Chapter 18 Hazards Associated with the Use of Herbal and Other Natural Products

Broadly defined, herbs are plants used for medicinal purposes or for their olfactory or flavoring properties. Herbs are also defined as dietary supplements by the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994, along with vitamins, minerals, and amino acids. There is increasing interest in the use of herbs and other “natural” products by both veterinarians and animal owners to treat medical problems (herbal medicine). The reasons underlying the increased use of herbal and other “alternative” medical modalities in human health have been investigated extensively and are multifactorial.1–3 Social, economic, and philosophical reasons often underlie the decision by an individual to turn to alternative modalities, such as herbal medicine. Unfortunately, similar investigations into the motivation of pet owners to employ such modalities for the treatment of their pets have not been conducted. However, it is likely that the same motivations apply.

Herbal medicine and conventional pharmacology differ in three fundamental ways.4 First, herbalists use unpurified plant extracts containing several different constituents in the belief that the various constituents work synergistically (the effect of the whole herb is greater than the summed effects of its individual components). In addition, herbalists believe that toxicity is reduced when the whole herb is used instead of its purified active constituents; this is termed “buffering.” Secondly, several herbs are often used together. The theories of synergism and buffering are believed to be applicable when herb combinations are employed. In conventional medicine, polypharmacy is generally not considered to be desirable because of increased risks of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) or interactions. Lastly, herbalists and many other alternative medical practitioners approach patients in a more “holistic” way than do many conventional medical practitioners who tend to focus more narrowly on the disease and exclude consideration of the patient as an individual.

REGULATIONS

In 1994 Congress passed the DSHEA, which limits government oversight of products categorized as dietary supplements. Dietary supplements include minerals, vitamins, amino acids, herbs and any product sold as a “dietary supplement” before October 15, 1994. Thus the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has little statutory authority to regulate such materials. As a result, herbal products can be marketed without prior testing for safety and efficacy, and they can be manufactured without regard to quality control. Thus a problem with some herbal or natural products is variation in concentrations of active ingredients. This can alter their expected efficacy or their potential for intoxication. In contrast proof of safety and efficacy are required by the FDA before marketing pre-scription and over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, and their manufacture is regulated to ensure a consistent product. The DSHEA allows dietary supplements to carry a statement on their labels that “describes the role of a nutrient or dietary ingredient intended to affect the structure or function” of the body. However, such products cannot contain drug claims, which are intended to “diagnose, mitigate, treat, cure, or prevent a specific disease or class of disease.” Thus an example of an acceptable claim on the label of an herbal product would be that the product “supports the immune system.” In contrast the claim that the product “supports the body’s ability to resist infection” is unacceptable. Currently, there is controversy between the FDA and the dietary supplement industry regarding the definition of “disease.”

ACTIVE HERBAL CONSTITUENTS

There are five broad classes of active chemical constituents in plants: volatile oils, resins, alkaloids, glycosides, and fixed oils.5 Volatile oils are odorous plant ingredients. Examples of plants that contain volatile oils include catnip, garlic, and citrus. Ingestion or dermal exposure to volatile oils can result in intoxication. Resins are complex chemical mixtures that can be strong gastrointestinal irritants. Alkaloids are a heterogeneous group of alkaline, organic, and nitrogenous compounds. Often these compounds are the most pharmacologically active plant constituents. Glycosides are sugar esters containing a sugar (glycol) and a nonsugar (aglycon). Glycosides are not typically toxic. However, hydrolysis of the glycosides after ingestion can release toxic aglycones. Fixed oils are esters of long chain fatty acids and alcohols. Herbs containing fixed oils are often used as emollients, demulcents, and bases for other agents; in general these are the least toxic of the plant constituents.

Many of these plant-derived chemicals are biologically active and, if exposure is of sufficient magnitude, potentially toxic. There are numerous case reports in the medical literature documenting serious and potentially life-threatening adverse effects following human and animal exposure to herbal preparations. It is worth noting that in several instances the incidence of animal intoxication from an herb, herbal preparation, or dietary supplement seems to parallel its popularity.6,7 However, it is important to point out that considered as a whole, the use of herbal products does not appear to be associated with a higher incidence of serious adverse effects than from ingestion of conventional prescription or OTC pharmaceuticals. Serious ADRs to conventional pharmaceuticals in hospitalized patients have been estimated to be approximately 6.7%.8 An approximately equal incidence of hospital admissions caused by ADRs has been reported.9 A recent study estimated that approximately 25% of all herbal remedy- and dietary supplement-related calls to a regional human poison control center could be classified as ADRs.10 The most common ADRs were associated with zinc (38.2%), echinacea (7.7%), chromium picolinate (6.4%), and witch hazel (6.0%). Only 3 out of 233 ADRs were considered to be serious enough to warrant hospitalization. It is likely that ADRs are underreported for both conventional drugs and herbal remedies. Unfortunately, there is almost no information regarding the overall incidence of ADRs to conventional drugs or herbal remedies in veterinary medicine.

There are various ways in which poisoning of an animal might occur. Use of a remedy that contains a known toxin is one possibility. For example, chronic use of an herbal remedy containing hepatotoxic pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs) may result in liver failure. Pennyroyal oil containing the putative hepatotoxin, pulegone, was responsible for the death of a dog after it was applied dermally to control fleas.11 Alternatively, administration of a misidentified plant may result in poisoning. Contamination of commercially prepared herbal remedies with toxic plants has been documented in the medical literature.12,13 Seeds of poison hemlock (Conium maculatum) have been found in anise seed. Recently, plantain sold as a dietary supplement was found to contain cardiac glycosides from Digitalis spp. Just as with traditional prescription medications, pet intoxication following accidental ingestion of an improperly stored remedy may occur. This is particularly true with dogs because of their indiscriminant eating habits. The author was involved in a case in which a miniature poodle ingested several tablets of its owner’s medication containing rauwolfia alkaloids and developed clinical signs within 2 hours of ingestion. Reserpine was detected in the medication and the urine of the dog.

Some herbal remedies, particularly Chinese patent medicines, may contain inorganic contaminants—such as arsenic, lead, or mercury—or intentionally added pharmaceuticals, such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatories, corticosteroids, caffeine, or sedatives.14 Commonly found natural toxins in Chinese patent medicines include borneol, aconite, toad secretions (Bufo spp., Ch’an Su), mylabris, scorpion, borax, acorus, and strychnine (Strychnos nux-vomica).14

Because herbal preparations contain numerous biologically active compounds, the potential exists for adverse drug interactions when they are used in conjunction with conventional pharmaceuticals. In addition, many naturally occurring chemicals found in herbal remedies cause induction of one or more liver cytochrome P450 metabolizing enzymes. For example, eucalyptus oil induces liver enzyme activity.15 This can result in altered metabolism of other drugs or chemicals resulting in either enhanced or diminished drug efficacy or toxicity. Coexisting liver or renal disease can alter the metabolism and elimination of herbal constituents, thus predisposing to adverse reactions. Apparent idiosyncratic reactions to herbal remedies have been documented in people. Such reactions might be due to individual differences in drug metabolizing capacity.16,17

According to annual surveys of herbs sold in the United States, the most commonly used herbs include coneflower (Echinacea spp.), garlic (Allium sativa), ginseng (Panax spp.), gingko (Ginkgo biloba), St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum), saw palmetto (Serenoa repens), goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis), aloe (Aloe spp.), astragalus (Astragalus spp.), cayenne (Capsicum spp.), bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus), and cat’s claw (Uncaria tomentosa). Presumably, these herbs would be those to which pets are most likely to be exposed. According to the recently published Botanic Safety Handbook, coneflower, saw palmetto, aloe (gel used internally), astragalus and cayenne (used internally) should be considered safe when used appropriately. Garlic, ginseng, gingko, St. John’s wort, goldenseal, aloe (gel used externally, dried juice used externally), and cayenne (used externally) have some restrictions for use.18 For example, in humans garlic should not be used by nursing mothers, and cayenne should not be applied to injured skin or near eyes. Both gingko and St. John’s wort are contraindicated in individuals taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors because of potential herb-drug interactions. There is insufficient data available for bilberry and cat’s claw to make a determination regarding their safety. Of interest is a recent study listing the most common herb-related calls to a regional human poison control center.19 The most frequent calls, in descending order of frequency, involved St. John’s wort, ma huang, echinacea, guarana, ginkgo, ginseng, valerian, tea tree oil, goldenseal, arnica, yohimbe, and kava kava. Not all of the calls could be categorized as ADRs.

SUMMARIES OF THE SAFETY OF COMMON HERBS

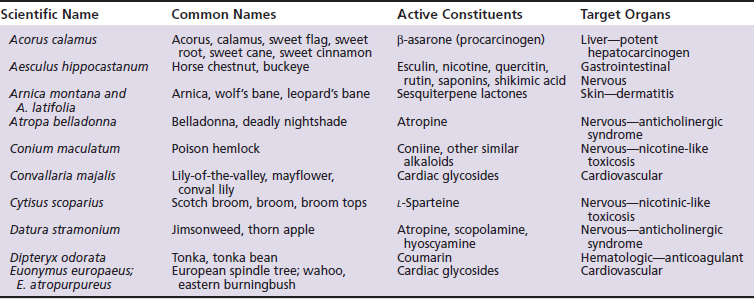

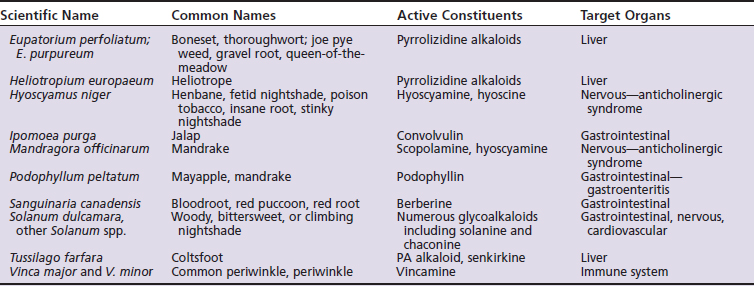

Not all of the following herbs, essential oils, and dietary supplements are used in herbal medicine because of well-recognized risks of intoxication. However, they are included in the following discussion precisely because of their inherent toxicity. Unless otherwise specified, the following information is taken from three primary sources: The Botanic Safety Handbook, The Complete German Commission E Monographs: Therapeutic Guide to Herbal Medicines, and The Review of Natural Products.18,20,21 Other herbs of toxicological concern are listed in Table 18-1.

5-Hydroxytryptophan

5-HTP, also known as Griffonia seed extract, is a popular dietary supplement that is available OTC for a variety of conditions including depression, chronic headaches, obesity, and insomnia in humans. A retrospective study by the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals-Animal Poison Control Center (ASPCA-APCC) reported 21 cases of accidental ingestion of products containing 5-HTP by dogs between 1989 and 1999.7 Clinical signs of intoxication developed in 19 of the 21 dogs and consisted primarily of seizures, depression, tremors, hyperesthesia, ataxia, and hyperthermia. Vomiting and diarrhea were also frequently reported. The pharmacological and toxicological action of 5-HTP is believed to be due to increased concentrations of serotonin in the central nervous system (CNS).22 The estimated minimum toxic oral dose from the APCC study was 23.6 mg/kg, and the minimum lethal oral dose was estimated to be 128 mg/kg. Three of the 19 symptomatic dogs died, and 16 of 17 dogs receiving symptomatic and supportive care recovered.

Absinthe (wormwood)

The name wormwood is derived from the ancient use of the plant (Artemesia absinthium) and its extracts as an intestinal anthelmintic. Wormwood was the main ingredient in absinthe, a largely banned, toxic liqueur whose chronic consumption was associated with absinthism. Absinthism was characterized by mental enfeeblement, hallucinations, psychosis, delirium, vertigo, trembling of the limbs, digestive disorders, thirst, paralysis, and death. α- and β-Thujone are the toxins found in wormwood. In rats, IV injection of thujone at 40 mg/kg and 120 mg/kg induces convulsions and death, respectively. According to the German Commission E, indications for the use of wormwood include loss of appetite, dyspepsia, and biliary dyskinesia. Thujone-free plant extract is used as a flavoring agent in alcoholic beverages, such as vermouth. The FDA classifies the plant as an unsafe herb. The American Herbal Products Association (AHPA) indicates that the herb should not be used during pregnancy or lactation or for long-term use.

Aconite

Traditionally, aconite (Aconitum spp.) root was used for topical analgesia, neuralgia, asthma, and heart disease. It contains several cardioactive alkaloids including aconitine, aconine, picraconitine, and napelline. These act on the heart by increasing sodium flux through sodium channels. Acute toxicosis can be induced following the ingestion of 5 mL of aconite tincture, 2 mg of pure aconitine or ∼1 g of the plant. Clinical signs include burning sensation of the lips, tongue, and throat, and gastrointestinal upset characterized by salivation, nausea, and emesis. Cardiac arrhythmias with unusual electrical characteristics have been observed following intoxication. Death can occur from minutes to days following ingestion. Although little used in the United States, it continues to be used in traditional medicine in Asia and Europe. The most common herb-related adverse reaction in China involves aconite root.14 The AHPA suggests that the herb be taken only under the advice of an expert qualified in its appropriate use.

Aristolochia

Traditionally the plant (Aristolochia spp.) has been used as an antiinflammatory agent and for the treatment of snakebites. More recently, it was found to be a contaminant of a weight loss preparation.13 The active ingredient in aristolochia is aristolochic acid, which is carcinogenic, mutagenic, and nephrotoxic. The rodent intravenous (IV) LD50 is 38 to 203 mg/kg. In rats doses as low as 5 mg/kg for 3 weeks have been associated with various neoplasias. This herb is not recommended for use.

Digitalis

Digitalis spp. contain several cardiac glycosides including digitoxin, gitoxin, and lanatosides that inhibit sodium-potassium adenosinetriphosphatase (ATPase) activity. All parts of the plant are toxic. Toxic doses of fresh leaves are reported to be ∼6 to 7 oz for a cow, ∼4 to 5 oz for a horse and less than 1 oz for a pig. Sucking on the flowers or ingesting seeds and leaves of the plant have intoxicated children. Ornamental varieties of digitalis contain notably lower concentrations of the glycosides. Clinical signs of intoxication include gastrointestinal upset, dizziness, weakness, muscle tremors, miosis, and potentially fatal cardiac arrhythmias. Digitalis glycosides have a relatively long half-life and may accumulate, leading to intoxication. Poisoning by digitalis is one of the few plant intoxications for which there is a specific antidote. Digoxin-specific Fab antibodies are effective in treating acute intoxications.23 A number of other plants contain cardiac glycosides including Nerium oleander, Thevetia peruviana, Convallaria majalis, Taxus brevifolia, Strophanthus spp., Acocanthera spp., and Urginea maritima.

Ephedra or ma huang

The dried young branches of ephedra (Ephedra spp.) have been used for their stimulating and vasoactive effects. In addition, ephedra has been used in several products promoted for weight loss. The plant constituents responsible for biological activity are the alkaloids ephedrine and pseudoephedrine. In commercial use, dried ephedra should contain no less than 1.25% ephedrine. Ephedrine and pseudoephedrine are sympathomimetics, and acute intoxication is associated with insomnia, restlessness, tachycardia, and cardiac arrhythmias. Nausea and emesis are also reported to occur. A case series involving intoxication of dogs following ingestion of a weight loss product containing guarana (caffeine) and ma huang (ephedrine) was recently reported.6 Estimated doses of the respective plants associated with adverse effects were 4.4 to 296.2 mg/kg and 1.3 to 88.9 mg/kg, respectively. Clinical signs included hyperactivity, tremors, seizures, behavioral changes, emesis, tachy-cardia, and hyperthermia. Ingestion was associated with mortality in 17% of the cases. North American species of ephedra (also called Mormon tea) have not been shown to contain any pharmacologically active alkaloids.

The use of ephedra in humans has been associated with a greatly increased risk for adverse effects compared with other commonly used herbs. One study reported that products containing ephedra accounted for 64% of all reported adverse effects from herbs, although they accounted for only 1% of herbal product sales.24 The actual frequency of adverse effects in patients using ephedra could not be determined since the study was based upon calls received by human poison control centers. However, based upon such studies the FDA initiated a ban on ephedra-containing products in April of 2004. This marked the first time that the FDA banned the sale of a dietary supplement since the passage of the DSHEA Act in 1994.

Garlic

Allium sativum is a member of the onion family. The plant contains 0.1% to 0.3% of a strong-smelling volatile oil containing allyl disulfides, such as allicin. Extracts from garlic are reported to have a number of biocidal activities, to decrease lipid and cholesterol levels, to prolong clotting times, to inhibit platelet aggregation, and to increase fibrinolytic activity.25,26 Acute toxicity of allicin for dogs and cats is unknown; its median lethal dose (LD50) for mice following subcutaneous or IV administration is 120 mg/kg and 60 mg/kg, respectively. Oral LD50s for garlic extracts given to rats and mice range from 0.5 mL/kg to 30 mL/kg. In chronic toxicity studies with garlic oil or garlic extracts, anemia has been observed in dogs. A single 25-mL dose of fresh garlic extract has caused burning of the mouth, esophagus and stomach, nausea, sweating, and lightheadedness.26 Topical application of garlic oil causes local irritation, which can be quite severe. The sensitivity of cat hemoglobin to oxidative damage may make cats more sensitive to adverse effects.

Guarana

Guarana is the dried paste made from the crushed seeds of Paullinia cupana or P. sorbilis, a fast-growing shrub native to South America. Currently the most common forms of guarana include syrups, extracts, and distillates used as flavoring agents and as a source of caffeine for the soft drink industry. More recently, it has been added to weight loss formulations in combination with ephedra. Caffeine concentrations in the plant range from 3% to 5%, which compares with 1% to 2% for coffee beans. Oral lethal doses of caffeine in dogs and cats range from 110 to 200 mg/kg body weight and 80 to 150 mg/kg body weight, respectively.27 See Ephedra for a discussion of a case series involving dogs ingesting a product containing guarana and ephedra.6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree