Chapter 147 Heart Failure in Dogs

Heart failure (HF) is a state wherein the cardiac output is inadequate to meet the perfusion needs of the metabolizing tissues and exercise capacity is limited. The causes of HF in dogs are diverse, but there are stereotypical cardiovascular and systemic responses to impaired cardiac function, regardless of cause. This chapter provides a brief overview of HF; considers the causes and diagnoses of HF in dogs; and reviews treatment plans for management of the cardiac failure patient. The clinical pharmacology and pathophysiologic rationale for drugs used in treatment of HF are detailed in Chapter 146. Management of HF in cats is discussed in the chapter “Cardiomyopathy” (Chapter 150).

Overview

Heart failure is a not a specific disease but a pathophysiologic disorder. Some of the key abnormalities of this condition are summarized below, and the pathophysiologic rationale for using particular cardiovascular drugs is summarized in Chapter 146. The reader is directed to other textbooks for a detailed review of pathophysiology of HF.

Etiology

Classification

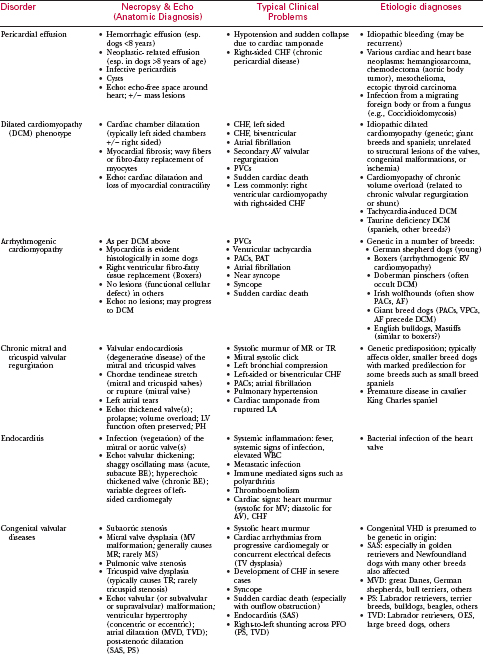

Table 147-1 OVERVIEW OF MORPHOLOGIC/ANATOMIC DIAGNOSES

Developmental disorder or malformation

Vascular change: congestion, edema, hemorrhage, thrombosis, infarction

Apoptosis (programmed cell death)

Disruptive defects such as trauma

Table 147-2 OVERVIEW OF ETIOLOGIC DIAGNOSES

D = developmental disorders; degenerative lesions

A = anomalies, autonomic dysfunction, anemia

N = neoplasia or nutritional disorder

I = infectious, inflammatory, ischemic, immune, iatrogenic and idiopathic diseases

Causes

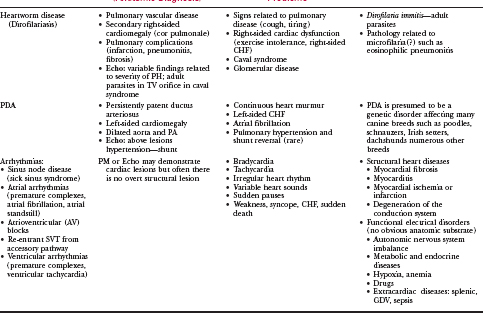

The most important causes of canine heart disease involve a limited number of acquired disorders and a handful of important congenital heart defects. These conditions, as well as usual diagnostic findings, are summarized in Table 147-4 and in other chapters across this section. The most important acquired cardiac disorders responsible for HF in dogs are:

The most important of the canine congenital heart defects include the following:

DIAGNOSIS

History and Clinical Signs

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree