10 Infectious Disease Scenarios

TRAVEL AND ANIMAL CONTACT

The U.S. Department of Commerce estimates that at least 30 to 40 million Americans visit other countries each year.1 Some of these travelers contract diseases while overseas and may return home still symptomatic. Some of these travel-related diseases are zoonoses resulting from contact with domestic or wild animals.

Many international travelers restrict their stays to hotels in urban or other well-developed areas that involve reduced risk of animal contact. Yet the growing popularity of ecotourism, religious pilgrimages, wildlife safaris, and other forms of adventure travel may increase the chances of travelers contracting an animal-related infectious disease during their trips. Animal contacts are possible even in cities and elsewhere on the beaten path; for example, high levels of pet allergens have been found in vacation hotels in some countries.1

Animal travel across borders is increasing as well. In 2006, more than 287,000 dogs were estimated to have entered the United States from foreign countries (including Mexico and Canada), 25% of which were unvaccinated.2 Many of these dogs were imports, accompanying their owners. The increasing popularity of traveling with one’s pet may result in a wide range of exposure risks for both the pet and owner. In addition, some individuals may acquire a pet overseas and return home with it.

Key Points for Clinicians and Public Health Professionals

Public Health Professionals

Human Health Clinicians

TRAVEL MEDICINE

Travel medicine is a medical discipline that deals with prevention of infectious diseases during international travel as well as the personal safety of travelers and the avoidance of environmental risks during travel.3 Medical providers who care for human beings traveling to other countries need to be aware of the principles of travel medicine and be able to perform the functions of pretravel risk assessment and preventive counseling, vaccination, and posttravel evaluation of illness. A complete discussion of the many travel-related health risks is beyond the scope of this book. However, Table 10-1 shows the key elements of travel medicine practice.

Table 10-1 Elements of Travel Medicine Practice

Rights were not granted to include this table in electronic media. Please refer to the printed book.

From Hill DR, Ericsson CD, Pearson RD et al: The practice of travel medicine: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, Clin Infect Dis 43:1499, 2006.

PRETRAVEL RISK ASSESSMENT AND ANIMAL CONTACT COUNSELING

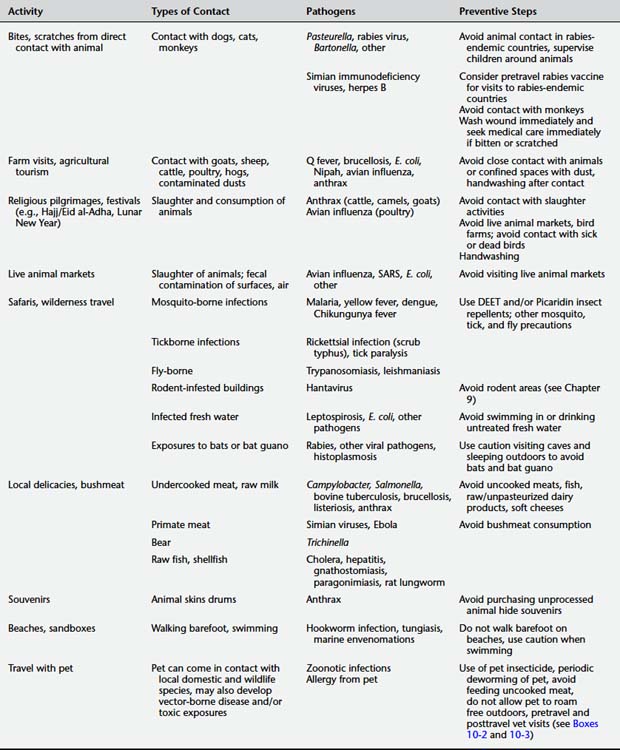

In a pretravel risk assessment, clinicians consider both the medical status of the traveler as well as the infectious and other environmental risks related to the countries they plan to visit and the activities they plan to undertake (see Table 10-1). Risks of travel-related animal contact may be overlooked during such visits. Table 10-2 summarizes these risks and provides the basics of counseling on risk reduction for particular animal contact situations.

HUMAN HEALTH RISKS OF ANIMAL CONTACT WHILE TRAVELING

Injuries From Animals

Animal bites and other animal-related injuries can be a significant hazard during travel (Color Plate 10-1). Although an attack from a wild animal, including snakes, crocodiles, large felids, and elephants, can cause dramatic injuries, falls from horseback or attacks by bulls or other large domestic animals can also maim and kill (Figures 10-1 and 10-2; Color Plates 10-2 and 10-3). A review of animal-associated injuries reported to the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network found that dog bites were the most common animal-associated injury to travelers, followed by bites from monkeys and cats. Three-quarters of the exposures occurred in countries where rabies is endemic, with the majority occurring in Asia. Fifty percent of bitten travelers had a travel duration of 1 month or less, and traveling for tourism was associated with an increased risk of an animal injury. Males were more likely to receive a dog bite, whereas monkey exposures were more common for females. Children were also at increased risk of exposure.4 Despite the risk of rabies from such exposures (fatal cases of human rabies have occurred in U.S. travelers from dog bites received during international travel5), a study of returning travelers with animal injuries found that most had not had pretravel rabies vaccine6 and two thirds of persons with injuries did not receive postexposure prophylaxis (which may not be routinely available in some countries). Rabies vaccine should be considered for all travel to rabies-endemic countries, especially for children, although a minimum travel duration of 6 weeks in an endemic area is recommended by some experts as an indication for vaccine. The strength of that recommendation should be influenced by the availability of medical care and rabies immunization products locally.

Figure 10-1 Wound from bison goring.

(From Auerbach PS: Wilderness medicine, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2007, Mosby Elsevier. Photo courtesy Karen Hansen.)

Figure 10-2 African elephant bluff-charges the photographer.

(From Auerbach PS: Wilderness medicine, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2007, Mosby Elsevier. Photo courtesy Cary Breidenthal.)

Exposure to nonhuman primates can occur during travel; monkey temples are a popular tourist site in Asia. Simian foamy virus infection has been reported in a visitor to a monkey temple.7 Bites from Old World monkeys also carry a risk of herpes B infection that can cause fatal disease in human beings (see Animal and Human Bites later in this chapter). Herpes B infections in human beings have been mostly observed in occupational settings (see Chapter 12), and to date no known cases have been reported in travelers.8

Travelers should never try to pet, handle, or feed unfamiliar animals, domestic or wild, particularly in areas of endemic rabies. Because children are at greatest risk of animal bites, including severe injuries, and may be less likely to report a bite incident,8 they need to be counseled to avoid petting or handling dogs, cats, or other animals and should be supervised around animals at all times. If an exposure occurs, clean the wound thoroughly and immediately seek medical care for possible rabies postexposure prophylaxis (see Chapter 9). Tetanus prophylaxis is also indicated if the traveler is not up to date with tetanus vaccination. In the case of an Old World monkey bite, medical care should be sought as soon as possible for prophylactic treatment against herpes B infection.

Envenomations from snakes, scorpions, and spiders represent another animal-associated injury risk to travelers; medical care should be sought immediately. The treatment of snakebites and other venomous animal bites usually depends on the species of animal responsible (see Chapter 8).

Farm Visits

Agricultural tourism is the experience of visiting a working farm or related operation for enjoyment and is a growing type of tourism both nationally and internationally (Figure 10-3).9 Specialized tour operators offer package tours to farms in a number of countries. During such visits tourists may come in contact with both farm animals and contaminated soils and dusts that may contain infectious pathogens. Q fever is considered to be underdiagnosed in travelers, who can acquire it by exposure to farm animals or contaminated aerosols.10 Travel to a farm in Guyana was associated with a cluster of human cases of Q fever, presumably from contact with a parturient goat and dog on a farm.11 If the farm contains poultry, risks include exposure to Chlamydophila, Campylobacter, Salmonella, and avian influenza virus. Brucellosis is another potential farm-related exposure, either through direct contact with animals or consumption of unpasteurized dairy products. Brucellosis has been termed a “travel-associated foodborne zoonosis” in Germany, where a recent rise in cases has been traced to consumption of unpasteurized cheese from brucellosis-endemic countries.12 In a series of brucellosis cases in San Diego, travel to Mexico was a risk factor for infection.13

Festivals Involving Animal Contact

An increasing amount of international travel is related to religious and cultural festivals. Each year several million Muslims participate in the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca. Although local agricultural authorities have taken steps to reduce animal contact risks to pilgrims,14 the end of the Hajj is marked by the festival of Eid al-Adha, which may involve increased exposure to animal slaughtering activities. For example, a suspected outbreak of anthrax was linked to slaughter and distribution of infected meat from a camel during the festival.15

Similarly, the Lunar New Year festivals in Asia often involve increased slaughtering and consumption of poultry, with an attendant increased risk of avian influenza. The CDC has issued travel advisories for U.S. travelers visiting Asia during the Lunar New Year festival. These recommendations include handwashing; avoidance of bird farms or live bird markets; not touching live or dead birds, including chickens, ducks, and wild birds, even if they do not seem sick; and not touching surfaces contaminated with bird feces, blood, or other body fluids.16

Live Animal Markets

At any time of year visits to live animal markets, present in many cities and villages in a large number of countries, carry a risk of infection with zoonotic agents. In such markets numerous species of wildlife and domestic animals may be housed in close proximity, creating an increased opportunity for disease transmission. Color Plate 10-4 shows a typical scene from a live animal market in Asia. Human infection with the H5N1 avian influenza virus has been linked to visits to live bird markets, even for individuals who denied direct contact with sick or healthy-appearing poultry.17 Avian influenza has been found on surfaces and dusts in such markets, and exposure may occur by touching contaminated surfaces as well as breathing contaminated dusts. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is another infection linked to live animal markets in Asia. Travelers wishing to reduce risk of zoonotic diseases while traveling should avoid visiting live animal markets, especially if a country is experiencing an outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza.18 A current list of countries is maintained at http://www.cdc.gov/flu/avian/outbreaks/current.htm.

Safaris and Wilderness Travel

Wilderness travel overseas increases the risk of exposure to a number of pathogens as well as injuries from snakes, crocodiles, and other wildlife. Visitors on safari to game parks in Africa have become infected with African tick fever and other rickettsial infections that may have a reservoir in the local wildlife populations.19 Although most forms of malaria, one of the most common causes of fever in returning travelers, are not zoonotic, certain monkey malaria species such as Plasmodium knowlesi have been described in human beings and may be underdiagnosed.20 Other zoonotic arthropod-borne infections such as trypanosomiasis, yellow fever, and Chikungunya fever have been reported in safari and wilderness travelers.21,22 Sleeping in huts and shelters that may also be home to local rodent populations can increase risk of infection with hantaviruses and various hemorrhagic fevers, including Lassa fever.23 Swimming in fresh water in areas frequented by wildlife has led to outbreaks of leptospirosis in adventure travelers.24 Wilderness travelers may be exposed to bats when visiting caves or sleeping outside in areas frequented by bats, where they could come in contact with bat droppings or sustain bat bites. In addition to rabies risk, bats are reservoirs for a wide range of other viral pathogens, including other lyssa viruses, Nipah virus, SARS-like coronavirus, and Marburg virus.25 Exposure to aerosolized bat guano has also been associated with the development of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis in travelers.26

Local Delicacies Involving Animal Products and Bushmeat Consumption

Many local delicacies that travelers encounter may involve animal products from domestic or wild animals. Meat and dairy products may be served raw or undercooked and may be a source for zoonotic infections such as brucellosis, trichinosis, and salmonellosis in returning travelers.27 Raw chicken sashimi from an island in Japan is known to be contaminated with Campylobacter. However, local residents do not appear to become ill, suggesting a role for acquired protective immunity that a traveler would presumably not enjoy.28 Travelers to Southeast Asia and Africa have become infected with parasites, including Paragonimus, trematodes Clonorchis sinensis or Haplorchis pumilio, and gnathostomes. Paragonimiasis is acquired by eating raw freshwater crabs or crayfish. Gnathostomiasis is a nematode infection acquired by ingestion of various intermediate hosts in addition to fish.29,30 Eating unwashed produce and undercooked foods such as mollusks in some countries poses risks of numerous infectious diseases, including viral hepatitis, bacterial enteritis, and eosinophilic meningitis from rat lungworm.31 There is increasing awareness of the infectious risks of improperly cooked poultry products. Such practices have been linked to cases of avian influenza.32 Bovine tuberculosis transmission to human beings can involve consumption of uncooked meat as well as raw milk (see Chapter 9).33

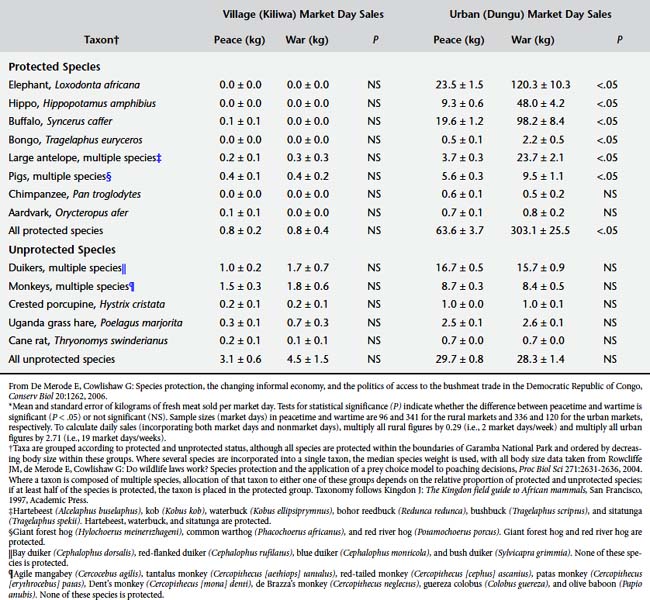

Bushmeat (wild game killed for food) is an important source of animal protein for communities in many parts of the world. It has been estimated that in Central Africa alone more than 1 billion kilograms of meat from wild animals are consumed each year (Figure 10-4).34Table 10-3 shows the diversity of species that may end up being sold for human consumption, especially during times of civil unrest.35 Emerging pathogens linked to bushmeat consumption include simian immunodeficiency viruses, anthrax, and hemorrhagic fever viruses.36 Although the risk of infection from bushmeat exposure may be greatest to persons who butcher carcasses, travelers to areas where bushmeat is an important part of local diets may be at risk if they consume improperly cooked bushmeat.

Figure 10-4 South African market with bushmeat for sale.

(From Fowler ME: Zoo and wild animal medicine: current therapy, ed 6, St Louis, 2008, Saunders Elsevier. Photo courtesy R. A. Cook.)

Beaches and Sandboxes

Travelers should avoid going barefoot on beaches frequented by animals. Many beaches that travelers visit during international vacations are frequented by dogs and cats. Walking barefoot on beaches contaminated with their feces is a risk factor for acquiring zoonotic hookworm infection (cutaneous larva migrans, also known as creeping eruption (see Chapter 9 and Color Plate 9-33).37 Another beach-related zoonosis is tungiasis, a skin infestation caused by the sand flea Tunga penetrans (jiggers). Walking barefoot on beaches also carries risks of stings from jellyfish and other marine organisms (see Chapter 8). Sandboxes and play areas are another source of contact for hookworms, roundworms (Toxocara), and Toxoplasma.

POSTTRAVEL ASSESSMENT

In the returning traveler with illness, a careful history of animal-related exposures should be obtained in addition to the standard questions (Box 10-1). If the response to any of these questions is affirmative, further evaluation is warranted.

TRAVELING WITH A PET AND OTHER ANIMAL TRAVEL MEDICINE ISSUES

Traveling with pets is becoming increasingly popular. There are a number of reasons why people travel with a pet. These include emotional, economic, gene transfer, and seeking specialized veterinary care.39 Emotional reasons include companionship, treating an animal as a member of the family, and reluctance to leave an animal behind. Economic factors can include the cost of arranging care for the animal while traveling. Gene transfer involves activities such as taking a pedigreed animal to another location to breed with another animal. Finally, owners may take an ill animal to another location for specialized veterinary care.39

Infectious Disease Risks and Pets That Travel

Particular zoonoses associated with dog travel include rabies, leishmaniasis, and roundworm infection.40–43 A case of a rabid puppy imported illegally from Morocco to France by a traveling couple resulted in the prophylactic treatment of 21 persons, the euthanasia of a contact animal, and legal action against the travelers.44 In 2007, a puppy rescued from an animal shelter in India by a veterinarian who brought the animal into the United States at 11 weeks of age was found to be positive for rabies by the Alaska Department of Health and Social Services.45 Such introduction of rabies from animal travel can involve foreign rabies virus variants. As a result, the CDC is considering strengthening federal regulations regarding the importation of companion animals.2

Other Risks Associated With Traveling Animals

Toxic risks to traveling animals include contaminated pet food,46 water, pesticides, and accidental ingestion of rodenticides (see Chapter 8).

Logistics

Travelers wishing to travel with pets will need to identify the logistic requirements for transporting and housing the animal during travel. Airlines may vary in their rules regarding whether an animal can be carried in a pet container that can be placed under a seat, or whether all animals need to be placed in cargo. There have been instances of companion animals dying from heat and cold stress and other trauma while being shipped in cargo, and owners should be aware of the risks to animals undergoing air travel.47 There may be restrictions on the number of animals allowed. Rental car companies, trains, buses, and hotels may also have restrictive policies about pets. These policies should be clarified in advance of travel.

Documentation and Regulation of Animal Travel and Importation

Animals that travel often need documentation of vaccination status, tick or other prophylactic treatments, and a statement from a veterinarian that they are free of communicable disease and able to travel safely. Such documentation may be necessary for the animal to enter another country. Owners should contact the embassies of countries they plan to visit to go through the required entry processes as well as determine the U.S. clearance processes upon return.48 Policies of some countries may require an animal to be quarantined or destroyed without proper documentation. Additional information is available at http://www.aphis.usda.gov/import_export/animals/animal_exports.shtml.

Many countries limit movement of dogs and other animals based on rabies status. Dogs and cats generally cannot pass from a rabies-endemic country to a rabies-free country without a process of quarantine and/or vaccination documentation. Table 10-4 lists countries reporting no indigenous rabies in 2005.

Table 10-4 Countries and Political Units Reporting No Indigenous Cases of Rabies During 2005*

| Region | Countries |

|---|---|

| Africa | Cape Verde, Libya, Mauritius, Réunion, São Tome and Principe, Seychelles |

| Americas | North: Bermuda, St. Pierre et Miquelon Caribbean: Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Bahamas, Barbados, Cayman Islands, Dominica, Guadeloupe, Jamaica, Martinique, Montserrat, Netherlands Antilles, Saint Kitts (Saint Christopher) and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Martin, Saint Vincent and Grenadines, Turks and Caicos, Virgin Islands (U.K. and U.S.) South: Uruguay |

| Asia | Hong Kong, Japan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Malaysia (Sabah), Qatar, Singapore, United Arab Emirates |

| Europe | Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Czech Republic†, Denmark†, Finland, France†, Gibraltar, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Isle of Man, Italy, Luxemburg, Netherlands†, Norway, Portugal, Spain† (except Ceuta/Melilla), Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom† |

| Oceania‡ | Australia†, Northern Mariana Islands, Cook Islands, Fiji, French Polynesia, Guam, Hawaii, Kiribati, Micronesia, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Vanuatu |

* Bat rabies may exist in some areas that are reportedly free of rabies in other animals.

† Bat lyssa viruses are known to exist in these areas that are reportedly free of rabies in other animals.

‡ Most of Pacific Oceania is reportedly rabies free.

From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: CDC health information for international travel 2008: prevention of specific infectious diseases: rabies.http://wwwn.cdc.gov/travel/yellowBookCh4-Rabies.aspx#653.

A number of federal agencies are involved with regulation of animals entering the United States. The CDC regulates the importation into the United States of dogs, cats, turtles, bats, monkeys, and other animals as well as animal products capable of causing human disease (see http://wwwn.cdc.gov/travel/yellowBookCh7-AnimalImport.aspx).48 Pets taken out of the United States are subject to the same regulations when returning to the country as are newly imported animals. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) regulates a number of species being imported based on their disease risk to plants and animals of agricultural concern.

No single agency regulates entry of dogs into the United States. Although the CDC does not require a general certificate of health for dogs, dogs with evidence of illness may not be allowed entry. Documentation of rabies vaccination at least 30 days before entry is required, although dogs younger than 3 months and dogs without proof of rabies vaccination may be allowed to enter if the owner completes a confinement agreement and certifies the animal will be vaccinated and kept confined at least 30 days after vaccination. Unvaccinated dogs from countries considered rabies free (see Table 10-4) may also be allowed entry.49 In addition to CDC regulations, the USDA regulates the importation of dogs potentially carrying diseases of agricultural importance, including screwworms or some Taenia species of tapeworm.2

For cats, a general certificate of health is not required to enter the United States, but some states and air carriers may require such documentation. Rabies vaccination is also not required, but some states may require proof of rabies vaccine documentation. All pet cats entering Hawaii and Guam are subject to local quarantine requirements.49

Importation of birds is regulated by the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service.50 The USDA currently restricts importation of pet birds from countries where highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 is present in poultry. To import a pet bird of non-U.S. origin, the importer or owner must obtain a USDA import permit,51 have a certificate of health from a veterinarian in the exporting country, and allow the bird to be quarantined for 30 days in a USDA animal import center at the owner’s expense. Pet birds arriving from Canada are not required to be quarantined.52 Entry into the United States of birds that are covered by endangered species conventions is regulated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Finally, importation of certain animals and animal products is regulated by other federal agencies such as the U.S. Customs Service.53

If animals are traveling, they should have a veterinary evaluation for pretravel risk assessment and administration of necessary vaccines and other preventive treatments. Box 10-2 outlines the elements of such a visit.

BOX 10-2 PRETRAVEL RISK ASSESSMENT CHECKLIST FOR PET

Health and Appropriateness of Animal

Evaluation of Illness in an Animal After Travel

Animals imported into the United States are required to be healthy. However, if illness develops, evaluation should involve the steps outlined in Box 10-3. If infectious conditions are identified, the possibility of zoonotic transmission to the animal’s owner should be considered, and there should be rapid communication to either a human health care provider, public health department, or both.

BOX 10-3 EVALUATION OF AN ILL PET AFTER TRAVEL

Further steps should be based on the results of this preliminary evaluation.

1. Office of Travel & Tourism Industries. U.S. citizen air traffic to overseas regions, Canada and Mexico, 2007. http://tinet.ita.doc.gov/view/m-2007-O-001/index.html. Accessed February 28, 2008

2. McQuiston J.H., Wilson T., Harris S., et al. Importation of dogs into the United States: risks from rabies and other zoonotic diseases. Zoonoses and Public Health. 2008;55(8–10):421-426.

3. Hill D.R., Ericsson C.D., Pearson R.D., et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America: The practice of travel medicine: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis.. 2006;43(12):1499-1539.

4. Gautret P., Schwartz E., Shaw M., et al. GeoSentinel Surveillance Network Animal-associated injuries and related diseases among returned travelers: a review of the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Vaccine. 2007;25(14):2656-2663.

5. Schmiedel S., Panning M., Lohse A., et al. Case report on fatal human rabies infection in Hamburg, Germany, March 2007. Euro Surveill. 2007;12(5):E070531.5.

6. Gautret P., Shaw M., Gazin P., et al. Rabies postexposure prophylaxis in returned injured travelers from France, Australia, and New Zealand: a retrospective study. Travel Med.. 2008;15(1):25-30.

7. Jones-Engel L., Engel G.A., Schillaci M.A., et al. Primate-to-human retroviral transmission in Asia. Emerg Infect Dis.. 2005;11(7):1028-1035.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC health information for international travel 2008: animal associated hazardshttp://wwwn.cdc.gov/travel/yellowBookCh6-Animal.aspx. Accessed October 16, 2008.

9. Lobo R, Small Farm Center, University of California-Davis. Helpful agricultural tourism (agritourism) definitionshttp://www.sfc.ucdavis.edu/agritourism/definition.html. Accessed May 29, 2008.

10. Terheggen U., Leggat P.A. Clinical manifestations of Q fever in adults and children. Travel Med Infect Dis.. 2007;5(3):159-164.

11. Baret M., Klement E., Dos Santos G., et al. Coxiella burnetii pneumopathy on return from French Guiana [in French]. Bulletin de la Societe de Pathologie Exotique. 2000;93(5):325-327,.

12. Dahouk S.A., Neubauer H., Hensel A., et al. Changing epidemiology of human brucellosis, Germany, 1962–2005. Emerg Infect Dis.. 2007;13(12):1895-1900.

13. Troy S.B., Rickman L.S., Davis C.E. Brucellosis in San Diego: epidemiology and species-related differences in acute clinical presentations. Medicine. 2005;84(3):174-187.

14. Ahmed Q.A., Arabi Y.M., Memish Z.A. Health risks at the Hajj. Lancet. 2006;367(9515):1008-1015.

15. International Society for Infectious Diseases: Dengue/DHF update 2008. http://promedmail.org.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In the news: keeping yourself safe from bird flu: an important message for people traveling to Asia to celebrate the Lunar New Year, 2008. http://wwwn.cdc.gov/travel/content AvianFluLunarNewYear08.aspx. Accessed February 28, 2008

17. Yu H., Feng Z., Zhang X., et al. Avian influenza H5N1 study group. Human influenza A (H5N1) cases, urban areas of People’s Republic of China, 2005–2006. Emerg Infect Dis.. 2007;13(7):1061-1064.

18. Hurtado T.R. Human influenza A (H5N1): a brief review and recommendations for travelers. Wilderness Environ Med.. 2006;17(4):276-281.

19. Buchau A.S., Wurthner J.U., Reifenberger J., et al. Fever, episcleritis, epistaxis, and rash after safari holiday in Swaziland. Arch. Dermatol.. 2006;142(10):1365-1366.

20. Ng O.T., Ooi E.E., Lee C.C., et al. Naturally acquired human Plasmodium knowlesi infection, Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis.. 2008;14(5):814-816.

21. Jelinek T., Bisoffi Z., Bonazzi L., et al. European Network on Imported Infectious Disease Surveillance. Cluster of African trypanosomiasis in travelers to Tanzanian national parks. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(6):634-635.

22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chikungunya fever diagnosed among international travelers—United States, 2005–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.. 2006;55(38):1040-1042.

23. Castillo C., Nicklas C., Mardones J., et al. Andes hantavirus as possible cause of disease in travellers to South America. Travel Med Infect Dis.. 2007;5(1):30-34.

24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of acute febrile illness among participants in EcoChallenge Sabah 2000-Malaysia, 2000. JAMA. 2000;284(13):1646.

25. Wong S., Lau S., Woo P., et al. Bats as a continuing source of emerging infections in humans. Rev Med Virol.. 2007;17(2):67-91.

26. de Vries P.J., Koolen M.G., Mulder M.M., et al. Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis from Ghana. Travel Med Infect Dis.. 2006;4(5):286-289.

27. Dore K., Buxton J., Henry B., et al. Multi-provincial Salmonella Typhimurium case-control study steering committee. Risk factors for Salmonella typhimurium DT104 and non-DT104 infection: a Canadian multi-provincial case-control study. Epidemiol Infect. 2004;132(3):485-493.

28. Moore J.E., Matsuda M. Consumption of raw chicken sashimi, Kyushu Island, Japan—risk of campylobacteriosis or not. Travel Med Infect Dis.. 2007;5(1):64-65.

29. Del Giudice P., Cua E., Le Fichoux Y., et al. Gnathostomiasis: an emerging parasitic disease [in French]? Ann Dermatol Venereol.. 2005;132(12 Pt 1):983-985.

30. Hale D.C., Blumberg L., Frean J. Case report: gnathostomiasis in two travelers to Zambia. Am J Trop Med Hyg.. 2003;68(6):707-709.

31. Weir E. Travel warning: eosinophilic meningitis caused by rat lungworm. CMAJ. 2002;166(9):1184.

32. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines and recommendations: interim guidance about avian influenza (H5N1) for U.S. citizens living abroadhttp://wwwn.cdc.gov/travel/contentAvianFluAmericans Abroad.aspx. Accessed February 28, 2008.

33. Etter E., Donado P., Jori F., et al. Risk analysis and bovine tuberculosis, a re-emerging zoonosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci.. 2006;1081:61-73.

34. Karesh W.B., Cook R.A. The human-animal link. Foreign Affairs. 2005;84:38-50.

35. De Merode E., Cowlishaw G. Species protection, the changing informal economy, and the politics of access to the bushmeat trade in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Conserv Biol.. 2006;20(4):1262-1271.

36. Wolfe N.D., Daszak P., Kilpatrick A.M., et al. Bushmeat hunting, deforestation, and prediction of zoonoses emergence. Emerg Infect Dis.. 2005;11(12):1822-1827.

37. van Nispen tot Pannerden C., van Gompel F., Rijnders BJ., et al. An itchy holiday. Neth J Med.. 2007;65(5):188-190.

38. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Anthrax Q&A: anthrax and animal hideshttp://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/anthrax/faq/pelt.asp. Accessed March 29, 2008.

39. Leggat PA., Speare R. Travel with pets. J Travel Med.. 2000;7:325-329.

40. Deplazes P., Staebler S., Gottstein B. Travel medicine of parasitic diseases in the dog [in German]. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd.. 2006;148(9):447-461.

41. Barr F., British Small Animal Veterinary Association Scientific Committee. Checklist of infections that may be imported into the UK by the travelling pet. J Small Anim Pract.. 2001;42(2):95-97.

42. Teske E., van Knapen F., Beijer EG., et al. Risk of infection with Leishmania spp. in the canine population in The Netherlands. Acta Vet Scand.. 2002;43(4):195-201.

43. Impact of pet travel on animal and public health. Vet Rec.. 2008;162(14):429-430.

44. Galperine T., Neau D., Moiton MP., et al. The risk of rabies in France and the illegal importation of animals from rabid endemic countries [in French]. Presse Med.. 2004;33(12 Pt 1):791-792.

45. Castrodale L., Walker V., Baldwin J., et al. Rabies in a puppy imported from India to the USA March 2007. Zoonoses and Public Health. 2008;55(8–10):427-430.

46. Brown CA., Jeong KS., Poppenga RH., et al. Outbreaks of renal failure associated with melamine and cyanuric acid in dogs and cats in 2004 and 2007. J Vet Diagn Invest.. 2007;19(5):525-531.

47. Humane Society of the United States. Tips for safe pet air travelhttp://www.hsus.org/pets/pet_care/caring_for_pets_when_you_travel/traveling_by_air_with_pets/. Accessed October 21, 2008.

48. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Importation of pets, other animals, and animal products into the United Stateshttp://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dq/animal/index.htm. Accessed February 28, 2008.

49. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Bringing an animal into the United Stateshttp://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dq/animal/dogs.htm. Accessed October 21, 2008.

50. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Pet travel: tips, facts, and scam information—for you and your pethttp://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_welfare/pet_travel/content/wp_c_pet_travel_tips.shtml. Accessed May 29, 2008.

51. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Animal health permitshttp://www.aphis.usda.gov/permits/index.shtml. Accessed October 15, 2008.

52. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Animal and animal product import: non-US origin pet birdshttp://www.aphis.usda.gov/import_export/animals/nonus_pet_bird.shtml. Accessed October 10, 2008.

53. U.S. Customs Service. Pets and wildlifehttp://www.cbp.gov/linkhandler/cgov/newsroom/publications/travel/pets_wild.ctt/pets.pdf. Accessed May 29, 2008.

EXOTIC AND WILDLIFE PETS

Animal and human health clinicians need to understand the scope of the exotic and wildlife pet trade, the related health risks, and ways to reduce such risks. Driven by popular demand, trade in live animals for pets has been increasing both in the United States and worldwide.1 More than 200 million animals, representing thousands of individual species, are estimated to be legally imported into the United States from more than 160 countries. The majority of these imports were for the pet and aquarium trade.2 The number of animals illegally imported each year is unknown but is also believed to be considerable.3 As a result, the United States is the world’s largest importer of live animals.2 At the same time, many potential pet owners are unaware of the health risks of such nontraditional pets.4

Key Points for Clinicians and Public Health Professionals

Public Health Professionals

Develop comprehensive federal regulations with enforcement that provide oversight to the private ownership of exotic and wild animals.

Develop comprehensive federal regulations with enforcement that provide oversight to the private ownership of exotic and wild animals. Improve regulation and inspection of exotic animal breeders, dealers, auctions, swap meets, Internet sales, pet outlets, and animal imports.

Improve regulation and inspection of exotic animal breeders, dealers, auctions, swap meets, Internet sales, pet outlets, and animal imports.Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree