Chapter 5 Fluid Therapy for Dogs and Cats

Fluid therapy can be the single most important therapeutic measure used in seriously ill animals. Effective administration of fluids requires an understanding of fluid and electrolyte dynamics in both healthy and sick animals. An overview of a general approach to fluid therapy decision making can be found in Figure 5-1.

Figure 5-1 General decision tree for fluid therapy.

(From Finco DR: A scheme for fluid therapy in the dog and cat. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 8:178–180, 1972.)

DECISION-MAKING CHECKLIST

Answer these questions to decide when fluid therapy is needed:

Answer these questions in order to provide appropriate fluid therapy:

INDICATIONS FOR FLUID THERAPY

DISTRIBUTION OF BODY WATER AND ELECTROLYTES

Water

MAINTENANCE REQUIREMENTS

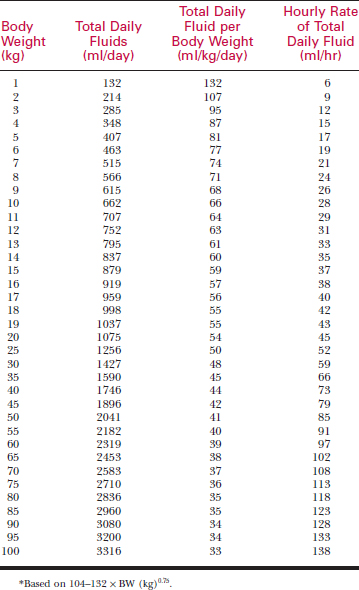

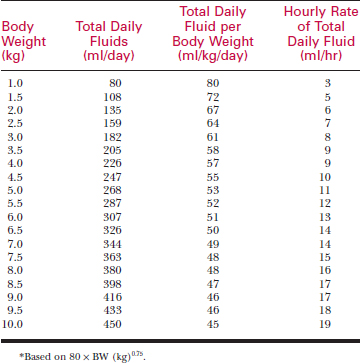

Maintenance is defined as the volume of fluid (ml) and the amount of electrolyte (mEq or mg) that must be taken in on a daily basis to keep the volume of TBW and the electrolyte content normal. Obligatory losses of water and electrolytes occur daily as a consequence of normal metabolism. Water taken into the body in all of its forms is equal to the loss of water in the normal animal. See Figure 5-2 for specific maintenance requirements of electrolytes and water in caged dogs and cats that have normal food intake.

Figure 5-2 Maintenance fluid and electrolyte requirements for caged normal dogs and cats.

(Finco after Harrison JB: J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 8:179, 1972.)

DEHYDRATION (REPLACEMENT NEEDS)

Dehydration exists when TBW decreases to less than normal.

Causes of Dehydration

Decreased Water Intake (Hypodipsia, Adipsia)

Characterization of Dehydration (Type)

Detection of Dehydration

Clinical tools to detect dehydration are limited in both sensitivity and specificity. There is no single test or procedure to accurately assess the magnitude of dehydration. Integration of historical findings, abnormalities on physical examination, and laboratory measurements will be necessary to quantify dehydration. Dehydration is not detectable by clinical means until approximately 5% of body weight in water has been lost. An acute loss of greater than 12% body weight in water is considered life threatening (Table 5-3).

Table 5-3 PERCENTAGES OF DETECTABLE DEHYDRATION

| Dehydration | Signs |

|---|---|

| <5% | Not detectable on physical exam; history is suggestive of losses; acute body weight changes |

| 5% | Subtle loss of skin elasticity |

| 6–8% | Mild delay of skin tent, slight prolongation of CRT, dry mucous membranes |

| 8–10% | Obvious delay of skin tent, slight prolongation of CRT, dry mucous membranes, eyes slightly sunken in orbits |

| 10–12% | Severe prolongation of skin tent, eyes sunken in orbits, dry mucous membranes, signs of shock likely present (prolonged CRT, tachycardia, weak pulses etc.) |

| >12% | Moribund |

*CRT, capillary refill time.

History

History often leads the clinician to suspect dehydration and to assess its magnitude more accurately. Question the owner about volume of intake (adipsia, hypodipsia, polydipsia, or normal intake of water). Because volume of water intake may, in part, be a function stimulated by food intake, note also the presence or absence of anorexia. Abnormal losses of body fluid may be determined from owner responses to questions about vomiting, diarrhea, polyuria, panting, excessive salivation, or other bodily discharge. The duration of these historical signs and the magnitude of losses affect the magnitude of clinically detectable dehydration.

Physical Examination

Physical examination provides general guidelines for detecting dehydration but is subjective (see Table 5-3). Signs of listlessness and depression may occur from dehydration but may be partially attributable to the underlying disease or to concomitant electrolyte and acid-base abnormalities. As dehydration becomes more severe, decreased skin turgor, sunken eyes, dryness of mucous membranes, tachycardia, diminished capillary refill, and signs of shock may occur. An accurate and recent body weight, when available, can be used for comparison to evaluate change in body weight as an indicator of body water change.

Skin Turgor

Skin turgor assessment during physical examination is important for estimating the percentage of body weight loss due to dehydration. Skin turgor is evaluated by determining the time required for skin gently lifted from the body to return to its original position (referred to as the skin pinch or skin tent). Normal skin pliability (skin turgor) depends on hydration of the tissues in the area tested. Skin turgor is largely determined by hydration status of the interstitial tissues, although both vascular and intracellular hydration also contribute. Elastin and adipose within skin and subcutaneous tissues will also influence the apparent skin turgor. Choose skin from the trunk as a test area. Avoid dependent areas and skin from the neck. Normal skin returns immediately to its initial position when lifted a short distance and released. Dehydrated skin shows varying degrees of slow return to the original position. As dehydration progresses, the time required for the return of the skin pinch to its initial position becomes greater. The clinician assigns increasing percentages of dehydration to abnormal skin turgor of increasing severity (see Table 5-3).

Skin Turgor Artifacts

Many artifacts confuse interpretation of skin turgor.

Laboratory Assessment of Dehydration

Packed Cell Volume and Total Plasma Protein

Simple laboratory testing is helpful in evaluation of intravascular hydration. Packed cell volume (PCV) recorded in percentages (SI unit: L/L) and total plasma protein (TPP) recorded in gm/dl (SI unit: g/L) can be rapidly and inexpensively determined using microhematocrit tubes and a refractometer. These two tests require only a few drops of blood and can be taken by capillary action from a 25-gauge venipuncture. TPP concentration may be more helpful in the detection of dehydration than PCV. Increased TPP and PCV provide documentation for intravascular dehydration. Simultaneous evaluation of PCV and TPP is recommended in order to minimize interpretation errors due to pre-existing anemia or hypoproteinemia. (Table 5-4) Additional value is obtained when PCV and TPP are followed serially as increasing values identify progressive dehydration.

Table 5-4 INTERPRETATION OF CHANGES IN PACKED CELL VOLUME (PCV) AND TOTAL PLASMA PROTEIN (TP)

| PCV | Total Protein | Possible Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| ↑ | ↑ | Dehydration |

| ↑ | N or ↓ | Splenic contraction |

| Erythrocytosis | ||

| Hypoproteinemia with dehydration | ||

| N | ↑ | Hyperproteinemia |

| Anemia with dehydration | ||

| Hypertonic dehydration (RBC shrinkage) | ||

| ↓ | ↑ | Anemia with dehydration |

| Anemia with pre-existing hyperproteinemia | ||

| ↓ | N | Non-blood-loss anemia, normal hydration |

| N | N | Normal hydration |

| Dehydration, after secondary compartment shift | ||

| Dehydration with pre-existing anemia + hypoproteinemia | ||

| Acute hemorrhage | ||

| ↓ | ↓ | Blood loss anemia |

| Overhydration |

Serum Biochemistry

Evaluation of serum electrolytes may help characterize the nature of the fluid that was lost.

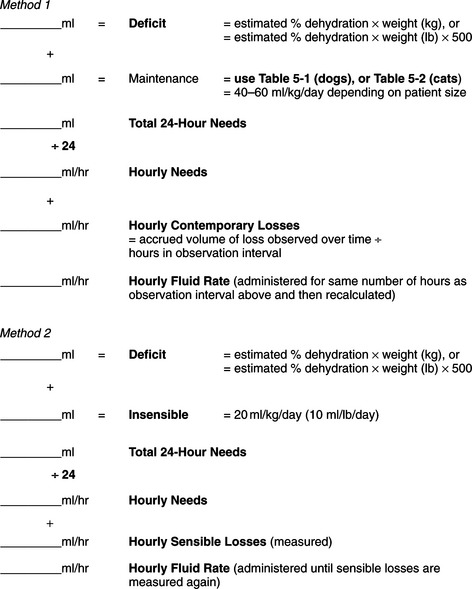

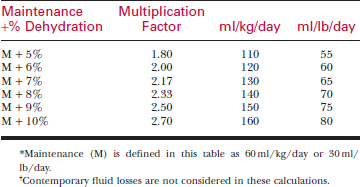

Correction (Replacement) of Dehydration

Contemporary (Ongoing) Losses

Although initiation of fluid therapy is aimed at replacing fluid lost from the patient, persistence of uncontrolled signs or untreated diseases will permit the dehydrating process to continue. Consider replacement of contemporary or ongoing losses that begin after fluid therapy has begun. Estimate gastrointestinal fluid loss (e.g., from vomiting or diarrhea). When ongoing loss is from the urinary tract, temporary urethral catheter collection may increase the accuracy of estimating the magnitude of the loss. Less invasive but feasible methods of estimation include collecting urine in a container (free catch from dogs or litter box from cats) and measuring the volume or weight change of the container.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree