the ground, for example on a heated waterbed or mattress with a readily cleanable surface (preferably within sight of the mare). Ideally the mattress should be contoured so that urine runs away from the foal. Warm, dry, clean blankets should be used underneath the foal as well as on top of it. • laboratory facilities for rapid (accurate) results (i.e. hematology, blood gas and electrolyte monitors) • blood pressure monitor, pulse oximetry • ECG with ‘stick-on’ electrodes (not clips) • full washing facilities with hot/cold running water, refrigerator, freezer (for plasma/colostrum/milk), microwave oven • accurate scales capable of weighing the foal* • stomach tubes, feeding tubes, nasal oxygen tubes and endotracheal tubes • blankets and ‘vet beds’/bandages/leg wraps and wound dressings • normal saline/Hartman’s solution • alarms and telephone numbers. • stethoscope, thermometers, scissors • clippers/scrub and spirit for skin sterilization • heparin saline for catheter irrigation • blood collection tubes/needles, syringes Three levels of critical care have been described: • seizure control – with anticonvulsants, corticosteroids, etc. • nutritional requirements – IgG and other requirements • hydration/fluid and electrolyte requirements (including circulatory support) • sepsis assessment/antibiotics Seizures must be controlled immediately. The following can be used: • Diazepam: this is useful in emergency situations but has only a short duration of action. The initial dose is 5–10 mg/50 kg (0.05–0.2 mg/kg) i.v. every 30 minutes as required. Usually 5 mg increments are administered to effect and to a maximum of 40 mg total. • Detomidine (and butorphanol): this is a α2-adrenoreceptor agonist which reduces the discharge rate of central and peripheral neurons, and decreases the CNS sympathetic output. A dose rate of 0.01 mg/kg i.v. is usually used (combined with 0.02 mg/kg butorphanol). • Phenytoin: this acts by diminishing the spread and propagation of focal neural discharges. It has a relatively short half-life in the horse. A loading dose of 5–10 mg/kg i.v. can be given initially followed by a maintenance dose of 1–5 mg/kg i.v. q 6 hours. This is a useful drug in practice (many foals maintain their suck reflex) and it can be used orally for longer-term therapy. • Phenobarbitone: this reduces the excitability of the CNS. An initial loading dose of 10–20 mg/kg diluted in 30 mL sterile water is used over 20 minutes. In some compromised foals the duration of action is considerably prolonged. The maintenance dose is 5–10 mg/kg either i.v. or p.o. q 8–12 hours. The maintenance dose rather than a loading dose may control the foal. The dose should gradually be tailed off. It should not be used in combination with phenytoin or cimetidine. • Pentobarbitone: this produces cardiorespiratory depression. A dose rate of 2–10 mg/kg i.v. is recommended but it is wise to start at the lower end of the range and increase as necessary. It can be repeated every 3–6 hours if needed. Cerebral edema can be controlled by the following agents: • Corticosteroids: their use in seizure control is controversial. Dexamethasone is used at a dose of 4 mg/50 kg foal q 12 hours i.v. or i.m. Methylprednisolone at 1–2 mg/kg i.v. can be used, or there have been reports of clinicians using a single high dose of 30 mg/kg i.v. – both are recommended within 6 hours of injury. • DMSO: this acts as a cell protectant and diuretic, and has mild anti-inflammatory effects. It is given at a dose of 0.5 g/kg in 500 saline over 20 minutes. • Mannitol: this is given at a dose rate of 0.25 g/kg as a 20% solution over 15–40 minutes i.v. (but be careful of hemolysis). It is contraindicated if CNS hemorrhage is suspected. • Vitamin C: this is given at an arbitrary dose of 1000 mg total dose/50 kg foal i.v. q 12 hours. It is very important to establish the state of asphyxia early on with the following: • clinical examination – heart rate, pulse quality and mucous membrane color, respiratory rate Sick foals and especially those with cardiopulmonary problems should be maintained in sternal recumbency as much as possible (Fig. 8.5). In any case even if sternal recumbency can be maintained the foal should be turned regularly (every 1, possibly 2, hours). Often the disturbance to the foal is less significant than loss of lung function, but if the foal finds it too stressful then do not fight it! Even sick foals will usually tolerate oxygen levels of 50–60 mmHg provided that the PCO2 is normal. However, if blood oxygen tension falls below 50 mmHg then oxygen administration is obligatory. Because of the lack of available blood gas machines in many practices, pulse oximetry can be used as an indicator of the need for oxygen. Oxygen can be given by intranasal tube (see p. 385) or by intratracheal tube (via either the nasal route or transcutaneously). In most cases, nasal or tracheal oxygen administration is a valuable procedure at the outset. Typically foals require support for 2–4 days, although some may require oxygen for longer. If the foal is both hypoxic and hypercapnic (PaCO2 over 50 mmHg) it can be assumed that the foal is not ventilating adequately and, although the cause can be due to central nervous depression or problems at the alveolus (pneumonia/surfactant deficits), artificial ventilation should be considered. This is not undertaken lightly because there are serious problems both with the procedure and with postventilation complications, but it should also not be delayed unnecessarily. Artificial ventilation requires a moribund or sedated/anesthetized foal (see p. 423). 1. Ensure sternal recumbency and check that the airway is clear (with possibly suction of airway secretions) – turn hourly if possible, encouraging/holding the foal to stand for 5 minutes each time. 2. Administer oxygen if there is: b. respiratory rate < 30, or > 80, or obvious distress c. pale or cyanotic color to the mucous membranes e. hypercapnia (CO2 > 65 mmHg). 3. Methods of administering oxygen include: a. Intranasal: give 3–10 L/min of 100% (see p. 385). b. Facemask (but this can be uncomfortable and may occlude a nostril – see p. 444). i. Once in place an adequate tidal volume should be achieved. If an open airway does not re-establish effective ventilation in the face of vigorous patient attempts, the position of the tube should be checked and the lungs auscultated and percussed to eliminate the possibility of a pleural space disorder or severe parenchymal lung disease. ii. A Bain circuit or AMBU bag with line attached should be connected to the endotracheal tube. iii. The oxygen supply should be connected to the Bain tubing or AMBU bag via a flow regulator and a 2-liter reservoir bag should be used. iv. The flow rate should be set at 10 L/min as a minimum. Lower flow rates are inadequate for Bain tubing circuits or in foals 50 kg or more. v. Manual intermittent positive pressure at a rate of 20–30/min is then instigated. The volume delivered is approximately 500 mL/breath. This is reflected in only a slight chest expansion; excessive pressure should be avoided (no more than 20–30 cm H2O should be used). Vigorous ventilation may cause serious lung damage. vi. Periodically check for spontaneous respiration and, once movement of air has been established, re-evaluate the adequacy of oxygenation. 4. Respiratory stimulation: if there is hypercapnia then give either: a. doxapram drip (but not recommended in the immediate postpartum period, see p. 71) b. caffeine – 10 mg/kg p.o. loading dose then 2.5 mg/kg/day p.o. (but beware of an increase in heart rate and neurological/hyperesthetic signs). 5. Bronchodilators such as theophylline, aminophylline, terbutaline and ipratropium have been used in some cases, but their efficacy is still controversial. 6. If the foal is hypoxic (PaO2 < 50–60 mmHg) and the PaCO2 is over 40 mmHg and rising, artificial ventilation should be considered but the procedure is difficult and specialized. It requires a sedated or moribund foal and very careful use because there are major dangers both during and after the procedure (see p. 423). 7. Surfactant administration has been given to foals in practice at varying dose rates and various administration routes (e.g. transtracheal, via an endotracheal tube) following guidelines used in human infants. However, it is extremely expensive to buy and it has not been possible to assess its efficacy. Although normal foals have a remarkable ability to maintain their body temperature, sick foals rapidly become hypothermic. This may be exacerbated by central nervous depression and sepsis. Rectal temperature will usually be low except in acute stages of infections. Hypothermia is a major reason for both depression and death and the survival of the foal will depend on how effectively and carefully the temperature is restored. Attempts to raise the body temperature quickly almost always fail – peripheral vasodilatation in the skin is actually the last thing the foal needs! Slow raising of the core temperature is the best method and this involves both provision of warm intravenous fluids and prevention of heat loss by blankets and leg wraps (Figs 8.6, 8.7).

INTENSIVE CARE, THERAPEUTICS AND NURSING

INTRODUCTION

INITIAL EVALUATION OF THE SICK NEONATE

TRIAGE

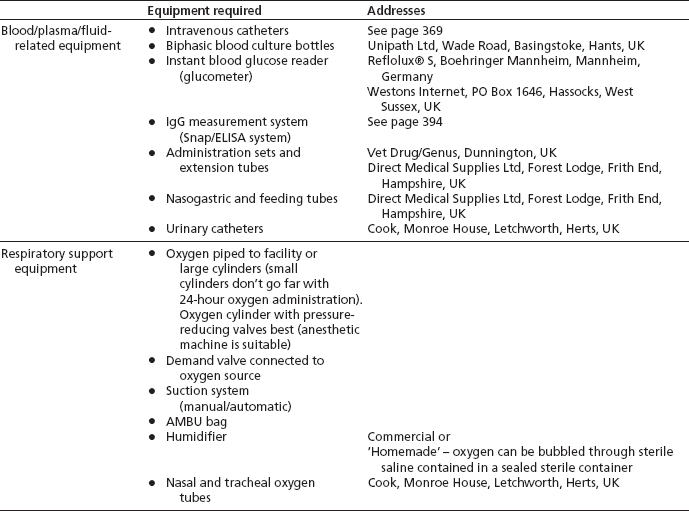

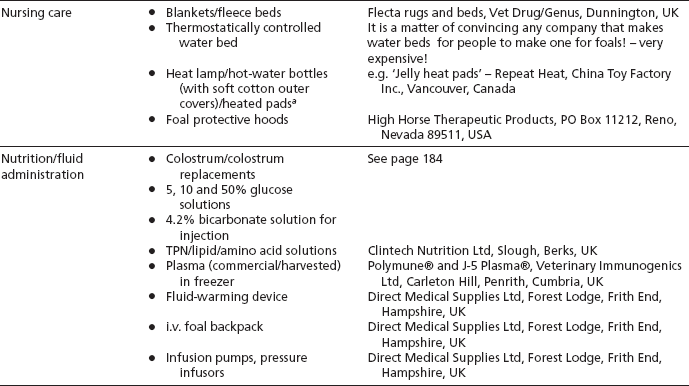

EQUIPMENT REQUIRED FOR A FOAL INTENSIVE CARE UNIT

STAFF (24 HOUR) IS ESSENTIAL

BASIC REQUIREMENTS

Stabling

Bedding

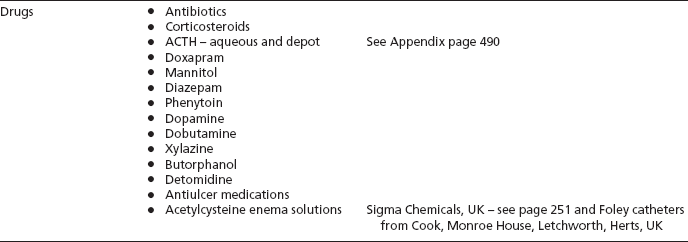

General equipment

CRITICAL CARE

Specific critical care therapy

SPECIFIC CRITICAL CARE THERAPY

Seizure control

Action

Respiratory support

Action

Warmth