10 Injuries Associated with Physical Agents

Hyperthermia/heat stroke

Heat stroke is a result of exposure to a hot environment where the normal physiological mechanisms, used to maintain the core body temperature within defined limits, are overwhelmed and the animal is unable to prevent its body heat rising to harmful and frequently fatal levels. Considerable investigation of the pathophysiology and circumstances predisposing to heat stroke has been undertaken.1–8 The typical heatstroke patient is usually collapsed, has a very high body temperature, and shows serious complications in the brain, kidney, liver and circulation. Veterinarians may be asked to examine a variety of animals affected by heat stroke, including horses, cattle and pigs, but dogs appear to be the subject of forensic investigations more commonly than other species.

This type of scenario can readily occur inside a vehicle in summer. As the temperature rises in the vehicle, the dog pants to cool down but the fluid lost via evaporation from the mouth causes the relative humidity to rise inside the vehicle. The dog’s body temperature rises and the dog becomes restless, thereby increasing heat generation in the muscles and putting further strain on the already overburdened heat regulatory mechanisms. If ventilation in the vehicle is insufficient to remove the water-laden air from around the dog in the vehicle, the situation deteriorates progressively. The time taken to develop clinical and pathological features of heat stroke/hyperthermia is variable depending on the environmental conditions (ambient temperature, humidity, ventilation) and to some extent on the coping mechanisms of the individual dog. It may range from less than an hour in extreme cases to several hours in less severe circumstances (Case study 10.1, Fig. 10.1).

Case study 10.1

Two adult black Labrador dogs were confined in a vehicle in full sun on a hot summer’s afternoon. The windows were left open approximately 2–3 inches (5–7 cm). About 2.5 hours later, one dog was found dead (Fig. 10.1) and the other in deep distress. Fully developed rigor mortis was demonstrated by the attending veterinarian 50 minutes after the vehicle was opened, but may have been present earlier.

Fig. 10.1 This Labrador dog died from hyperthermia after being left in a motor vehicle (see Case study 10.1). Note blood-stained fluid on the table under the chin. This has leaked from the mouth and nose.

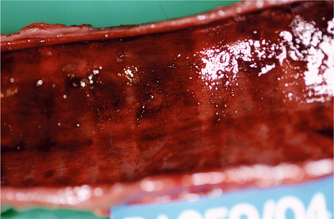

All organs (including the mucous membranes, which may be discoloured deeply red or dirty brown) are affected by vascular congestion. This change is most pronounced in the trachea (Fig. 10.2), lungs and bronchi. The heart, kidneys, meninges, lymph nodes and muscles may also show severe congestion.9

The speed of onset of rigor mortis is increased by high environmental and body temperatures and muscular effort.10 For all of these reasons, the onset of rigor mortis in dogs that die from heat stroke can be extremely rapid. The rate of post-mortem changes is also accelerated in hyperthermic animals.

Frostbite

In small animals, the ears, digits, scrotum and tip of tail are the areas most commonly affected because of their peripheral position, lack of hair or limited blood supply.11 The hind feet of calves are vulnerable, together with the tips of the ears and the distal 5–10 cm of the tail. Calves that are unwell as a consequence of pneumonia, diarrhoea or other systemic infections are at greater risk than healthy calves.12,13 Adult cattle may develop frostbite of the teats, base of udder and scrotum.

Frozen areas may develop a dark or bluish appearance with diffuse subcutaneous oedema and haemorrhage. Ischaemic necrosis may lead to sloughing, but the extent of the damage may not be fully demarcated until 4–15 days after the incident.14,15

Frostbite in birds is not uncommon16 and usually affects the feet, although distal wing necrosis of falcons may also be a cold-related injury.17 In addition to lack of acclimatisation of non-native birds, various risk factors include unseasonable weather, anaesthesia, wire cages, metal leg bands and any constrictions to blood supply, such as over-tight bandaging or previous injury. The scaly legs of birds do not blister, as might be seen in mammals, but oedema of the foot or lower limb may be noted after 24 hours. It may take 3–6 weeks before demarcation of viable and dead tissue can be appreciated visually.

Electrocution

Injuries caused by electricity range from electrothermal burns through fractures, cardiac and neurological damage, vascular and other tissue damage to death. Considerable information is available on the mechanisms, immediate effects, long-term deficits and causes of death in humans.18 The nature of the injuries caused by the passage of the current is governed by the physics related to the flow of the electrical charge. Therefore, many of the observations made on people may be directly applicable to domestic animals. However, some differences related to posture and gait are clearly present.

Electrothermal burns

Wildlife can suffer very severe burns when they contact high-voltage electricity cables. Prolonged (seconds) contact causes full-thickness skin burns and destruction of underlying tissues including muscle, tendons and bone (Fig. 10.3). The skin at the margins of the burns may be carbonised and the surrounding skin or feathers may be coated with soft, brown crumbly material, which is the remnant of heated blood/tissue (Fig. 10.4). Severe burning may also happen when indirect contact is established in the form of an electrical arc between two objects of differing potential. The temperature of an electrical arc is around 2500°C and causes deep burns at the point of contact.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree