∗ , Aubrey H. Fine † , Ann Berger ∗

∗National Institutes of Health

†California State Polytechnic University

16.1 Introduction

This chapter discusses how palliative care is being extended to relieve the disease symptoms, side effects, and associated burdens that can beset a patient at many points along the course of an illness. The addition of integrative modalities has been particularly helpful in enabling palliative care to be very successfully applied well beyond its historical roots in end-of-life care.

Part one (Extending palliative care through an integrative approach) presents a successful demonstration of how the principles and practices of integrative palliative care can outperform palliative care that lacks integrative modalities in terms of both the range of service provided and the degree of patient satisfaction. We present an example of how a growing number of pain and palliative care services are very successfully incorporating integrative care into their routine practice and delivering better service. This approach has not only given us more tools to perform our service, but has extended our practice far beyond its traditional boundary of end-of-life comfort (as illustrated in the account above) into comprehensive health care starting at the early stages of any serious illness and continuing on through the disease trajectory. The take-home message is that not only can an integrative approach to health care be welcomed and provide very substantial improvements of service within traditional medical settings, but an integrative approach can enable a health care consulting service to expand far beyond its original boundaries.

Part two (Meeting the challenges of research on healing in palliative care) addresses the special challenges facing medical researchers when designing experiments to understand subjective human responses to caring—either from animals, from other humans, or from one’s self. What provides the strongest evidence to document the outcomes of animal-assisted intervention (AAI) programs, or palliative care services, or any program aimed at improving people’s subjective experience of living? The caring stimulus, the variety of situational factors, and the subjective response are all complex, and the research strategy must be designed to capture complex data. We discuss why combined methodologies—both qualitative and quantitative—provide much stronger evidence from complex data than quantitative assessments alone. Two examples of highly successful research program strategies that made excellent use of both qualitative and quantitative methodologies are described, along with the application of combined methodologies in our current research on psycho-socio-spiritual healing.

Part three (The role of pet companions in supporting persons with chronic disease or terminal illness) discusses in theory and in practice how animal companions and animal-assisted therapy may be applied in palliative care. We describe research and integrative clinical programs that utilize or are relevant to animal companionship or animal-assisted intervention in palliative care. Based on these findings, we suggest ways in which animal companions and animal-assisted intervention may be incorporated into the practice of palliative care.

16.2 Extending palliative care through an integrative approach

Great strides have been made in the treatment of many diseases in recent decades to the extent that virtually half of persons who develop cancer can be cured. While the goal of medical practice is primarily battling the disease itself and the relief of symptoms is a secondary goal, the goal of palliative care is concerned with ameliorating symptoms, relieving suffering, and enhancing quality of life. Whether a disease can be cured—or whether one can hope only management of its progression or for limited remission—the patient most acutely feels the physical, psychosocial, and spiritual symptoms associated with the disease and its treatment. Do we think that the goals of fighting disease and palliative care are disparate? Absolutely not! Supportive or palliative, yes, but of lesser importance? Not to the patient who feels a great burden from a serious illness!

As has always been the case, the patient with chronic or life-threatening disease is often acutely aware of those symptoms that are under the rubric of supportive/palliative care. All too frequently physical symptoms are experienced such as fatigue and anemia, pain, nausea, constipation, oral mucositis, anxiety and depression. Patients experience not only physical symptoms, but also significant psycho-socio-spiritual issues that can weigh heavily on a patient and influence their health. For example, even if a fortunate patient is not currently suffering from symptoms listed above, they may actively fear them. Their fear can exacerbate undesirable symptoms, complicate treatment, and have a detrimental effect on the quality of life of both the patient and the patient’s family.

There are many promising new disease treatments—Alzheimer’s, cardiovascular, cancer, HIV, to name a few—both in development and on the horizon. No matter what these new treatments will offer in terms of curing the illness or prolonging life, many are likely to retain their reputations as devastating diseases, not only for the affected patients but for their families, the community, and health care providers. One always hopes to cure a patient, but even with cure, one hopes for the patient to be healed in the process—to enjoy a more meaningful quality of life. And certainly when a person cannot be cured, one can still die healed—having a sense of wholeness as a person. As health care professionals we often feel a clear responsibility to ensure that the patient with a chronic or life-threatening illness has a chance of being both cured and healed! We may not always be able to add days to lives, but we can add life to days.

16.2.1 Healing versus curing—an unnecessary either/or dilemma

Those patients who come to … medical experts for the most advanced treatment of their disease have a right to expect far more than mere technological efforts. There is no inconsistency between the ability to achieve great diagnostic and therapeutic victories and the ability to provide comfort when those victories are beyond reach.

(Dan) Frimmer’s favorite saying in the last months of his life was, “You can’t die cured, but you can die healed.” What did he mean? Explained his rabbi, Arnold Gluck: “Healing is about a sense of wholeness as a person, and that wholeness includes understanding our mortality, our place in the world…”

Living in a harmonious and supportive environment is desirable in any part of the lifespan, including the end of life. Palliative care is characterized as care that helps people live fully until they die (see Table 16.1). The World Health Organization (WHO, 2010) defines palliative care as “An approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual.” According to the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (2010), palliative care extends the principles of hospice care so that a broader population of people can receive beneficial care earlier in their disease process prior to the last six months of life when hospice typically begins. In addition to enhancing the quality of life, applying palliative care early in the course of illness in conjunction with other therapies may also positively influence the trajectory of the patient’s illness.

Table 16.1 Goals of palliative care

|

(WHO, 2005)

Since the introduction of end-of-life hospice/palliative care in the USA, its delivery to patients (and their families) has typically been subject to the bureaucratic restrictions of Medicare reimbursement regulations and life expectancy projections. The choice of medical services is often seen in “either/or” terms: “either” aggressive treatment (often fragmented) attempting to cure, “or” integrative interdisciplinary comfort care only after all curative efforts have failed.

Why not deliver both attempts (to cure and to comfort) at the same time? Both research and clinical literature report high patient and caregiver satisfaction with the interdisciplinary, integrative approach—not only in end-of-life care but in symptom management at all phases of health care. However, in most settings there are restrictions on the delivery of health care services that result in reimbursement for the interdisciplinary, integrative approach not being allowed until curative efforts have stopped. Statistics reveal that this situation has significantly impacted willingness to utilize this scope of service, since it imposes on patients an “either/or” financial decision that often compromises their need to obtain comfort and retain hope for a possibly prolonged prognosis or even a cure.

All health care providers have the ethical responsibility to “first do no harm.” This includes alleviating the burden of the patient’s dilemma—having to choose between aggressive treatment or comfort care. Supporting a patient’s need for hope, their need for healing, their need for a sense of wholeness—these are so vital to a humane practice of medicine. Humanism in health care can be initiated by incorporating the proven principles learned by clinical experience in palliative care (a very successful model of integrative care) into mainstream general practice and across all specialty settings. Valuing the comfort and healing of a patient should not wait until the end of life. It should be implemented from the onset of a chronic disease diagnosis, fitting in quite naturally with the management of chronic pain. It should be continued throughout every day that the patient lives with the illness—just as aggressively as the efforts made to cure the patient.

Patients require both “high tech” and “high touch” care throughout their disease trajectory and sometimes beyond. The integrative, multidimensional, interdisciplinary approaches used in palliative care (or, more broadly, supportive care) can meet the patient’s clinical, scientific, and functional needs with compassion. By utilizing the principles of palliative care, including the back-to-basics of “bedside care” approach to treating individuals with chronic pain, a patient with pain may or may not be cured yet he/she can have the resources that fully support his/her healing.

16.2.2 What should be regarded and treated as chronic pain?

Pain is a huge quality of life issue. Its prevalence and inadequate control is well documented in patients with cancer pain as well as in patients with chronic pain not related to cancer. There are many consequences of pain: depression, decreased socialization, increased agitation, impaired mobility, slowed rehabilitation, malnutrition, sleep disturbances, more visits to the doctor and hospital, and others.

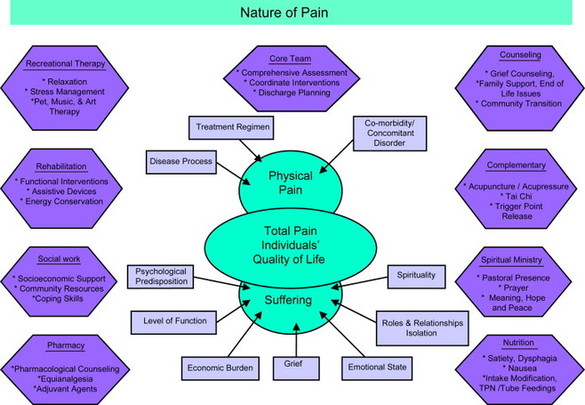

Pain is a mental experience that can have a wide range of significance within a patient’s medical condition. The total pain experienced by a patient is made up of more than just physical pain (see Figure 16.1). Total pain can involve a physical component as well as a suffering component. Suffering includes psychological and coping factors, social support, loss issues, fear of death, financial concerns, and spiritual concerns (such as the understanding and meaning of this difficult part of a patient’s life). Understandably, most patients with chronic pain have both physical pain and suffering.

Figure 16.1 Total pain experienced by a patient

Optimally, a team of care providers should be involved as needed to help relieve suffering. Most notably the team should include doctors and nurses who are familiar with pharmacological approaches to pain relief as well as those who work with non-pharmacologic approaches to relieving pain, such as social workers, pet therapists, spiritual care counselors, recreation therapists, art therapists, body work therapists (e.g. massage and Reiki therapists), music therapists, and volunteers (including family and friends). To treat total pain, pharmacologic and/or invasive approaches are needed to relieve physical symptoms and non-pharmacologic approaches are needed to relieve suffering.

Following the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for pain relief significantly reduces the severity of pain but it is clear that the published guidelines are not being followed. Many scientific research studies have made it clear that our society needs to make major changes in the way we recognize and treat different forms of pain. Recently, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) has required that all hospitals and nursing homes assess pain as a fifth vital sign, on par with blood pressure or pulse. The inability to relieve pain, even when we have the tools to do so, suggests that professional and patient education has been inadequate.

16.2.3 A provocative care structure that works

Care more particularly about the patient than for the special features of the disease.

(Sir William Osler) (Madison, 1997)

People who are dealing with any chronic illness, including chronic pain, experience various degrees of suffering. The way people deal with their suffering is mostly influenced by their own inner resources: their personality, coping styles, cultural background, and their personal meaning of life (Frankl, 1984). While pain has been described in the literature for centuries, it has been one of medicine’s greatest mysteries. It still remains a challenge for health care professionals to provide the best of care for the patient and his/her family. To treat suffering, we try to nudge the patient’s inner resources—much more through personal caring than through the impersonal procedures of illness treatment—to take them in the direction of healing. Whether it is through the patient’s own pets or through animal-assisted intervention (AAI), appropriate animals can strongly convey the caring that is so fundamental to opening the patient’s inner avenues of healing.

Several approaches are necessary to treat patients with chronic pain and alleviate suffering. First and foremost, we as health care providers need to recognize that we need to drop the barriers of our respective roles in order to communicate effectively with our patients on the human level of both caring and suffering. We need to understand that we are not all that different from our patients and that we, too, can have chronic pain and can understand their suffering. Of course, those barriers are often much less of an issue with pets. Second, we need to enter the patient and family system, comfortably, so that suffering can be understood and taken in the right context. Third, it is essential to validate the various feelings and emotions experienced by the patients as well as their family members as normal when facing a challenging situation such as chronic pain. Pets and animals can often bring out feelings in a patient, and thus make it easier for human care givers to validate and reinforce those positive feelings.

Palliative care and supportive care should involve the collaborative efforts of an interdisciplinary team. This team must include the patient with a chronic or life-threatening illness, his or her family, caregivers, as well as the group of involved health care providers. “Out of the box” creativity can be used as a provocative and wonderfully constructive structure within an integrative, palliative care model of relieving chronic pain. Recent advances in complementary, behavioral and pharmacologic therapies call for a renaissance in pain and palliative care medicine. The integrative, palliative care model is a holistic view with the patient and family always in the forefront. As an example, serving “high tea” (typifying tea for royalty) creates a comfortable milieu for the patient to shift away from suffering and share a happier, more desirable moment with family, friends and health caregivers. This offers a setting to converse, verbalize wishes and concerns or reminisce. Always remembering flexibility and hospitality for patients, families and other health care providers will help to break down sterile barriers and lighten the intensity level. We use team theme days such as “sun-fun,” “mardi gras,” signature hats and boas as a diversion patients welcome from white coat attire. Spontaneous celebrations of life such as setting the TV channel to a game played by an inpatient’s favorite football team, or sending an outpatient to a performance by his/her favorite musician, have reminded patients that their life is more than suffering.

16.3 Meeting the challenges of research on healing in palliative care

16.3.1 The need for strengthening evidence in psychosocial research

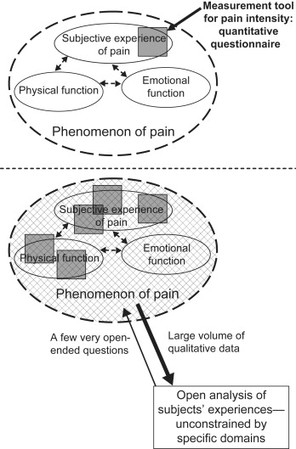

Behavioral research increasingly involves assessment of phenomena that are influenced by multiple dimensions: psychological, social, spiritual, and physical. A good example is the measurement of pain. The consensus among members of the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) is that six core domains should be considered in chronic pain clinical trials (Turk et al., 2003): (1) pain, (2) physical functioning, (3) emotional functioning, (4) participant ratings of improvement and satisfaction with treatment, (5) symptoms and adverse events, and (6) participant disposition. The large oval in the upper part of Figure 16.2 represents the set of all features of the target phenomenon (e.g. pain), the smaller internal ovals represent features within the phenomenon (e.g. subjective experience of pain, physical functioning, emotional functioning).

Figure 16.2 Core dimensions in chronic pain

Quantitative assessments enable the use of scales for precise comparisons. However, phenomena, features, structures, ranges and interactions are fundamentally identified and described in terms of qualities or properties. Therefore qualitative description is the core of any theory of a psycho-socio-spiritual phenomenon. The remainder of this section on meeting the challenge of research on healing in palliative care is concerned with some specifics of why and how to strengthen empirical evidence by combining qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

Quantitative assessment questionnaires (instruments or tools) and the items within them are typically associated with specific constructs. The ability to discriminate construct from non-construct (discriminant validity) gives the instrument specificity and meaning. However, this generally means that an existing, well-validated tool does not completely cover the phenomenon of interest. The challenge is apparent in Figure 16.2 (upper part): a typical quantitative tool can provide substantial strength of evidence for a feature (e.g. pain intensity) within its focus (e.g. the subjective experience of pain) but much of the target phenomenon of pain can be omitted. Depending on the nature of the pain (sharp and localized vs. non-specific; unvarying vs. widely varying), the nature of the patient’s illness (acute vs. chronic or even life-long), and on the relationship between physical pain and physical activity and emotional experiences, some patients have difficulty assigning a single position on a scale or a single number to their pain intensity. The problem of incomplete coverage is compounded because even the best of quantitative pain intensity measures is silent about what pain features and descriptors it has not captured, and no degree of statistical control in a quantitative study design will avoid silent omissions.

A study using a multi-assessment approach is designed to have greater strength of evidence than a study using a single tool, all other factors being equal (see lower part of Figure 16.2). However, there is still the problem that even the best group of standard, validated quantitative measures will be silent about any omitted features and interactions (e.g. pain intensity and emotional function). If the target phenomenon has any insufficiently explored or unique features (often the very thing that makes the phenomenon of interest to the researcher), the assessment obtained by the multi-assessment approach is not sure to uncover them.

16.3.2 Including open examination of a target phenomenon

An open examination of all discernible features of a phenomenon can substantially help identify any insufficiently explored or unanticipated features. Open examination aims to capture the entire range of first-hand experience that can be reported by the research subjects. This generally adds to the strength of any study, from a small isolated study to a large research program.

Not surprisingly, open examination is likely to involve a distinctly different methodology than that used for hypothesis testing. Qualitative methods are particularly appropriate when the research focus is on ensuring that we know the process of a phenomenon and not on a measurement of the outcome (Smith, 1996). In reflecting on her very substantial experience with performing well-recognized quantitative and qualitative studies, Beck (1997) comments, “…their vision of their research program should not be blinded by their lack of expertise in particular research methods…the investigator may need to cross over from inductive to deductive methods or vice versa at certain points in the research trajectory.” As a brief introduction to the tools of qualitative research, Beck describes six of the most common qualitative research designs and includes some examples from her own research to illustrate them (Beck, 2009).

The schematic diagram in the lower part of Figure 16.2 illustrates the complementary roles of these two sets of tools. The solid black rectangles represent well-validated quantitative assessment tools. The span of the target phenomenon’s feature set can be more fully covered by qualitative open examination (cross-hatched area). One of the great advantages of open qualitative data (e.g. narrative data) is that the researcher is not required to have prior knowledge or understanding of the features of the phenomena that may be evidenced in the narrative data. It is the complementary situation to quantitative assessment, for which the responses must always be predetermined through expert understanding. Inclusion of qualitative data in a study as a major component alongside quantitative data and analysis can also provide well-grounded corroborating evidence. This is represented by the areas in Figure 16.2 where quantitative (solid black rectangles) and qualitative analyses (cross-hatched entire domain of pain) overlap with each other. Some key features of combined research programs are summarized in Table 16.2.

Table 16.2 Strengthening evidence by combined studies

| Quantitative only | Combined: Quantitative + Qualitative |

| Multiple quantitative assessment instruments | Overlap of qualitative data with quantitative data adds corroboration obtained by independent methodology |

| Silent omission of features not targeted by multiple assessment tools | Open examination can capture features for which there is no measurement tool (e.g. phenomenological study) |

| Partial capture of model dynamics in uncontrolled settings | Open examination can capture dynamics for which there is no measurement tool (e.g. grounded theory study) |

| Uncontrolled settings contribute to limitations of study | Additional empirical data provide more information and may reduce limitations of study |

16.3.3 Comparing basic features of qualitative and quantitative research

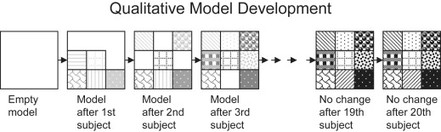

Combined research programs not only gather both quantitative and qualitative data, they also perform both quantitative and qualitative analyses. An understanding of their differences in analyses helps the research team gain the full advantages of both. The primary objective may be to achieve a comprehensive phenomenological model that is empirically grounded (generated only from the interview data itself), that is complete (contains all aspects of the phenomenon), that is self-consistent (all the parts fit together), and that forms a well-delineated construct (minimal ambiguity about where the construct of interest is bounded with respect to other constructs). Categorization of qualitative data is a systematic discovery process that is somewhat analogous to putting together a complete picture (the desired model) from jigsaw puzzle pieces (coded data) coming from several puzzle boxes (different constructs in the subject’s experience: healing, coping, etc.). As pieces are individually fitted together, objects in the picture (categories) start to become recognizable (left side of Figure 16.3). These recognizable objects in the picture (categories) can then speed up assembly. Some of the pieces are duplicates, and they are kept as reinforcements. Other pieces may belong to another picture. Their inconsistencies with respect to the picture need to be recognized, and they need to be saved in the appropriate box (not discarded) rather than trying to force those pieces into the picture (ignoring inconsistencies, or mixing constructs). As the puzzle is assembled, one constantly checks for missing pieces (gaps in the model)—the picture is not complete until there are no holes or irregular edges. In the end, it is much more the recognizable objects (categories) than the shape of the individual pieces (coded data) that make the picture (the model).

Figure 16.3 Qualitative model development

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree