Chapter 22. Growth

GROWTH PATTERNS

By the time they reach their adult weight, most dogs and cats have increased their birth weight by fortyfold to fiftyfold. Enormous variation exists in the mature size, body type (conformation), body weight, coat type, and temperament of different breeds and types of dogs. For example, a 5-pound (lb) Chihuahua and a 150-lb Newfoundland both achieve complete development and growth within relatively similar periods of time. The thirtyfold difference in mature size between these two dogs means that the Newfoundland’s rate of growth and amount of tissue accretion far exceeds that of the Chihuahua. Such dramatic differences in body size and type are not observed in cats, which vary relatively little in mature size.

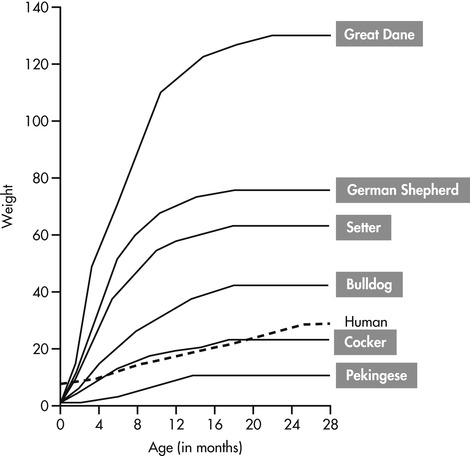

In both dogs and cats, the most rapid growth period occurs during the first 3 to 6 months of life. Patterns of growth differ among dog breeds of different sizes, with larger breeds experiencing a longer growth period than small breeds. While both large and small dogs show exponential growth rates during the first several months of life, this period of rapid growth is shorter in small breeds and ends earlier, at about 3 months of age. 1 Conversely, exponential growth continues for another month in large breeds and for another 2 months in giant breeds. Toy, small, and medium breeds of dogs attain adult body weight by approximately 9 to 10 months of age, while large and giant breeds attain adult weight when they are between 11 and 15 months old. 1. and 2. Although body weight stabilizes at these ages, development continues for several more months. Toy- and small-breed dogs and cats reach mature body size when they are between 9 and 12 months old, while the large and giant breeds of dogs are not typically considered to be mature until they are 18 to 24 months of age (Figure 22-1 and Figure 22-2). 3. and 4. Although the mature size of many breeds has changed since they were initially constructed, the growth curves shown in Figure 22-2 illustrate the relative growth rate differences among dog breeds of different sizes.

Large and giant dog breeds experience a longer growth and maturation period than the small and toy breeds. Although body weight stabilizes several months earlier, toy- and small-breed dogs and cats reach mature body size when they are between 9 and 12 months old. Body size and conformation of the large and giant breeds of dogs continue to develop until they are 18 to 24 months of age.

Dog breeds also differ in conformation. For example, breeds such as the Greyhound and Irish Wolfhound were developed to chase prey species while acting as hunting aids. The long legs, deep chest and relatively slender conformation of these breeds contributes to speed and agility. In contrast, other large breeds such as Mastiffs and Newfoundlands were selected for strength and endurance and have heavier body conformations that reflect their original working functions. Because different breeds of dogs have different rates of growth, mature weights, and body types, the food that is fed during growth should reflect these differences. In recent years, pet food companies have recognized these differences and have developed products that provide optimal nutrition for growing dogs of different mature sizes and weights, and in some cases different breeds. Although there is some evidence that growth patterns may differ among similarly sized breeds with differing body compositions, the most important nutritional distinction during growth is that observed between the large and giant breeds and small and toy breeds.

Large- and Giant-Breed Dogs

The genetic selection for breeds of dogs that have a large mature size has concurrently selected for the potential to grow very rapidly. Although the genetic potential for rapid growth is not in itself a health risk, feeding practices that allow maximal growth rate contribute to risk for developmental orthopedic diseases such as osteochondrosis, hypertrophic osteodystrophy and hip dysplasia. 5.6. and 7. The most important nutrient that affects growth rate is energy. Large-breed puppies that are overfed or fed energy-dense (high-fat) foods during periods of rapid growth are able to reach their maximum genetic growth potential. Growing at a rapid rate is incompatible with healthy skeletal development. For example, when Great Dane puppies were either allowed to eat ad libitum or were limit-fed to 60% to 70% of ad libitum intake, the dogs that were limit-fed grew more slowly and showed a dramatic reduction in skeletal abnormalities when compared with the ad libitum–fed dogs. 8 Conversely, controlling rate of growth supports healthy skeletal development. A longitudinal study with Labrador Retrievers found that dogs that were limit-fed to maintain a lean body condition grew at moderate rates and showed a reduced incidence and severity of hip dysplasia when compared with dogs that were fed ad libitum. 9

Although the underlying causes of developmental skeletal diseases are multifaceted and vary with the type of disorder, it is without question that excess energy intake and the resultant rapid growth rate in large dogs can contribute to aberrations in normal bone and cartilage development. During rapid growth, the bone that supports developing cartilage in joints becomes less dense and weaker than normal, causing the bone matrix to inadequately support the overlying joint cartilage. 10 The damaged cartilage surface, coupled with disturbances to the normal function and metabolism of cartilage-forming cells in the joint, lead to joint defects such as those seen in osteochondrosis. These changes are exacerbated by the mechanical stress of a heavier body weight on the developing skeleton. Similarly, increased weight bearing on developing hips and a growth disparity between soft tissue and skeletal tissue are considered to be factors in the development of canine hip dysplasia (for a complete discussion, see Chapter 37, pp. 491-494).

In addition to the food’s energy density, another nutrient that is important for skeletal health in large and giant breeds is calcium. Active calcium absorption mechanisms are not fully mature in growing puppies until they are about 6 months of age. 11. and 12. Prior to this age, up to 70% of the calcium that is absorbed from the diet enters the body through passive absorption in the small intestine. Because passive absorption cannot be down-regulated, the amount of calcium that is absorbed is directly proportional to its concentration in the diet. 13 Active absorption is functional in growing puppies, but cannot effectively down-regulate in response to excess dietary calcium. As a result, puppies are unable to protect themselves from absorbing excess (and unneeded) calcium when it is present in the diet. As puppies mature, active absorption mechanisms become tightly regulated through the actions of vitamin D 3, parathyroid hormone, growth hormone, and calcitonin. 14 Together, these hormones tightly regulate the amount of calcium that is absorbed, protecting the older puppy from excessive calcium uptake. However, the time at which the body’s calcium absorption mechanisms mature is too late to protect puppies from excessive dietary calcium uptake during the most rapid growth period between 3 and 5 months of age. As a result, puppies from weaning to 6 months are highly susceptible to excessive dietary calcium and its effects on the developing skeleton.

Several studies have shown that an excessive level of dietary calcium or supplementation with this mineral during the rapid growth period negatively affects skeletal development in large breeds of dogs (most frequently, Great Danes). 6.12. and 15. Great Dane puppies fed a food containing 3.3% calcium from weaning until 6 months of age showed an increased incidence of osteochondritic lesions when compared with puppies fed a food that contained 1.1% calcium. 16 Interestingly, although small and medium breeds of dogs have the same patterns of passive and active calcium absorption during growth, these breeds are not as susceptible to developmental skeletal disease when exposed to dietary calcium excess. 17. and 18. Neither do all large and giant breeds respond as dramatically to excess dietary calcium as do Great Danes. There is some evidence that such differences may be related to genetic differences among breeds in calcium uptake and metabolism early in life. 19 Regardless of possible differences among breeds, including more calcium than the body needs, either through diet or supplementation, is unnecessary and poses significant risk for the development of several types of skeletal disease in large- and giant-breed dogs (for a complete discussion, see Chapter 37, pp. 497-500).

Two other nutrients that are of interest when feeding large-breed dogs during growth are protein and vitamin D. Although high protein intake was identified as a potential contributor to rapid growth rate in early studies, it was subsequently discovered that the apparent protein effect was actually caused by excess energy intake and was not related to the protein level in the food. When growing Great Dane puppies were fed foods that had identical caloric densities (3600 kilocalories (kcal) metabolizable energy/kilogram (ME/kg) but varied in protein content (31.6%, 23.1%, or 14.6%), dietary protein did not affect skeletal development. 20 However, the lowest protein diet (14.6%) was not sufficient to promote optimal growth and health. Although it is important that adequate level of protein is provided and that protein level is balanced with the food’s energy density, protein by itself does not negatively affect growth rate or skeletal development in large-breed dogs.

Because of its role in calcium metabolism and homeostasis, the impact of dietary vitamin D on skeletal development in dogs has been examined in recent years. 21 As discussed in Chapter 13 (pp. 108-110), dogs and cats require a dietary source of vitamin D 3 (cholecalciferol) because they are unable to produce adequate amounts of the vitamin from its precursor, 7-dehydrocholesterol, found in skin. Dietary vitamin D 3 is converted to 24-dihydroxycholecalciferol in the liver. Blood concentrations of this metabolite closely parallel dietary intake. 24-dihydroxycholecalciferol is converted in the kidney into one of the two biologically active forms of vitamin D; 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol or 24,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol. The biologically active forms of vitamin D influence calcium homeostasis by regulating calcium absorption in the intestine and resorption in the kidney, and bone formation and resorption. The first compound, 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol, is recognized as the most biologically active form and exerts its effects on all three tissues (intestine, kidney, and bone). The less active form, 24,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol, works principally at the skeletal level to promote the formation of new bone. As a species, dogs are relatively tolerant of excess dietary vitamin D 3 and possess effective mechanisms to maintain normal calcium homeostasis even when fed excess levels of the vitamin during growth. 22. and 23. However, Great Dane puppies raised on foods containing nontoxic but excess concentrations of vitamin D 3 (10- and 100-fold greater than recommended levels) developed abnormal changes to growth plates and skeletal remodeling, even though they maintained normal calcium homeostasis. 24 The higher concentration caused the development of radius curvus syndrome in some dogs. These changes were not caused by calcium, but rather by a direct effect of vitamin D 3 on developing growth plates.

It was theorized that differences in vitamin D metabolism may exist between large- and small-breed dogs. Studies to test this found that concentrations of 24,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol in the plasma of growing large-breed dogs (Great Danes) were significantly lower than the levels observed in small-breed puppies (Miniature Poodles). 14 Concentrations in the Great Danes were found to be negatively correlated with the activity of growth hormone. 25 Great Dane puppies also had lower plasma levels of 25-dihydroxycholecalciferol and slightly lower 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol levels. Despite these differences, intestinal absorption of calcium did not differ between the two breeds of puppies; however, Great Dane puppies showed irregularities in growth plate development that were not seen in the Poodle puppies. 26 Differences in vitamin D 3 metabolism between large and small breeds may be another factor that influences an individual dog’s susceptibility to developmental skeletal disease. Further studies are needed to examine effects of different levels of dietary vitamin D on the production of biologically active vitamin D metabolites during growth in large and small breeds, and the effects on the developing skeleton. Currently, commercial dog foods contain vitamin D 3 (cholecalciferol) to supply the needed source of this vitamin since dogs cannot produce cholecalciferol from 7-dehydrocholesterol in the skin. Additional research may support adjustments in these levels with enhanced understanding of its role in skeletal health in growing large-breed dogs.

Multiple factors, including genetics and husbandry practices, influence a dog’s risk for developing skeletal disease. Breeders can help to reduce the incidence of developmental skeletal disease through careful screening and selection of breeding animals. In addition, feeding an appropriate diet and using proper feeding practices throughout the growth period reduces risk and supports healthy skeletal growth (see pp. 231-233). The time period that is of greatest importance is the period of rapid growth, between 3 and 5 months of age. An appropriate food for large- and giant-breed puppies has reduced fat and energy density, a balanced level of high-quality protein that is adjusted to energy density, and a level of calcium and phosphorus that is slightly less than that found in puppy foods intended for small breeds of puppies. A recommended nutrient profile for a growth diet formulated for large and giant breeds is one that contains 26% to 28% protein, 14% to 16% fat, 0.8% to 0.9% calcium, 0.6% to 0.8% phosphorus, and a caloric density between 360 and 400 kcal per cup. 27 Feeding practices are equally important. Puppies should be meal-fed two or three times daily, and portions should be premeasured. Limit-feeding should be closely adjusted to maintain a lean, not plump, body condition, throughout growth (see pp. 231-233). Although rate of growth will be lower than that of a dog who is fed a more energy-dense food, ultimate adult size will not be compromised and risk of skeletal disease will be reduced (Table 22-1).

| HOD, Hypertrophic osteodystrophy. | ||||

| N utrient | E ffect of nutrient level on skeletal development | N utritional recommendation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L ow | M edium | H igh | ||

| Protein | Decreased growth rate (if deficient) | Normal growth rate | Normal growth rate | 26%-28% |

| Energy | Decreased growth rate (if deficient) | Normal growth rate | Increased growth rate and risk of skeletal disease | 360-400 kcal/cup |

| Calcium | Decreased growth rate Decreased bone mineral content and strength | Increased bone mineral content and strength Proper conformation Reduced risk of HOD | Increased bone mineral content and strength Poor conformation Increased risk of HOD | 0.8%-0.9% (Ca:P ratio = 1.2:1) |

Large and giant breeds of dogs have the potential to grow very rapidly during their first 6 months of life. However, allowing these dogs to achieve their genetic potentials for growth rate is not compatible with healthy skeletal development. An appropriate food for large- and giant-breed puppies has reduced fat and energy density, a balanced level of high-quality protein that is adjusted to energy density, and a level of calcium and phosphorus that is slightly less than that found in puppy foods intended for small breeds of puppies.

Small- and Toy-Breed Dogs

Dogs of the small and toy breeds have higher energy requirements per unit of body weight than do the large and giant breeds. This occurs because basal metabolic rate is related to total body surface area. Small and toy breeds have higher ratios of surface area to body weight than do large breeds and so have higher energy needs per unit of weight (lb or kg). In addition to their relatively high energy needs, small breeds of puppies also have small stomachs that hold limited amounts of food. A dog food formulated for growing small and toy breeds should be higher in energy and nutrient density than a food formulated for large dogs, and it should contain ingredients that are highly digestible and available. The size and shape of the kibble pieces should be designed for small mouths to facilitate easy chewing and consumption.

Small- and toy-breed puppies should be fed foods that are higher in energy (and nutrient) density than foods designed for large-breed puppies. The food should also contain ingredients that are highly digestible and available, and kibble pieces should be small enough for small mouths.

NUTRIENT NEEDS DURING GROWTH

Energy

For all dogs and cats, regardless of size or breed, nutrient and energy needs during growth exceed those of any other stage of life except lactation. During the period of rapid growth the energy needs of growing puppies are approximately twice those of adult dogs of the same size. After 6 months of age, these needs begin to decline as growth rate decreases. After weaning, growing puppies require approximately twice the energy intake per unit of body weight as adult dogs of the same weight. 28 When puppies reach about 40% to 50% of their adult weight, this requirement declines to about 1.6 times maintenance levels. When 80% of adult weight is achieved, energy needs are approximately 1.2 times maintenance levels. As discussed previously, the age at which a puppy will attain these proportions of adult weight will vary with the adult size of the dog. Although all puppies grow most rapidly when they are between 3 and 5 months of age, large breeds of dogs reach maturity at a later age than do small breeds. 1 With the exception of the giant breeds, most puppies achieve 40% of their adult weight between 3 and 4 months of age and 80% of adult weight between 4 ½ and 8 months. Very large breeds of dogs do not attain adult size until they are 10 months of age or older. 29 General guidelines for determining energy needs for growing dogs are provided in Table 22-2.

| ME, Metabolizable energy. | ||

| A ge | A djustment factor(× adult ME) | E xample |

|---|---|---|

| Small and medium breeds | ME requirement = 130 × W kg0.75 | |

| Weaning to ∼4 months | 2 | 7-lb puppy: [2 × (130 × 3 0.75)] = 590 kcal/day |

| 4-6 months | 1.6 | 16-lb puppy: [1.6 × (130 × 7.3 0.75)] = 923 kcal/day |

| 6-10 months | 1.2 | 22-lb puppy: [1.2 × (130 × 10 0.75)] = 877 kcal/day |

| ∼10-12 months | 1 (Adult) | 26-lb dog: 130 × 11.8 0.75 = 827 kcal/day |

| Large and giant breeds | ||

| Weaning to ∼4 months | 2 | 16-lb puppy: [2 × (130 × 7.3 0.75)] = 1151 kcal/day |

| 4-8 months | 1.6 | 34-lb puppy: [2 × (130 × 15.4 0.75)] = 1617 kcal/day |

| 9 to ∼12 months | 1.4 | 52-lb puppy: [(1.4 × (130 × 23.6 0.75)] = 1948 kcal/day |

| ∼12-18 months | 1.2 | 58-lb dog: [(1.2 × (130 × 26.4 0.75)] = 1815 kcal/day |

| 18-24 months | 1 (Adult) | 64-lb dog: 130 × 29 0.75 = 1624 kcal/day |

Similarly, growing cats have energy needs that are significantly higher than are the maintenance needs of adult cats. The energy and nutrient requirements of growing kittens are highest per unit of body weight at about 5 weeks of age. Young, rapidly growing kittens require approximately 200 to 250 kcal of ME per kg of body weight. This requirement declines to 130 kcal/kg by 20 weeks of age and to 100 kcal/kg by 30 weeks of age. An example of energy needs for a growing kitten is provided in Table 22-3.

| A ge | kcal/kg body weight | E xample |

|---|---|---|

| 6-20 weeks | 250 | 3-lb kitten: 250 × 1.4 = 350 kcal/day |

| 4-6½ months | 130 | 5-lb kitten: 130 × 2.3 = 299 kcal/day |

| 7-8½ months | 100 | 6-lb kitten: 100 × 2.7 = 270 kcal/day |

| 9-11 months | 80 | 7-lb kitten: 80 × 3.2 = 256 kcal/day |

| 12 months | 60 | 7.5-lb cat: 60 × 3.4 = 204 kcal/day |

Protein

The protein requirement of growing puppies and kittens is higher than the protein requirement of adult animals. In addition to normal maintenance needs, young animals also need more protein to build the new tissue that is associated with growth. Because young animals consume higher amounts of energy and thus higher quantities of food than adult animals, the total amount of protein that they consume is naturally higher. Pet foods fed to growing puppies and kittens should contain slightly higher protein levels than foods developed for maintenance only. More importantly, the protein included in the diet should be of high quality and highly digestible. This type of protein ensures that sufficient levels of all of the essential amino acids are being delivered to the body for use in growth and development. The actual percentage of protein in the diet is not as important as is the balance between protein and energy. The minimum proportion of energy that should be supplied by protein in foods for growing dogs is 22% of the ME kcal, and the minimum for growing cats is 26%. 30 Optimal levels are between 25% and 29% of ME kcal for puppies and 30% and 36% for kittens. As discussed previously, the percentage of protein in foods formulated for growing large- and giant-breed dogs will be slightly lower (∼26%) than the percentage of protein found in foods for small- and medium-breed puppies because of the lower energy content and the need to balance protein with energy.

To support the growth of new tissues, foods for growing puppies and kittens should have slightly higher protein content than foods formulated for adult maintenance. The protein in the food should be of high quality and levels must be adjusted to be balanced with the food’s energy density.

Calcium and Phosphorus

Diets for growing dogs and cats should contain optimal, but not excessive, amounts of calcium and phosphorus. The Association of American Feed Control Officials’s (AAFCO’s) Nutrient Profiles recommends that dog and cat foods formulated for growth contain a minimum of 1% calcium and 0.8% phosphorus on a dry-matter basis (DMB). 30 These recommendations are based upon diets containing 3500 and 4000 kcal/kg. Some commercially available pet foods contain slightly more than the recommended levels of calcium and phosphorus. These levels are not considered excessive but might not be optimal for large- and giant-breed dogs during periods of rapid growth. Growth diets formulated for large breeds should contain lower percentages of calcium and phosphorus because of the lower energy densities of these diets and the need to carefully control calcium intake to support proper skeletal development. Dietary calcium and phosphorus supplements should never be added to a balanced, complete food that has been formulated for growing dogs or cats (see Section 5, pp. 497-500).

Contrary to popular belief, calcium and phosphorus supplements are not necessary for growing pets and can be harmful in large and giant breeds of dogs, contributing to the development of certain developmental skeletal disorders.

Docosahexaenoic Acid

Long-chain n-6 and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFAs) are essential early in life for normal neurological development (see Chapter 11, pp 84-85 and Chapter 21, p. 211). The two fatty acids of greatest significance are arachidonic acid (AA), derived from linoleic acid, and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), derived from alpha-linolenic acid. Both of these fatty acids are essential during perinatal life; DHA is especially crucial for normal neurological and retinal development. 31. and 32. In human fetuses, AA and DHA rapidly accumulate in brain and retinal tissues during the latter half of gestation and together make up approximately 50% of the total fatty acids found in the brain’s grey matter. 33 The analogous period of brain growth and maturation in puppies occurs between 1 and 60 days of age. 34 Both a prenatal and postnatal supply of DHA is considered to be essential for puppies and kittens. 35.36. and 37.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree