Oesophagus (see8.14, 8.15, 8.16, 8.17, 8.18, 8.19 and 8.20)

Stomach268

10.1 Normal radiographic appearance of the stomach268

10.2 Displacement of the stomach269

10.3 Variations in stomach size269

10.4 Variations in stomach contents270

10.5 Variations in the stomach wall271

10.6 Gastric contrast studies: technique and normal appearance272

10.7 Technical errors on the gastrogram273

10.8 Gastric luminal filling defects on contrast studies273

10.9 Abnormal gastric mucosal pattern on contrast studies274

10.10 Variations in gastric emptying time274

10.11 Ultrasonographic technique for the stomach275

10.12 Normal ultrasonographic appearance of the stomach276

10.13 Variations in gastric contents on ultrasonography276

10.14 Lack of visualization of the normal gastric wall layered architecture on ultrasonography277

10.15 Focal thickening of the gastric wall on ultrasonography277

10.16 Diffuse thickening of the gastric wall on ultrasonography277

Small intestine277

10.17 Normal radiographic appearance of the small intestine277

10.18 Variations in the number of small intestinal loops visible278

10.19 Displacement of the small intestine278

10.20 Bunching of small intestinal loops278

10.21 Increased width of small intestinal loops279

10.22 Variations in small intestinal contents280

10.23 Small intestinal contrast studies: technique and normal appearance282

10.24 Technical errors with small intestinal contrast studies282

10.25 Variations in small intestinal luminal diameter on contrast studies283

10.26 Small intestinal luminal filling defects on contrast studies283

10.27 Variations in the small intestinal wall on contrast studies283

10.28 Variations in small intestinal transit time on contrast studies284

10.29 Ultrasonographic technique for the small intestine285

10.30 Normal ultrasonographic appearance of the small intestine285

10.31 Variations in small intestinal contents on ultrasonography285

10.32 Dilation of the small intestinal lumen on ultrasonography285

10.33 Lack of visualization of the normal small intestinal wall layered architecture on ultrasonography285

10.35 Focal thickening of the small intestinal wall on ultrasonography286

10.36 Diffuse thickening of the small intestinal wall on ultrasonography287

10.37 Mucosal layer alterations of the small intestine287

Large intestine287

10.38 Normal radiographic appearance of the large intestine287

10.39 Displacement of the large intestine288

10.40 Large intestinal dilation289

10.41 Variations in large intestinal contents289

10.42 Variations in large intestinal wall opacity290

10.43 Large intestinal contrast studies: technique and normal appearance290

10.44 Technical errors with large intestinal contrast studies291

10.45 Large intestinal luminal filling defects on contrast studies291

10.46 Increased large intestinal wall thickness on contrast studies291

10.47 Abnormal large intestinal mucosal pattern on contrast studies291

10.48 Ultrasonographic technique for the large intestine292

10.49 Normal ultrasonographic appearance of the large intestine292

10.50 Ultrasonographic changes in large intestinal disease292

STOMACH

10.1. NORMAL RADIOGRAPHIC APPEARANCE OF THE STOMACH

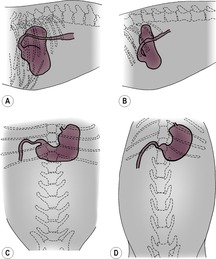

The stomach consists of a fundus (dome-like outpouching dorsally on the left), cardia (junction with the oesophagus), body (middle portion) and pyloric portion (pyloric antrum and canal ventrally on the right). An imaginary line joining the fundus, body and pylorus is known as the gastric axis. The position of the stomach differs between dogs and cats and between conformational types of dog. In cats and in most breeds of dog, the gastric axis lies parallel to the caudal ribs on the lateral view, against the liver, and so displacement of the stomach axis reflects a change in liver size or position (Fig. 10.1A and B). In deep-chested dog breeds, the gastric axis is perpendicular to the spine, and this may mimic reduced liver size. The pylorus may lie slightly cranial to the rest of the stomach, and its position and appearance vary slightly between right and left lateral recumbency. In right lateral recumbency, the pylorus is likely to be fluid-filled and appears as a round soft tissue mass; in left lateral recumbency it may contain gas, which may extend into the descending duodenum. Gas rises to the uppermost portion of the stomach and fluid pools in the dependent part, so positional radiography may be used to highlight certain areas with gas, for example left lateral recumbency to assess pyloric and proximal duodenal pathology such as mural masses and foreign bodies. In deep-chested dog breeds, on the ventrodorsal (VD) view the gastric axis lies transversely approximately at the level of the tenth intercostal space, with the fundus to the left and the pylorus to the right of the midline (Fig. 10.1C). In barrel-chested breeds, the stomach is more curved, with the fundus lying more cranially and the pylorus closer to the midline. In cats, on the VD view an empty stomach is located with the pylorus in the midline and the remainder of the stomach to the left side (Fig. 10.1D). Distension of the feline stomach results in displacement of the pylorus to the right side. The amount of air or ingesta present combined with normal gastric contractions will affect the size and shape of the stomach, and opacity depends on the nature of the gastric contents.

10.2. DISPLACEMENT OF THE STOMACH

4. Stomach displaced towards the right.

a. Enlarged spleen.

b. Left-sided liver enlargement.

5. Stomach displaced towards the left.

a. Enlarged pancreas, particularly body.

b. Right-sided liver enlargement.

The stomach may also be variably displaced in cases of gastric dilation and volvulus (GDV); chronic gastric volvulus without dilation is also seen, in which the stomach is in an abnormal location but is not markedly distended.

10.3. VARIATIONS IN STOMACH SIZE

A small amount of gas and/or fluid is normally observed in the stomach after an 8 h fast.

1. Stomach not visible.

a. Completely empty.

b. Absence of abdominal fat.

– Young animals.

– Emaciation.

c. Peritoneal effusion.

2. Stomach visible but empty.

a. Fasted or anorexic (NB: this does not rule out obstruction if the animal has vomited recently).

3. Stomach normal shape and size; gas and/or fluid contents.

a. Normal, with some aerophagia.

b. Recent drink.

c. Acute gastritis.

4. Stomach distended but normal in shape. The fundus and body tend to enlarge more than the pylorus and do so mainly on the left side of the abdomen.

a. Endotracheal tube in oesophagus not trachea – dilation with gas.

b. Excessive ingestion of food.

c. Acute dilation by air and/or fluid.

– Aerophagia due to dyspnoea.

– Aerophagia secondary to any painful condition such as pancreatitis or blunt trauma.

– Acute gastritis.

– Outflow obstructed by a foreign body.

– After abdominal surgery.

– Anticholinergic drugs.

– After endoscopy.

d. Chronic dilation – may show a gravel sign (see 10.4.2 and Fig. 10.3).

– Chronic obstruction by foreign bodies in the stomach or duodenum.

– Pyloric outflow problem (see 10.10.3).

e. Pancreatitis.

f. Dysautonomia – may also see small intestinal, oesophageal and urinary bladder dilation.

5. Stomach distended with an abnormal shape.

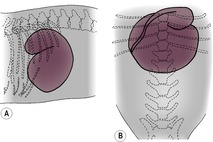

a. Gastric dilation and volvulus (Fig. 10.2) – especially in large, deep-chested dogs. The stomach will be abnormally distended by food, liquid and gas, with the stomach lumen apparently divided into two by a soft tissue band, giving a double-gas bubble appearance, also known as compartmentalization or a boxing glove sign. This is due to the soft tissue of the lesser curvature and proximal duodenum coursing caudally from their abnormal position in the craniodorsal quadrant of the abdomen. Frequently, the pylorus will be displaced dorsally and towards the left side; the fundus will be displaced ventrally and towards the right side unless the degree of rotation approaches 360°. It is helpful to perform both right and left lateral recumbent radiographs, as gas will move around in the stomach and may help to identify the position of the pylorus. Other signs of GDV include splenic displacement, ileus, pneumatosis (intramural gas), pneumoperitoneum and megaoesophagus. GDV is rare in cats and is usually associated with diaphragmatic rupture.

b. Acute dilatation with gas or food in a dog that previously had a gastropexy – the stomach will fold on itself, resulting in an abnormal, boxing glove appearance.

Radiography is not necessary to diagnose severe gastric dilation but is invaluable in detecting volvulus, because easy passage of a stomach tube does not rule out rotation.

10.4. VARIATIONS IN STOMACH CONTENTS

The animal should ideally be fasted for 12h prior to elective abdominal radiography. Retention of food in the stomach after 12h is usually abnormal; however, sometimes the animal eats unknown to the owner during the fast, so the radiographs should be repeated under a more controlled fasting situation. Obtaining radiographs with the animal in different positions may be helpful in outlining abnormal stomach contents, as gas rises to the highest part of the stomach.

1. Small amount of gas and/or fluid – normal.

2. Mineral opacity material.

a. Foreign bodies (sometimes incidental findings in dogs).

– Metallic materials such as fish hooks, needles and staples.

– Stones, pebbles, etc.

– Bones or bone fragments; differential diagnosis is mineralization of rugal folds secondary to chronic renal failure.

– Dense rubber or glass.

c. Barium from a previous contrast study.

d. Medications containing bismuth and kaolin.

e. Mimicked by mineralization of the stomach wall (see 10.5.3).

3. Soft tissue radiopacity with interspersed small gas bubbles.

a. Food – normal if not fasted.

b. Abnormal retention of food if fasted for more than 12h (e.g. due to outflow obstruction to the pylorus and/or duodenum, or nervous pylorospasm if hospitalized).

c. Foreign bodies.

– Plastic or cellophane.

– Fabrics, carpet or string.

– Phytobezoar (e.g. grass).

– Trichobezoar (e.g. hairball).

4. Uniform soft tissue radiopacity.

a. Recently ingested liquid.

b. Retained liquids.

– Acute gastric dilation.

– Outflow obstruction of the pylorus and duodenum.

c. Foreign bodies.

d. Large gastric tumour or polyp.

e. Blood clot.

f. Pylorogastric (gastrogastric) or duodenogastric intussusception – rare, as intussusceptions are more often in the aboral than the oral direction.

6. Homogeneous, grey-appearing stomach content is usually due to equal amounts of water and fluid content superimposed.

10.5. VARIATIONS IN THE STOMACH WALL

The gastric wall thickness can be evaluated accurately only when the stomach is moderately distended by gas or radiopaque contrast medium (see 10.6). Rugal folds are predominantly located in the fundus and are smaller and more numerous in dogs than in cats. Few rugal folds are observed in the pyloric antral region.

1. Focally thickened stomach wall.

a. Pseudomass.

– Transient wall contraction of an empty stomach.

– Fluid accumulation in pylorus in right lateral recumbency.

b. Neoplasia (Fig. 10.4), often associated with localized poor distension and lack of peristalsis.

– Adenocarcinoma – usually lesser curvature and pylorus; Staffordshire Bull Terrier, Rough Collie and Belgian Shepherd dog predisposed.

– Leiomyoma or leiomyosarcoma.

– Lymphoma (especially cats).

c. Pyloric muscular or mucosal hypertrophy.

d. Polyp.

e. Focal chronic hyperplastic gastropathy (syn. giant hypertrophic gastritis, Ménétrier’s disease); unlike neoplasia, the stomach wall remains mobile.

f. Focal infiltrative gastritis.

– Eosinophilic.

– Granulomatous.

– Fungal infections, especially Pythium insidiosum*.

g. Aberrant Spirocerca lupi* granuloma.

2. Diffusely thickened stomach wall.

a. Secondary to persistent vomiting.

b. Chronic gastritis.

c. Eosinophilic gastritis.

d. Lymphoma (especially cats).

e. Non-beta tumour of pancreas (gastrinoma or APUDoma) due to trophic effect on gastric mucosa causing rugal fold hypertrophy.

f. Chronic hyperplastic gastropathy.

g. Fungal infections, especially Pythium insidiosum*.

3. Mineralization of the stomach wall.

a. Mimicked by mineralized stomach contents (see 10.4.2).

b. Artefactual due to the presence of linear gastric foreign bodies.

c. Rugal fold mineralization.

– Uraemic gastropathy, due to renal secondary hyperparathyroidism.

– Other causes of severe hypercalcaemia, especially toxicity with vitamin D and analogues (e.g. cholecalficerol rodenticide, calcipotriol in antipsoriasis cream).

d. Dystrophic mineralization in masses.

– Neoplasm.

– Granuloma (e.g. Pythium insidiosum*, aberrant Spirocerca lupi* granuloma, which may also undergo neoplastic transformation).

4. Gas in the stomach wall (gastric pneumatosis).

a. Gastric ulceration.

b. Partial gastric wall perforation.

c. Necrosis secondary to GDV.

d. Secondary to pancreatitis.

5. Fat layer in the stomach wall.

a. May be seen in normal cats.

10.6. GASTRIC CONTRAST STUDIES: TECHNIQUE AND NORMAL APPEARANCE

Indications for contrast studies of the stomach include the following:

• Position of the stomach, including assessment of liver size and investigation of an unidentified abdominal mass.

• Orientation of the stomach (e.g. chronic torsion).

• Presence and location of suspected gastric foreign bodies.

• Vomiting, especially haematemesis.

• Melaena.

• Weight loss with possible gastric cause.

• Assessment of stomach wall thickness and mucosal pattern.

• Assessment of gastric emptying.

Pneumogastrography is a useful, simple and safe technique that is helpful for space-occupying diseases but gives no information about the mucosal surface, for which positive and double-contrast studies are required. If rupture of the stomach is suspected, low-osmolarity iodinated contrast medium rather than barium should be used. Following administration of contrast medium, fluoroscopy may be helpful to identify areas of poor gastric wall motility associated with neoplasia.

If the procedure is elective, preparation should involve a fast of at least 12h and appropriate chemical restraint. Radiographs should be taken in right lateral, left lateral, sternal and dorsal recumbency. The exposure factors used should be reduced following administration of air and increased with positive contrast media.

Pneumogastrogram

Pass a stomach tube and inflate the stomach with room air. Shows:

• Stomach location.

• Radiolucent foreign bodies and intraluminal masses.

• Stomach wall thickness.

• Little or no information about the mucosal surface.

Positive contrast gastrogram

a. Small-volume barium sulphate or iodinated contrast medium: shows stomach location.

b. Barium-impregnated polyethylene spheres (BIPS): gives some information about stomach emptying.

c. Large-volume (7–12mL/kg) 30% w/v barium sulphate using a stomach tube or 2–3mL/kg isotonic iodinated contrast medium. Shows:

– Stomach size.

– Stomach shape.

– Contractility.

– Contents (as filling defects).

– Liquid phase of stomach emptying.

d. Large-volume food studies (barium or BIPS mixed in food). Shows the solid phase of stomach emptying.

Double-contrast gastrogram

First, 1mL/kg barium 100% w/v is given by stomach tube, then the stomach is distended with air. Shows:

• Excellent mucosal detail.

• Stomach wall thickness.

• Radiolucent foreign bodies.

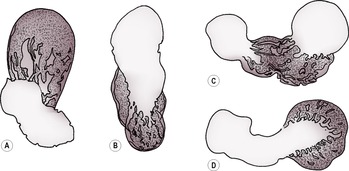

The normal gastrogram (Fig. 10.5) shows positive contrast medium pooling in dependent areas and luminal gas uppermost. Positive contrast medium in the inter-rugal clefts creates gently curving lines when seen en face and a serrated margin to the stomach when seen tangentially. On a correctly exposed radiograph of a patient in reasonable body condition, the thickness of the stomach wall can be assessed. Peristaltic waves create symmetrical, smooth indentations to the shape of the stomach, varying from image to image. The stomach should distend appropriately for the amount of filling, and poor distension suggests neoplasia or severe gastritis.

10.7. TECHNICAL ERRORS ON THE GASTROGRAM

1. Lack of plain (survey) radiographs.

a. Radiopaque foreign bodies overlooked.

b. Incorrect exposure factors used for the contrast study.

c. Patient not adequately fasted.

2. Inappropriate exposure factors – add 5–10kVp to settings used to obtain plain radiographs for positive contrast studies.

a. Underexposed positive contrast studies will hinder detection of smaller radiolucent foreign bodies.

b. Overexposed pneumogastrogram will hinder detection of smaller radiopaque foreign bodies.

3. Inadequate distension of the stomach.

a. Precludes accurate evaluation of wall thickness and of masses.

b. Results in a longer gastric emptying time, as inadequate distension fails to stimulate emptying reflexes.

4. Too much positive contrast used – small foreign bodies will be ‘drowned’; later radiographs should be taken to look for residual contrast adhering to foreign material.

5. Inadequate number of images (in absence of fluoroscopic examination) – may preclude the detection of gastric wall stiffness, foreign bodies, soft tissue masses and ulceration.

6. Over-diagnosis based on single or few images – mural lesions must be confirmed on multiple radiographs, as peristaltic waves lead to transient gastric wall thickening, which may give rise to false positive diagnoses.

10.8. GASTRIC LUMINAL FILLING DEFECTS ON CONTRAST STUDIES

Smaller foreign bodies may be hidden by large-volume positive gastrograms. See also 10.4, Variations in stomach contents.

2. Phytobezoar (e.g. grass) or trichobezoar (e.g. hairball).

3. Foreign bodies.

4. Stomach wall masses projecting into the lumen.

a. Neoplasm.

b. Polyp.

c. Granuloma.

d. Abscess.

e. Haematoma.

f. Pylorogastric (gastrogastric) or duodenogastric intussusception.

g. Chronic hyperplastic gastropathy (syn. giant hypertrophic gastritis, Ménétrier’s disease).

5. Blood clots and mucus.

10.9. ABNORMAL GASTRIC MUCOSAL PATTERN ON CONTRAST STUDIES

Mild ulcerative gastritis and shallow ulcers may be difficult to detect; consider using endoscopy instead, because normal radiographs do not rule out disease. The mucosal pattern is normally of parallel bands of barium in the inter-rugal clefts, with rugae seen as parallel-sided, band-like filling defects. Rugae are sparse near the pylorus and are less obvious in cats than in dogs.

1. Normal variant – the presence of ingesta or mucus creates an irregular, patchy rugal fold pattern mimicking pathology (flocculation).

2. Gastritis – irregular, patchy rugal fold pattern (Fig. 10.6); barium persists after the stomach has largely emptied, as it adheres to inflamed or ulcerated areas.

3. Ulceration – crater-like in profile and circular when seen en face (Fig. 10.7). Barium persists in the ulcer crater long after stomach has emptied (12 to 24 h films are therefore useful) and rugal folds may be gathered towards the ulcer.

a. Drugs.

– Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g. aspirin and ibuprofen).

b. Neoplasia.

– Primary gastric (e.g. adenocarcinoma and lymphoma).

– Pancreatic gastrinoma.

c. Secondary to mast cell tumours elsewhere.

d. Stress.

e. Inflammatory bowel disease.

f. Secondary to chronic hepatic and renal disease.

g. Due to the presence of abrasive foreign material.

4. Chronic hyperplastic gastropathy – greatly enlarged rugal folds; may cause secondary pyloric stenosis.

10.10. VARIATIONS IN GASTRIC EMPTYING TIME

Scintigraphy is considered the method of choice for assessment of gastric emptying, because radiography is less likely to represent normal physiological conditions. The use of ultrasonography has also been described. Factors affecting the passage of radiographic contrast media through the gut include the following:

• period of prior fasting

• use and nature of chemical restraint

• degree of relaxation of the patient

• type of contrast medium used

• quantity of contrast medium administered.

If the stomach was empty prior to administration of the contrast medium, barium suspensions should begin to exit within 30min in the dog and 15min in the cat (provided an adequate quantity was given), and the stomach should be completely empty by 4h in the dog and 2h in the cat. Hypertonic iodine solutions empty faster, as they induce hyperperistalsis. Barium mixed with food (or food alone) empties more slowly, taking up to 12h to empty completely. When food and BIPS are fed together, half the BIPS should have left the stomach by 6h (± 3h) and three-quarters by 8.5h (± 2.75h). Radiographs made 12–24h after barium administration may show a barium-outlined or impregnated ulcerative lesion or foreign body causing partial obstruction.

Fluoroscopy with image intensification is an invaluable method of assessing gut motility. In the absence of fluoroscopy, it may also be possible to detect presence or absence of peristalsis on serial radiographs.

1. Rapid gastric emptying.

a. Normal variant – liquid contrast medium given on an empty stomach.

b. Gastric emptying time is shorter in puppies than in adult dogs.

c. Gastroenteritis.

2. Delayed gastric emptying with decreased gastric motility (seen with fluoroscopy or on serial radiographs).

a. Sedation or general anaesthesia, or use of spasmolytics.

b. Gastric or duodenal ulceration.

c. Gastritis.

– Parvovirus.

– Cats – panleucopenia.

d. Small intestinal obstruction.

e. Pancreatitis.

f. Peritonitis.

g. Hypokalaemia due to vomiting.

h. Dysautonomia – may also see small intestinal, oesophageal and urinary bladder dilation.

3. Delayed gastric emptying with normal or increased gastric motility.

a. Diet – fatty food takes longer to exit stomach.

b. Pyloric obstructions and stenoses (Fig. 10.8).

– Foreign bodies.

– Pyloric muscular or mucosal hypertrophy.

– Pyloric, duodenal, pancreatic or gall bladder neoplasia.

– Pyloric or duodenal scar tissue.

– Pyloric or duodenal ulceration.

– Pyloric or duodenal granuloma.

– Pyloric or duodenal polyp.

– Chronic hyperplastic gastropathy; large rugal folds.

– Idiopathic – especially Siamese cats, and may be associated with megaoesophagus.

c. Pylorospasm.

– Nervous pylorospasm.

– Small intestinal obstruction.

10.11. ULTRASONOGRAPHIC TECHNIQUE FOR THE STOMACH

The patient should ideally be fasted for 12h prior to ultrasonographic examination of the stomach but allowed free access to water. The presence of food or gas in the stomach will result in artefacts preventing complete examination of the gastric lumen and wall. Water administered by stomach tube at 10–15mL/kg will enhance visibility of mural pathology.

A sector or curvilinear transducer of as high a frequency as possible compatible with adequate tissue penetration should be used (7.5MHz in cats or small or medium dogs; 5MHz in large or obese dogs). Endoscopic ultrasonography is especially useful but is still not widely available in veterinary medicine.

10.12. NORMAL ULTRASONOGRAPHIC APPEARANCE OF THE STOMACH

The gastric wall has a characteristic layered appearance when imaged with a high-resolution system. The ultrasonographic layers are generally considered to correspond to histological regions (Fig. 10.9).

The gastric wall is arranged to form rugal folds but should otherwise be smooth and of uniform thickness. If the stomach is empty and contracted, the wall will appear thicker than if the stomach is distended. Peristaltic and segmental contractions are normally seen, at a rate of 4–5 contractions per minute in the normal dog. Normal wall thickness is given in Table 10.1.

| aDelaney, F., O’Brien, R.T. and Waller, K. (2003) Ultrasound evaluation of small bowel thickness compared to weight in normal dogs. Veterinary Radiology and Ultrasound44, 577–580. | ||

| bPuppy values will be at the lower limits. | ||

| cMay be thicker in sedated cats. | ||

| Region and Weight of Animal | Wall Thickness (MM) | |

|---|---|---|

| Dogb | Cat | |

| Stomach: inter-rugal | 3–5 | 3–5 |

| Duodenuma | 3–6 | 2–3c |

| < 20kg | < 5.1 | |

| 20–30kg | < 5.3 | |

| > 30kg | < 6 | |

| Jejunuma | 2–5 | 2–2.5 |

| < 20kg | < 4.1 | |

| 20–30kg | < 4.4 | |

| > 30kg | < 4.7 | |

| Colon | 2–3 | 1.5–2 |

10.13. VARIATIONS IN GASTRIC CONTENTS ON ULTRASONOGRAPHY

1. Anechoic with hyperechoic specks – indicates fluid content with air bubbles, debris or mucus.

a. Normal – recent ingestion of fluid.

b. Retained fluid secondary to gastric outflow obstruction or proximal small intestinal obstruction (peristalsis may be increased or diminished).

c. Retained fluid secondary to functional ileus (peristalsis diminished or absent).

– After abdominal surgery.

– Peritonitis or pancreatitis.

– Electrolyte disturbances.

– Renal failure.

d. Gastrointestinal perforation.

e. Gastric ulcers.

2. Solid material of variable echogenicity outlined by fluid.

a. Food remnants.

b. Foreign material.

c. Pedunculated gastric mass.

3. Heterogeneous material filling the stomach, with or without acoustic shadowing.

a. Recent ingestion of food.

b. Retained food secondary to gastric outflow obstruction.

c. Foreign material.

d. Blood clot.

10.14. LACK OF VISUALIZATION OF THE NORMAL GASTRIC WALL LAYERED ARCHITECTURE ON ULTRASONOGRAPHY

10.15. FOCAL THICKENING OF THE GASTRIC WALL ON ULTRASONOGRAPHY

1. Retention of the normal layered architecture.

a. Normal rugal folds.

b. Localized hyperplastic gastropathy.

c. Pyloric hypertrophy – circumferential thickening of the pylorus (in the dog, wall thickness ≥ 9mm, with the muscular layer ≥ 4mm).

d. Neoplasia.

– Leiomyoma.

– Malignant histiocytosis.

e. Polyp – may be sessile or pedunculated; usually echogenic and confined to mucosa.

f. Increased number of layers – pylorogastric intussusception.

2. Loss of the normal layered architecture.

a. Neoplasia.

– Adenocarcinoma (typically asymmetrical, heteroechoic thickening).

– Leiomyoma or leiomyosarcoma.

– Lymphoma (typically symmetrical, hypoechoic thickening) – especially cats.

– Malignant histiocytosis.

b. Gastric ulcer – may contain hyperechoic gas speckles.

c. Necrotizing gastritis – may contain hyperechoic gas speckles.

d. Pyogranulomatous disease, especially Pythium insidiosum*.

10.16. DIFFUSE THICKENING OF THE GASTRIC WALL ON ULTRASONOGRAPHY

1. Retention of the normal layered architecture.

a. Contracted, empty stomach.

b. Severe gastritis.

c. Chronic hyperplastic gastropathy.

d. Wall oedema.

– Right heart failure.

– Hypoproteinaemia.

– Acute gastritis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree