CHAPTER 6 Field Anesthesia

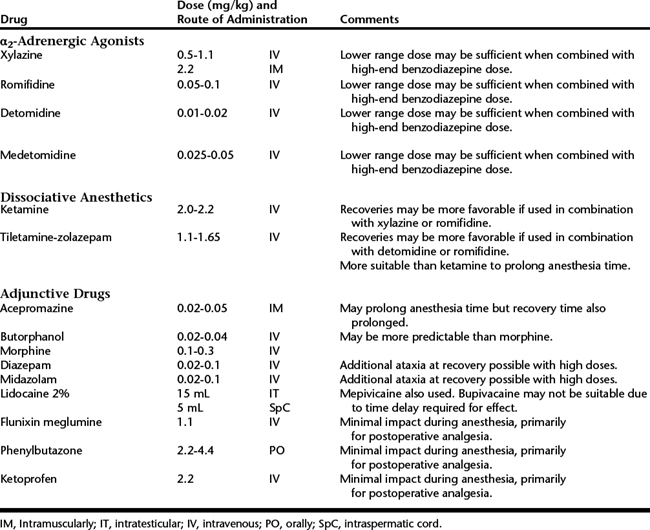

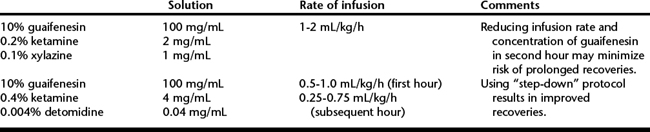

Field anesthesia, generally performed using intravenous (IV) anesthetic techniques, is a familiar procedure for most equine veterinarians. The use of inhalant techniques, although not impossible in the field, is usually limited to the hospital setting because of the inherent complexity of inhalant anesthesia and the high cost and lack of readily portable anesthetic equipment. However, the fact that IV anesthetic techniques appear to be less complex does not mean that less attention should be given to the anesthetic portion of the procedure. Proper preparation is essential to ensure predictability and success of field anesthesia. Preparation should include ensuring that the surgical procedure is appropriate for field conditions, selection of a suitable procedure location, preparation of the horse, ensuring availability of appropriate personnel and adequate equipment for support and monitoring of the horse, and selection of anesthetic drugs and technique (Tables 6-1 and 6-2).

A means of providing airway, breathing, and circulatory support should be available for all horses undergoing general anesthesia. A cuffed large-animal endotracheal tube (20- to 26-mm inner diameter); E-sized oxygen tank; demand valve; paramedic combination regulator/flowmeter with two ports, a barbed oxygen port for insufflation and a high-pressure port for connection to demand valve; and IV fluids constitute a reasonable anesthetic support kit (Box 6-1). All these components can be conveniently stored and carried in a standard paramedic transport bag (Figure 6-1).

Box 1 Sources of Equipment for Large Animal Anesthesia

Anesthesia Machines, Ventilators, Monitors, Demand Valves, Supplies

Monitoring the horse should not be neglected during the anesthetic period. The quality of reflexes, respiratory rate, and response to surgery are commonly evaluated to assess the depth of anesthesia. Horses anesthetized with IV anesthetic protocols generally maintain more brisk facial reflexes than those anesthetized with inhalant techniques. Cardiopulmonary function is monitored by observation of chest excursions, palpation of the pulse, and auscultation of the heart. Several portable monitors are available that can be used to more critically and objectively evaluate cardiopulmonary performance. A Doppler probe and cuff can be used over the coccygeal artery to assess blood pressure in addition to heart rate and rhythm. One desirable feature of the Doppler unit is that it produces an audible signal that enables the surgeon to monitor heart rate and rhythm continually throughout the procedure. Several portable pulse oximeters are also available that can be used to evaluate hemoglobin saturation and provide an assessment of ventilation and oxygenation.