Chapter 49 Feeding and Nutrition of Anteaters

Anteaters

A few studies have been published on the dietary habits of anteaters that show the type and composition of prey selected by these animals in the wild. The natural diet of giant anteaters (Mymecophaga tridactyla) is composed 96% of ants and 4% of termites (Camponotus and Solenopsis spp.).16,23 In Brazil, this species of anteater may consume approximately nine different ant species, but in June they switch to consume termites.11 Some anteaters, such as the tamandua, are highly specialized predators, consuming mainly ants and termites, but preferring the reproductive and worker castes.10,17 Occasionally, anteaters will consume other invertebrates but avoid prey with large jaws, strong chemical defenses, or spiny bodies. Anteater tongues may reach out 60 cm with an amazing mobility (150 times/min) and may consume up to 30,000 ants/day.27 Silky anteaters (Cyclopes didactylus), a nocturnal animal that lives mainly in the trees, will consume termites and beetles, but their main diet is ants. Medical issues (e.g., hair loss, conjunctivitis) has been observed when feeding silky anteaters captive diets in Peru consisting of a mixture of dog milk replacer, sunflower oil, barley, and yeast, with vitamin and mineral supplements.26 Studies on the nutrient content of several species of termites have found that fat, ash, and nitrogen levels vary based on termite castes. Species that tended to be high in ash were low in fat and nitrogen. In the case of Grigiotermes metoecus, they are high in ash because of geophagy, with soldiers low in fat, but reproductive and alate forms were high in fat. Alate nymphs of Procornitermes araujoi had 24% fat; soldiers and workers of Armitermes had 42% ash and 3.64% nitrogen. In their natural environment, tamanduas feed almost exclusively (95% by volume) on termites (Nasutitermes spp.) and ants (Crematogaster and Camponotus spp.), with the rest of the diet consisting of stingless bees, heteropterans, unidentified insect pupae, and seeds.2

Nutritional Considerations

Nutritional Disorders

There have been a number of varied disorders seen in anteater species relating to nutrition. Rear limb paresis progressing to complete flaccid paralysis and extensive hyperostosis of the thoracic, lumbar, and coccygeal vertebrae has been reported in T. mexicalis.3 The symptoms probably were related to vitamin A toxicosis or excess vitamin D and/or calcium.21 Similar lesions have been reported in tamanduas in European zoos that had been consuming a diet with high levels of vitamin A (>20,000 IU/kg dry matter [DM]).5 However, in one study of the natural diet of T. tetradactyla, the authors reported that the mean vitamin A value of Nasutitermes spp. was 24,773 IU/kg. Most of the invertebrates used in zoo diets will have much lower vitamin A levels, ranging from approximately 60 IU/kg (snails) to 2400 IU/kg (earthworms, crickets).5,25 Requirements of vitamin A in domestic animals such as dogs and cats range from 5000 to 10,000 IU/kg DM.20

Other nutritional problems, including vitamin K deficiency, liquid feces probably caused by high levels of grain and lactose products in the diets, and constipation caused by lack of fiber and tongue problems, have been observed in anteaters kept in North American and European zoos.18,19 Similar to domestic cats, low blood and plasma taurine concentrations have been associated with dilated cardiomyopathy in giant anteaters and used as early diagnostic indicators.1,28 Taurine whole blood levels below 300 nmol/mL, (normal range = 300 to 600 nmol/mL) and plasma levels below 60 nmol/mL (normal range = 60 to 120 nmol/mL) might be associated with the presence of cardiomyopathies in giant anteaters. The use of dog chow as a food item has been given as the reason for the taurine-deficient dilated cardiomyopathy in giant anteaters.1 Dogs, unlike cats, do not require taurine in their diet, provided there are sufficient sulfur amino acids for taurine synthesis. Similarly, symptoms of taurine deficiency have been reported in young tamandua when fed cat and dog milk replacers.15 Vitamin K deficiencies in anteaters had been reported in the past. This suggested that ant and termite eaters have the tendency to have hemorrhagic problems unless supplemented, particularly when the animals had been treated with antibiotics.12 In the last decade, diabetes has been reported in T. tetradactyla in zoological institutions.24 In one case, the animal had been fed a mixture of primate and feline dry chows (see later). At the Cleveland Zoo, two tamanduas have been diagnosed with diabetes. Retrospective studies on the health and nutrition of tamandua in Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) institutions are presently being conducted at Ohio State University–Cleveland Metro Parks Zoo.4

Anteater Diets in Zoos

It is difficult to mimic the natural anteater diet in zoos by providing specific ants and termites to consume, as in the free-ranging state, so alternative food choices available in the market are used to develop their diets. The selection of these foods becomes a challenge if we want to provide good nutrition and be able to satisfy behavioral needs. However, little is known of the exact nutritional needs and nutrient requirements of insectivorous mammals, presenting another significant challenge for captive-kept animals. Because anteaters are specialized carnivores, the nutrient requirements established for domestic cats and dogs may be used as models when developing and evaluating the nutritional value of their diets in captivity. These data might be able to provide a range of nutrient values that can be used as general guidelines. Historically, in zoological institutions, anteaters are fed diets that consist of mixtures of different ingredients; these may include milk products, eggs, ground raw meat (horse or beef), dog chow, canned dog food, yogurt, commercial carnivore diets, multivitamins, trace mineral supplements, human protein supplements, and fruits (e.g., ripe bananas, oranges, limes, avocados, mangos). Normally, the ingredients were offered as a gruel mix, with additional vitamin K possibly added. Diets that include these ingredients have been previously described and were extensively used when zoos first added anteaters to their animal collections.7-9,12-14 These diets, developed at Lincoln Park Zoo, led to some success in maintaining and reproducing anteaters. However, until the early 1990s, North American and South American zoos had a poor record of keeping and reproducing tamanduas.3 Poor survival during the early years was probably related to their specialized dietary requirements. Several problems with the first diets used in zoos led to the development of new diets in the early 1990s.

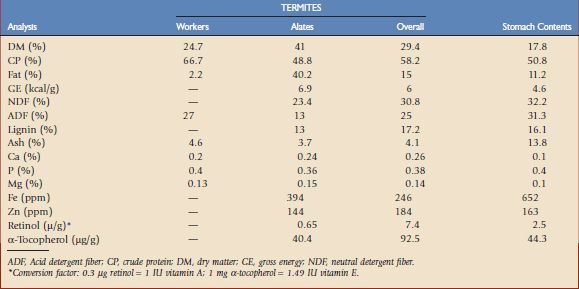

One of the diets, developed in the early 1990s was based on a study of the nutrient composition of the natural diet of tamandua in the Llanos of Venezuela.21 The goal of this study was to obtain baseline information through the collection and analysis of termites, one of the tamanduas’ main prey items, as well as tamandua stomach contents. The summary of the results is given in Table 49-1. We found that the consumed diet of free-ranging tamandua contained 50.9% crude protein, 11.2% fat, 13.9% ash, 31.3% acid detergent fiber, 0.11% calcium, 0.41% phosphorus, 2.52 µg/g retinol, 44.35 µg/g α-tocopherol, and 4.58 kcal/g of gross energy on a dry matter basis. This information was used to help with the formulation of tamandua and anteater zoo diets in North American institutions and elsewhere. For example, after adjusting nutrient levels (e.g., calcium), the Toronto Zoo was able to replace or modify the traditional Lincoln Park Zoo diets (Table 49-2). This or similar diets are also used in other North American and Central and South American zoos.22 With the development of commercial insectivore pellets (see Table 49-2), feeding anteaters has become easier, although not perfect. The gruel-type diets such as the one developed in Toronto, are better than previous anteater gruel diets because the nutrient profile is generally closer to the one found in the natural diet, avoiding excesses, like the ones previously reported.3 However, this diet still lacks sufficient amount of daily fiber (acid detergent fiber [ADF]) if compared with the natural diet (see Table 49-1). The addition of artificial fiber (e.g., Solka-Floc, International Fiber, Tonawanda, NY) or commercial insectivore pellets to the gruel diets may improve their fiber content (see Table 49-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree