Chapter 102 Fractures of the Shoulder

Recognition of shoulder fractures is important to allow acute lameness diagnosis and treatment and to protect normal shoulder joint mobility and function. Fractures of the shoulder are often associated with concurrent thoracic trauma and may be associated with ipsilateral brachial plexus injuries or trauma to the overlying soft tissues.

ANATOMY

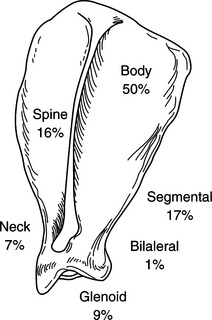

The scapula is a broad, flat bone with a prominent spine and numerous muscle origins and insertions. It is loosely attached to the chest wall through the insertions of a number of muscles, including the rhomboideus, subscapularis, and trapezius. Scapular areas can be anatomically divided into the body, spine, neck, and glenoid cavity, with differing surgical approaches and treatments recommended for fractures in each area (Fig. 102-1). In immature animals, the dorsal border of the scapula serves as a physis for long bone growth. The distal scapula has no physis for long bone growth, but the supraglenoid tubercle is a secondary center of ossification in the immature dog and this apophysis is often misdiagnosed as a fracture in dogs until radiographic closure from 6 to 7 months of age.

DIAGNOSIS

Radiography

Definitive diagnosis of scapular fractures is by radiography. Reported radiographic views of the scapula include caudocranial, mediolateral, dorsally displaced mediolateral, and distoproximal. Any or all of these views may be useful for the surgeon’s understanding of the fracture’s configuration. Frequently, computed tomography (CT scan) of the scapula is useful to determine the degree of comminution and provide operative planning, particularly with the addition of three-dimensional reconstructions of the fracture available in some software. In a study of 107 dogs with scapular fractures, 28% were comminuted fractures, but only one fracture was an open fracture. Nuclear scintigraphy of the scapula may be useful to identify non-displaced scapular fractures. In young animals, diagnosis of supraglenoid tubercle fracture should not be made until comparison with radiographs of the opposite scapula indicates an obvious displacement of the affected supraglenoid tubercle.