Chapter 8

Feeding and the Problem of Obesity

- 8.1 Introduction

- 8.2 How Is ‘Fatness’ Defined and Measured in Cats and Dogs, and How Many Animals Are Affected?

- 8.3 Is This a Welfare Problem?

- 8.4 Why Do Owners Allow Their Companion Animals to Become Fat?

- 8.5 Whether and How to Prevent and Treat Problems with Overweight Companion Animals

8.1 Introduction

One of the most basic concerns of animal care is to ensure that animals are properly fed. This is reflected in the first principle of the ‘Five Freedoms’ (see Chapter 4, p. 67), set up to define the basic requirements of animal welfare by the British Farm Animal Welfare Council (now Farm Animal Welfare Committee). The principle states that animals must enjoy ‘Freedom from hunger and thirst – by ready access to fresh water and a diet to maintain full health and vigour’ (FAWC, 2009).

Historically, underfeeding and malnutrition were major issues, although this is no longer the case for dog and cat populations in richer parts of the world. Occasionally, however – even in rich countries – individuals still keep large numbers of dogs and cats without being able to feed them a proper diet, while stray and feral cats and dogs may also suffer from thirst, starvation and malnutrition (see Chapter 13).

In general, however, companion animals are increasingly viewed as family members, clearly benefiting from the affluence of their owners. Parallel to – and partly caused by – this development, there has been a significant change in the way people feed their companion animals. Rather than feeding them scraps and leftovers, increasing numbers of dogs and cats are fed readymade feed, either in a dry or a wet (canned) form. The production of this feed is regulated to ensure a proper composition of macronutrients and a sufficient amount of vitamins, minerals and other micronutrients (Nestle & Nesheim, 2010).

Slaughter by-products not considered fit for human consumption make up a significant part of the ingredients for commercial pet food, and it may be argued that this serves to limit the environmental footprint of the growing companion animal pet food sector (Nestle & Nesheim, 2010, see also Chapter 14). Nonetheless, questions may still be raised about killing some animals to feed others, how sustainably the meat and fish in pet food have been produced, and food contamination. We will consider these questions further in Chapters 14 and 16; the rest of this chapter will focus on the consequences for companion animals of the amount of food they are eating.

Whatever the quality of the diet fed to companion animals, it can still be fed in too large quantities. Overfeeding, particularly in combination with too little exercise, leads to obesity and increases the risk of related diseases, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, skeletal disease and various forms of cancer. These diseases shorten the expected lifespan of the animals, and often adversely affect their quality of life. There are also negative impacts on the owners in terms of worry and grief about their companions’ health and early death, as well as the potential costs of veterinary treatment.

In this chapter, we focus on the problem of overfeeding dogs and cats, and how the problem is brought about via the animals’ companionship with humans. Human lifestyles influence and affect companion dogs and cats to a significant degree, and it is not surprising that the current epidemic of human obesity in many parts of the world is increasingly mirrored in companion animals.

We begin by considering how ‘fatness’ is defined in dogs and cats, and then look at how their health and welfare is affected when they exceed their ideal weight. This opens up an ethical dilemma about whether maximising longevity and minimising morbidity, or avoiding the feeling of hunger, is better for animal welfare. We then review what is known about why owners of dogs and cats allow their companions to become overweight, and about the barriers that prevent dogs and cats remaining close to their ideal weight. We conclude with a discussion of various means of overcoming these barriers.

8.2 How Is ‘Fatness’ Defined and Measured in Cats and Dogs, and How Many Animals Are Affected?

In companion animals, as in human beings, a distinction is drawn between being overweight, and being obese. Being overweight can be defined as having a body condition where levels of body fat exceed what is considered optimal. Obesity can be defined as being overweight to the extent that serious effects on the individual’s health become likely.

Various values are given in the literature for optimal % body fat, ranging from 15–20% for cats and dogs (Toll et al., 2010: p. 501) to 20–30% body fat for cats (Bjørnvad et al., 2011). According to one expert, the value for optimal % body fat depends on a number of factors including the measurement technique, and age, breed and gender of the animal. He proposes the optimal % of body fat to be between 10–20% in cats, and 10–35% in dogs, depending on breed and circumstances (Alex German, personal communication).

It is possible to use relative body weight as a proxy measure of % body fat. A recent review paper defines overweight cats and dogs as being 10–20% above optimal weight, and obese animals as being more than 20% over optimal weight (Toll et al., 2010: p. 501). In another review paper, obesity is defined as occurring at 30% above ideal body weight (Burkholder & Toll, 2000). However, ‘these criteria have not been confirmed with rigorous epidemiologic studies, and limited data exist on the nature of an optimal body weight’ (German, 2006: p. 1940).

Although most people would claim to recognise a ‘fat’ dog or cat when they see one, it is more difficult to distinguish between a normal versus an overweight animal and an overweight versus an obese animal. Thus, as well as agreeing on definitions of ‘overweight’ and ‘obese’, it is also necessary to develop a reasonably accurate, practical method of assessment. In the case of humans, the body mass index (BMI) has been developed: by using the BMI, an individual’s body fat can be estimated based on information about the person’s weight and height, and it is used to determine whether the individual is of a healthy size or not. Such a simple (albeit somewhat problematic and controversial) measure is not easily transferable particularly to dogs, as there are many diverse breeds with very different body conformations.

However, practical measures have been developed which, in a fairly easy and reliable way, enable people to score the amount of body fat of many animals, including dogs and cats. These so-called body condition scores use a number of categories, ranging from ‘emaciated’ to ‘severely obese’, based on subjective assessment of specific features. These features include the shape of the animal viewed from above, and how easily palpable the ribs are (Laflamme, 1997; McGreevy et al., 2005; Toll et al., 2010). Studies have shown that such measures correlate well with more advanced measurements of the amount of body fat, and, in general, there is good agreement between measurements across different users (German et al., 2006) (Figure 8.1).

Figure 8.1 Body Condition Score chart. Many such charts are available to help owners of cats and dogs recognize whether their companion animal is in a healthy body condition.

(Image used courtesy of World Small Animal Veterinary Association Global Nutrition Committee.)

However, a recent Danish study (Bjørnvad et al., 2011) of indoor-confined, adult neutered cats found that the body condition score tends to underestimate the level of body fat as measured using a DEXA (Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry) scanner. Due to lack of exercise, these cats are in a condition that, in the human case, has been labelled ‘skinny fat’. As with some physically inactive people, due to a decrease in lean body mass, these cats have a relatively high level of body fat despite what appears to be a healthy body weight; as in the human case, ‘skinny fat’ can lead to type 2 diabetes and other serious health problems.

A number of studies have been undertaken in North America, Europe and Australia, mainly on dogs, to determine what proportions of animals are overweight or obese: the reported prevalence was between 22% and 44% (Crane, 1991; Edney & Smith, 1986; Hand, Armstrong & Allen, 1989; Kronfeld, Donoghue & Glickman, 1991; Mason, 1970; Mcgreevy et al., 2005; Robertson, 2003). Two studies (Lund et al., 2005, 2006) used a cross-sectional design to measure the prevalence of overweight and obese animals among a large number of cats (n = 8159) and dogs (n = 21,754) seen by US veterinarians. They found that 28.7% of adult cats were overweight and a further 6.4% were obese; for adult dogs, the numbers were 29.0% and 5.1%.

The differences in the prevalence of overweight and obese animals reported in the literature may reflect differences in sampling, in who has been asked (owners or vets), or genuine local variations. Local variations are found in the levels of human obesity: in adults in the United States, it is over 30%, compared to between 8 and 25% in European countries, and less than 5% in some Asian countries, such as Japan (WHO, 2012). Nonetheless, as a rough estimate, around a third of adult cats and dogs kept as companions in the rich parts of the world are overweight, and more than 1 in 20 is obese. Experts in the field believe that the problem is increasing (German, 2006).

8.3 Is This a Welfare Problem?

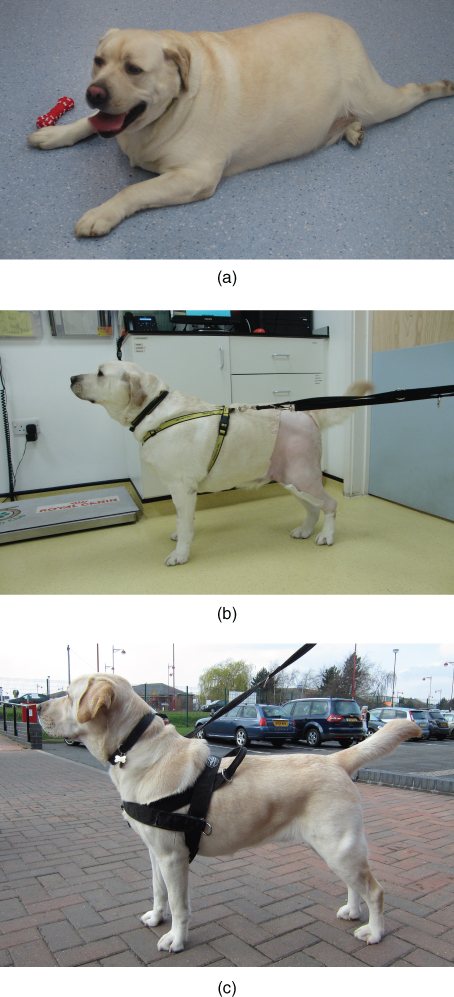

There is a huge body of veterinary literature documenting that obesity in dogs and cats increases the risk of other health problems. According to one review paper, these problems include ‘orthopaedic disease, diabetes mellitus, abnormalities in circulating lipid profiles, cardio-respiratory disease, urinary disorders, reproductive disorders, neoplasia (mammary tumours, transitional cell carcinoma), dermatological diseases, and anaesthetic complications’ (German, 2006: p. 1940S). As these conditions shorten the expected lifespan of the affected animals, and potentially reduce their quality of life, obesity in cats and dogs has considerable potential to cause reduced welfare (Figure 8.2(a)–(c)).

Figure 8.2 ‘Mighty Mike’, a rescue dog. (a) Initially weighing 60 kg, Mike suffered from a ruptured cranial cruciate ligament in the left hind leg. (b) Shortly after having surgery to stabilise his left knee, weighing 50 kg. (c) Mike required surgery for the same condition in his other knee several months later. He is shown here, fully recovered, weighing 36.6 kg.

(Courtesy of Sandra Corr.)

Even being moderately overweight seems to have a negative effect on animal health, for example, rodents fed ad libitum have a shorter lifespan than those on a restricted diet (Hubert et al., 2000). In a series of papers, Kealy et al. (2002) and Lawler et al. (2005, 2008) reported the results of a longitudinal study of two randomly selected groups of Labrador Retriever dogs, with 24 dogs in each group, treated identically apart from their feeding regime. One group was initially fed ad libitum, then fed at a level at which they stayed overweight but did not become obese (mean body condition score around 6.5 on a scale ranging from 1 – emaciated, to 9 – severely obese). The other group was fed 25% less than the first group throughout the study. Dogs in the latter group remained leaner and lived longer (median lifespan of 13.0 years compared to 11.2 years for the moderately overweight group). In addition, where the dogs in the leaner group developed the same diseases as those in the overweight group, the onset of disease came later and the symptoms of the diseases were less severe.

Thus, overweight companion animals potentially lose many years of life, despite the fact that the lifespan of dogs and cats seems to have been increasing overall (Kulick, 2009), most likely due to improvements in the quality of nutrition and better veterinary care.

On the other hand, work with rodents and pigs also indicates that a restrictive diet of the sort that secures maximum longevity and minimum morbidity causes welfare problems in the form of increased hunger, derived effects in terms of increased aggression and elevated levels of stress and the development of stereotypies (D’Eath et al., 2009; Kasanen et al., 2010). Assuming that the same conclusions apply to dogs and cats, there may be a real dilemma here between two of the five freedoms mentioned in Chapter 4: it may not always be possible to secure both freedom from hunger and from disease.

D’Eath et al. (2009) have argued that this is a significant dilemma in respect to keeping laboratory, companion and some farm animals. Kasanen et al. (2010: p. 40) state that: ‘One could argue that the best solution is simply to proceed with feeding ad libitum, allowing the rats to be fat and friendly rather than lean and mean. A similar line of thought seems to apply to fattening pigs’. This solution may be appropriate for farm and laboratory animals, which are killed at a relatively young age, before they develop conditions such as osteoarthritis or heart disease later in life. However, this does not apply to cats and dogs that (barring accidents or other unexpected occurrences) normally live until they are euthanased due to a specific disease or from deteriorating health in old age.

Of course, there may be ways to make the dilemma between preventing hunger and protecting health less stark. Animals may be able to eat more without detrimental effects to their health if they also exercise more, or are fed low-calorie bulk diets that nonetheless provide a feeling of satiety. They could also be made to work for their food, thereby engaging in more feeding-related behaviours without getting too much food. However, these methods are not likely to completely solve the issue of which feeding strategy provides optimal welfare.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree