Chapter 10 Feeding and diet-related problems

The physiological influence of diet on behavior

The innate feeding instincts of dogs and cats include both hunting (comprised of prey seeking, stalking, chasing, and the kill) and scavenging. These activities utilize energy and are a significant component of an animal’s daily time budget. Studies have found that cats living exclusively outdoors might capture 10–20 small prey per day to satisfy their caloric requirements and that less than half of the capture events are successful.1,2 Similarly domestic cats eat many small meals over 24 hours. The dog on the other hand might spend a large proportion of its day exploring, scavenging, hunting, and catching. In addition, humans have selected for pointers, retrievers, terriers, and setters that can find, track, contain, retrieve, or hunt down prey. Therefore, behavior problems are likely to arise if sufficient attention is not made to the feeding and hunting requirements that are natural for the species (and breed). Behavioral assessment should include an evaluation of whether the pet has sufficient outlets to display its natural repertoire of behaviors, including the time and activities that would normally be spent in food acquisition. Treatment might then require more stimulating, time-consuming, and natural ways for pets to feed. Although feeding live prey or dead carcasses is impractical, providing toys and feeders that require manipulation to release the food, utilizing search games where the pet has to find its food, training the pet to receive pieces of its food as a reinforcement for desirable behavior (i.e., training), or stuffing food in toys and freezing can increase the work required to obtain food rewards (see environmental enrichment in Chapter 4).

Dietary ingredients and behavior

Protein, carbohydrate, and tryptophan

Most concerns regarding diet and behavior focus on the role of protein, including quantity, quality, and processing. High-meat diets could conceivably result in lowered levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin in the brain, because of the high level of amino acids competing with tryptophan (from which serotonin is formed) for the carrier that transports amino acids across the blood–brain barrier. Low serotonin levels have been associated with aggression in some animals.3 Therefore, could a reduction in protein with concurrent supplementation with tryptophan lead to a reduction in aggression? Another suggestion is that a reduction in carbohydrate content and increased protein may lead to a decrease in excitability and overactivity. Studies that measure serotonin metabolites in the cerebrospinal fluid after ingestion of diets with a variety of protein levels in dogs have found no differences regardless of diet fed.4 In addition, the level of protein (high versus low) in the diet or addition of l-tryptophan appears to have no effect on fearfulness or hyperactivity.5 Yet, in a small population of dogs, low-protein diets were found to reduce territorial aggression.6 Other forms of aggression were unaffected. In a preliminary placebo-controlled study, supplementation with l-tryptophan led to a reduction of stress-related behaviors and a decrease in anxiety signals in both dogs and cats.7 Recently, a new diet Royal Canin CALM™ Canine and Feline with l-tryptophan, vitamin B6, alpha-casozepine (see chapter 9) and l-tryptophan (in an increased ratio to other large amino acids) has, in one study, demonstrated a reduced stress response (as measured by urine cortisol creatinine ratio) in response to nail trimming.8

Carbohydrate levels are another area of interest. It is believed that when high-carbohydrate diets are fed, tryptophan reaches the brain in higher amounts and results in the production of serotonin. This may have a calming effect on the animal, making it less aggressive. However, if the increase in carbohydrates is accomplished by decreasing protein in the diet, then this may be a contributing factor. Supplementing the diet with vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) might also be beneficial, because this aids in the production of serotonin.8

Another concern, often posed by dog trainers, is that training problems are more common in dogs fed dry food than those fed a canned ration. If training problems related to dry rations exist, they would more likely be related to ingredients such as preservatives than low moisture content. Since canned food is heat-sterilized before packaging, preservatives are not needed. In dry foods expected to last for months on store shelves, many chemicals, especially antioxidants and flavor enhancers, must be added. Only recently has any scientific research focused on the effects of various components of the diet on behavior. It remains a very intriguing area of applied animal behavior. However, there is at present no evidence that preservatives or food coloring have any effect on behavior. Supplements that might be useful in the treatment of behavior problems are discussed in Chapter 9.

Fatty acids

There has been renewed interest in the fatty acids and their effects on behavior. While the essential fatty acids (cis-linoleic acid in the dog and cis-linoleic acid and arachidonic acid in the cat) are, by definition, essential for life, attention has been focused recently on the long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, specifically docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and, to a lesser extent eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA). DHA, while technically not considered essential, is important in neural and retinal development, neurotransmission, and protection against oxidative stress.9 EPA is an important anti-inflammatory agent that has been used primarily in the treatment of atopic dermatitis and for degenerative joint disease.10

Supplementation with DHA-rich dietary oils results in higher circulating levels of DHA,11 which is important because this cannot be easily achieved with shorter-chain omega-3 fatty acids such as alpha-linolenic acid, especially after weaning.12 Because of the inefficiency in converting alpha-linolenic acid to EPA and DHA, supplementing with the preformed dietary long-chain fatty acids, typically derived from fish oils, is preferred.13 There is considerable interest in the effects of supplementation of diets with DHA (and EPA) during gestation, lactation, and even in the postweaning period.14

In addition to retinal function and brain development, an improvement in the performance of memory and learning tasks, trainability, cognitive function, psychomotor function, immunologic, and problem-solving skills has been demonstrated in puppies with DHA supplementation.12,13 Therefore, there may be benefits for supplementing pet diets with DHA-rich fatty acids during gestation, lactation, the immediate postweaning period to 16 weeks of age, as well as in senior pets with cognitive dysfunction. DHA can be provided in diets specifically formulated for this purpose, or with appropriate dietary supplements.

Diagnosis of diet-related behavior problems

The hypothesis of high-protein, preservative-rich, dry diets or food ingredients contributing to behavior problems can be tested by feeding a trial diet for 7–10 days, watching for changes, and then challenging the patient with the original diet to determine if the problem recurs. Prior to trial with any new test diet, it is essential that there are no abnormalities on physical examination and that routine blood and urine tests are normal. In addition to low-protein trials, by using a homemade novel protein diet, preservatives and additives can be avoided and the single protein source may help to identify pets with adverse food reactions (although a trial for dietary allergy or intolerance may require 8 weeks or longer, and does require the selection of novel proteins only).15

This diet is not nutritionally balanced but should not be problematic for the 7–10 days in which the low-protein trial is being conducted. When testing for 8 weeks or longer in the evaluation of an adverse food reaction, a homemade diet is likely sufficient unless being fed to a puppy/kitten, or to pregnant or lactating animals. In these cases, a nutritionist should be consulted to formulate a diet that is nutritionally balanced while still being hypoallergenic for that specific animal. It is important to realize that some retail pet foods marketed as hypoallergenic have been found to contain known food allergens, so client compliance with veterinary recommendations is paramount to conducting a suitable elimination diet trial for adverse food reactions.16

Some research has also focused on the use of biomarkers for diagnosis of behavior problems, particularly aggression. For example, dogs with social conflict-related aggression may have significantly lower serotonin levels and significantly higher cortisol measures than control dogs.3 This doesn’t yet allow us to predict which dogs will eventually become aggressive, those dogs that will best respond to drug therapy, or even allow a diagnosis of aggression in dogs, but it does further our understanding of the potential biomedical basis for canine aggression.

Prevention of diet-related behavior problems

Epigenetics is the study of heritable changes in phenotype or gene expression due to mechanisms other than DNA mutations. Diet is one of the more impactful nongenome catalysts in this regard, and the interaction of nutrients with genetic and epigenetic traits is sometimes referred to as nutritional genomics, or nutrigenomics. In this way, nutrients may affect the expression of a certain genetic trait, make a pet more or less susceptible to disease processes, and have a variety of other positive or negative effects. This will become progressively more important in veterinary medicine as researchers find links between genetic profiles and disease, the impact of diet on epigenetic inheritance, and the effects of diet on gene transcription and translation rates.17

There may also be wholly genetic factors associated with diet and there is some anecdotal evidence that behavior problems due to some dietary ingredients may be familial. It has been suggested that some breeds seem to react to preservatives (e.g., Cavalier King Charles spaniel), some to exorphines (golden retrievers) and others to serotonin-influencing factors of different meat proteins.18 Research remains to be done to confirm these possibilities. Neutering animals with these dietary idiosyncrasies will lessen the contribution of any hereditary factors to the breed gene pool.

Case example

Although the improvement in behavior was likely due to resolution of an underlying adverse food reaction and the removal of corticosteroids (both of which may have contributed to his irritability),19 the owners believed that the behavioral changes were directly related to the beef and milk which they believed were “adulterated” with hormones and antibiotics.

Ingestive behavior problems

Ingestive behavior problems may be related to management issues (e.g., obesity); undesirable but normal behaviors (e.g., food stealing/garbage raiding); medically induced ingestive disorders (polyphagia due to corticosteroid administration or hyperadrenocorticism; environmental licking due to gastrointestinal upset); and abnormal behaviors such as picas. In cats, ingestive problems were the third most common reason for referral at one behavior practice, comprising 4.3% of 736 referral cases (of which 40% were Siamese cats with pica).20In dogs, abnormal ingestive behaviors (pica, coprophagia, hyperphagia, anorexia, excessive chewing and licking) represented 1.4% of 1644 referral cases.21

Obesity

Obesity is the most common nutritional disorder in North America.22 A sad statistic is that over 25% of dogs in North America are overweight.23 A recent UK study estimated that 48% of cats were overweight or obese.24 It is likely that obese pets suffer more from osteoarthritis, respiratory distress, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, decreased heat tolerance, and some forms of cancer and are at increased risk if undergoing anesthesia or surgery.25 Today, more than ever, pets are being “killed with kindness” as their owners allow them to become obese.

Obesity becomes more common as pets get older. Females are more prone to obesity than males, and neutered pets are more likely to become obese than intact pets.26 Genetic factors are also contributory.27 Labrador retrievers, Cocker spaniels, collies, dachshunds, beagles, Basset hounds, miniature schnauzers, Shetland sheepdogs, and some terriers are more prone to obesity than other breeds. Some breeds, most notably the German shepherd dog, boxer, whippet and, greyhound, actually have a lower incidence of obesity. Although genetics plays a role, clearly the most important factors leading to obesity are providing pets with excessive calories and inadequate physical activity.28 In cats, the most common predictors of being overweight were being male, neutered, middle-aged, mixed-breed, and apartment-dwelling.29 Obesity is rarely seen in wild animals and only infrequently in working dogs. It is the household pet, rarely exercised, confined to the home, and fed a high-quality diet, that is most prone to obesity.

The pet food industry markets highly palatable, high-calorie diets with a focus on the consumer.30 The supplement market contributes biscuit treats and fatty acid supplements that are usually calorie-dense. The owner, with a strong emotional bond to the pet, wants to provide a healthy, tasty meal that the pet readily devours. The veterinarian, in the position of health-concerned middleperson, must counsel the owner about what is really in the best interests of the pet.

Diagnosis and prognosis

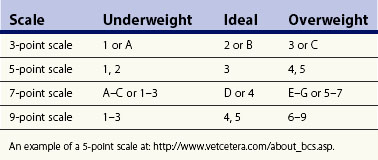

Pets are considered overweight when they are 5–10% above their ideal weight, and obese when they are 20% more than their ideal weight, although there is quite a bit of variability in how the terms are defined. This can be assessed by visual inspection (fat covering of ribs) and palpation. Body condition scoring (BCS) uses a scale to evaluate body fat subjectively and semiquantitatively by visual assessment and palpation. There are four numeric scoring systems for BCS – a 3-point scale, a 5-point scale, a 7-point scale, and a 9-point scale – and all are useful for this purpose, as long as assessments are consistent. In general, with the 9-point scale, each 1-point change from ideal represents an increase or decrease of 5%; with the 5-point scale, each point represents a 10% change. BCS should be evaluated and appropriate dietary recommendations discussed at each visit. To avoid confusion between the four scales, it is best to express the pet’s score as a numerator and the scale as a denominator (e.g., 3/3, 4/5, or E/G or 6/7, or 7/9) (Table 10.1).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree