Chapter 6 Exodontics

GENERAL COMMENTS

• Teeth should not be sacrificed unnecessarily. In years past, when veterinary dentistry was taught in veterinary curricula, exodontics was one of the primary subjects. Students learned how and where to trephine and repel equine teeth. Entire books were devoted to equine dentistry, such as L.A. Merillat’s Animal Dentistry and Disease of the Mouth published in 1911 by Alexander Eger. As the usefulness of the horse in industry declined, equine dentistry was not emphasized as much in the veterinary curriculum. As current practitioners endeavor to render good dental care for their patients, they should bear in mind that exodontics is the area of dentistry they should practice as infrequently as possible. Most veterinarians are sensitized to the term euthanasia and do not like to perform such a procedure wantonly. It may be helpful to use the term euthanasia interchangeably with the word extraction. That way, every time a tooth euthanasia, or “toothanasia,” is performed, more sensitivity will be manifest, and the practitioner will look for other, more positive alternatives.

• When extractions are indicated, however, many animals will have greatly improved oral health and a better quality of life if extractions are performed properly.

• Teeth normally are held in the alveolar bone by the periodontal ligament. When teeth are removed, the periodontal ligament must be stretched and then broken or torn. If this is accomplished properly, without the complication of an expansion fracture of the alveolus, the rest of the extraction process is atraumatic.

• Preoperatively, the practitioner should consider the advisability of a preanesthetic hematologic database, as well as other laboratory tests indicated by history or preprocedural medical examination.

• The client’s approval should be obtained for the extent of treatment, potential complications, the cost anticipated by the clinician, and a plan of action in the event that unanticipated pathology is discovered during the procedure.

• Additionally, local anesthesia should be considered, to decrease the amount of anesthetic medication needed to maintain a surgical plane of anesthesia and for intraoperative and postoperative relief of pain (see Chapter 12).

• A radiograph should be taken before extractions to evaluate health of the alveolar bone, visibility of the periodontal ligament, variations in root anatomy, presence of ankylosis as seen by decreased visibility of periodontal space, sclerosis as seen by increased density of alveolar bone, or root resorption. This information helps determine the justification for, complexity of, and treatment modality for the intended extraction.

• Good accessibility and exposure to the surgical site may require changing the patient’s position during the procedure.

• Good visibility facilitates the procedure. Bright lighting, magnification, suction, use of an air-and-water syringe, and relative position of the clinician and patient are all factors affecting visibility.

• Buccal gingival flaps are used appropriately to improve visibility and to expedite atraumatic access to and removal of solid teeth requiring extraction.

• The patient should be under a general anesthetic. A secured endotracheal tube with inflated cuff and gauze packed at the back of the pharynx will help prevent blood and debris from entering the airway and esophagus. A pad or towel beneath the head will cushion the head from pressure during the procedure. Ophthalmic ointment in the eyes will protect them from drying, and a drape or cloth covering the face will protect the face from soiling and the eyes from the operative light, foreign objects, and debris.

• A #11 scalpel blade is used to sever the epithelial attachment circumferentially around the tooth. A sharp elevator of appropriate size and curvature should be used to match the curvature of the root of the tooth intended for extraction. The elevator is grasped with the butt of the handle seated in the palm of the clinician’s hand, and the index finger is placed as close to the tip as possible to protect the tissues in case of instrument slippage.

• The patient’s head needs to be supported properly. During maxillary tooth extractions, the patient’s head is cradled over the bridge of the maxillary bone with the palm of the free hand. With small dogs and cats, the entire head may be cradled in the palm of the hand during caudal maxillary tooth extractions.

• During mandibular tooth extractions, the jaw can be cradled in the palm of the free hand, or the individual side can be grasped between the thumb and forefinger. This support helps prevent jaw fracture by neutralizing pressure applied during extraction. It also helps prevent facial nerve damage, due to pressure on the head, if the head is resting on a hard table.

• Gentle tissue handling is important to minimize trauma and to allow rapid healing of both hard and soft tissues.

• Most states consider extractions as surgery and permit only licensed veterinarians to perform exodontia. A minority of states (nine states in 2003) also allow veterinary technicians to perform extractions. The American Veterinary Dental College, in a position statement dated April 5, 1998,1 has taken the position that only licensed veterinarians may perform extractions.

Indications

• As a general principle, with permission from the client, any diseased tooth that is not contributing to function is a likely candidate for extraction.2

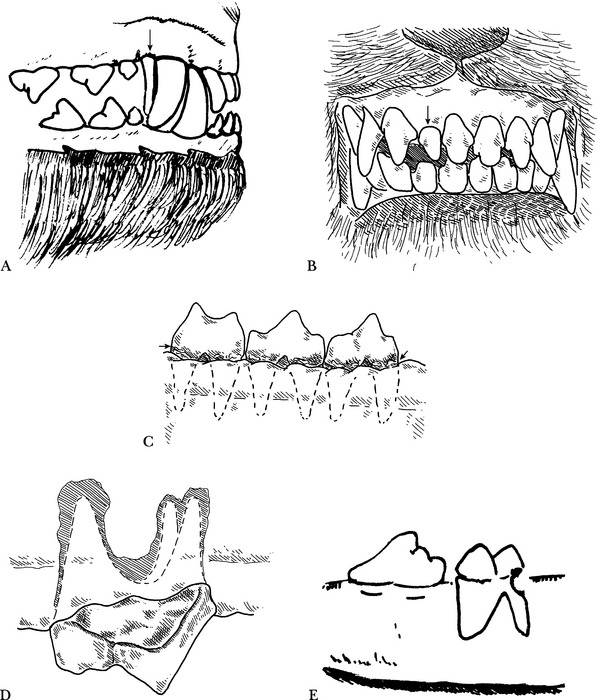

• Persistent primary teeth (Fig. 6-1, A, arrow). Two homologous teeth should never be in the mouth at the same time. If a practitioner identifies an adult tooth erupting and the primary tooth is not exfoliating naturally, it is time to extract the primary tooth.

• Interceptive orthodontics. Primary teeth are extracted when the mandible or the facial maxillary structures are not developing appropriately and a malevolent interlock exists, interfering with normal jaw development. Supernumerary teeth (Fig. 6-1, B, arrow) are extracted when they cause crowding or interfere with occlusion and periodontal health.

• Malocclusion or malpositioned teeth, if orthodontics, occlusal equilibration, or other corrective techniques are declined by the client.

• Periodontal disease, if the periodontium cannot be restored, or if the client does not commit to a combination of the necessary home and periodic professional care (Fig. 6-1, C, arrow).

• Nonvital teeth, or fractured crowns with pulp exposure when root canal therapy will be unsuccessful due to extensive periapical abscess formation (Fig. 6-1, D), or if the client declines endodontic treatment.

• Teeth that have structural damage, for which restoration is not feasible because of the extent, type of destruction, or for economic factors.

• Teeth in a fracture line that interferes with bone fracture repair or healing. Teeth in a fracture line may or may not require extraction.2,3

• Dental or oral disease, when the client desires a possibly less expensive but definitive treatment. Note: extraction is not necessarily the easiest or least expensive method of treatment. An example of a time-intensive extraction would be an otherwise healthy, stable canine tooth or carnassial tooth that has been recently fractured. The procedure becomes more time intensive and expensive if the extraction would leave the mandible severely weakened, thus requiring a protective bone graft.

Contraindications

• Malignant conditions, when the patient is undergoing radiation or chemotherapy that would inhibit healing.

Objectives

• Controlled force should be used when extracting teeth. Patience is prudent for successful extractions.

• A tooth should be extracted completely, with as little trauma to the oral tissues and bone as possible.

• All the tooth’s roots should be extracted, unless there is ankylosis of roots and no sign of infection or inflammatory disease. This is especially true in cats.

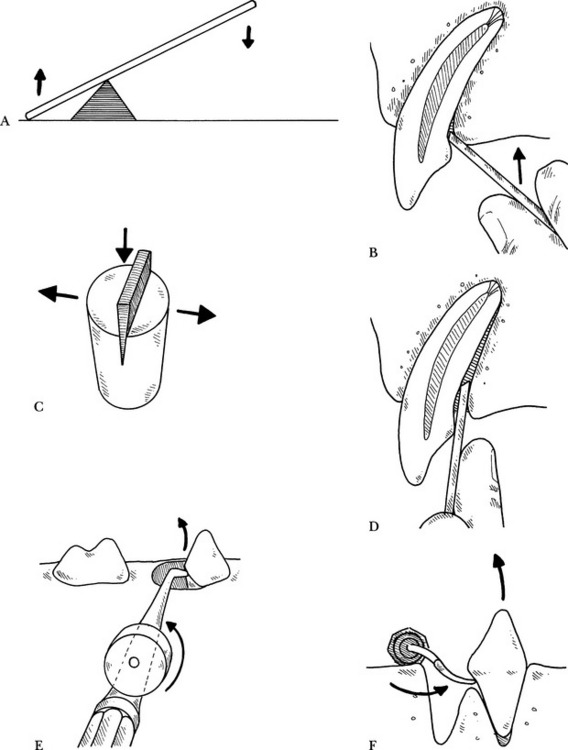

• A scalpel blade is used first to sever the epithelial attachment to the tooth. Surgical elevators are used as levers to break down the periodontal ligament. Three basic types of lever are involved4:

• If the tooth root has not been displaced by the surgical elevator, extraction forceps are used to lift the tooth out of the socket after the periodontal ligament has been torn free.

Materials

Canine Extraction Pack

• Number 4 or 6 round bur; 701L, 557L, 1557L, or 1558L cross-cut cutting burs in a low-speed or high-speed handpiece with irrigation.

• Suture material: 3-0, 4-0, and 5-0 resorbable suture, reverse-cutting needle or taper swaged-on needle.

• Monocryl (poliglecaprone 25, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ), Vicryl (polyglactin 910, Ethicon), Dexon II (polyglycolic acid, U.S. Surgical, Norwalk, Conn.), Maxon (Davis & Geck, Manati PR), chromic catgut.

• Consil (Nutramax Laboratories, Inc., Edgewood, Md.), or Collaplug (Zimmer Dental, Carlsbad, Calif.).

Feline Extraction Pack

• Number 7 wax spatula, Molt #2 periosteal elevator, or EX9C (Cislak Manufacturing, Glenview, Ill.).

• Root elevators: 301S or other feline elevators, 2-mm elevator, 3-mm curved luxator, 100C (Cislak).

• Numbers 330, 2, 4, 699, and 701 cutting burs with low-speed or high-speed handpiece with irrigation.

SIMPLE EXTRACTION OF SINGLE-ROOTED TEETH

Incisors, First Premolars, and Mandibular Third Molars

Technique

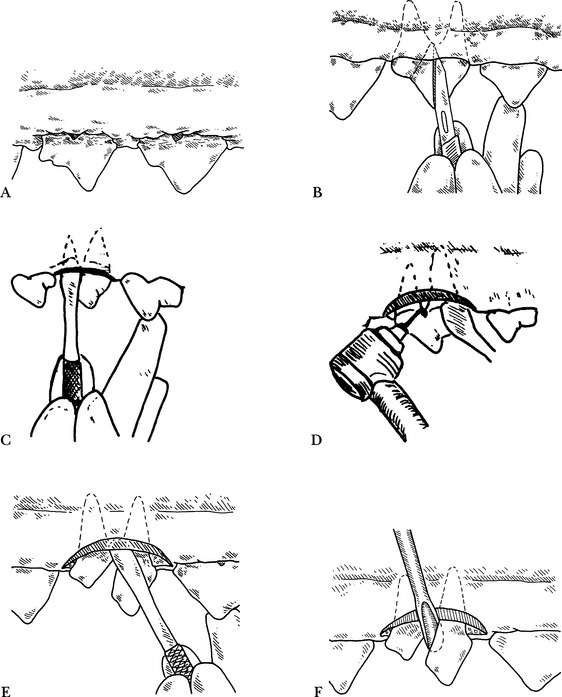

Step 1 —A radiograph is taken, and the tooth is evaluated for root structure, periodontal ligament health, and surrounding bone (Fig. 6-3, A).

Step 2 —The gingival attachment is incised by inserting a #11 scalpel blade into the sulcus and severing the gingival attachment circumferentially around the tooth (Fig. 6-3, B). Luxators and winged elevators can be used to cut the periodontal ligament. They are placed in the periodontal ligament space and with apical pressure, while encircling the root, the periodontal ligament is cut and the instrument advanced apically.

Step 3 —A surgical elevator, or Molt #9 periosteal elevator, is used to break down the periodontal ligament by alternately stretching and compressing it. The tip of the elevator is inserted between the tooth and the alveolar crest at a slight angle to the tooth, with the concave side facing the tooth. This utilizes the elevator as a wedge lever. The instrument is forced apically, then rotated slightly until tension is exerted on the periodontal ligament. This position is held for 5 to 10 seconds. The elevator is gently moved around the circumference of the tooth in this fashion and gradually advanced apically (Fig. 6-3, C). Loosening of the tooth in the socket will be noticed as the periodontal ligament is stretched and torn. Hemorrhage from the torn periodontal ligament will assist in elevating the root.

• Alternately placing the elevator mesially and then distally, while maintaining rotation as well as apical pressure on the tooth, will result in further stretching and tearing of the remaining periodontal attachments. At this time the elevator can often be used as a first-class lever to lift the tooth out of the socket (Fig. 6-3, D). A notch can be made at the neck of the tooth with a bur, to gain additional purchase when using the elevator as a first-class lever (Fig. 6-3, E).

• The luxator can also be placed as a wedge lever; then rather than twisting or torquing the instrument against the tooth, the handle is moved side to side to create a cutting action at the luxator tip.

Step 4 —The loosened tooth is grasped with extraction forceps as close to the gum line as possible. The tooth can be rotated slightly on its long axis with a steady pull to remove the tooth from its socket. Note: do not use force. If the tooth is not easily displaced, continue elevating it with either the wedge or first-class lever technique, intermittently using the extraction forceps, if necessary.

Step 5 —The extracted tooth should be examined to ensure that the entire root has been extracted. If the root has broken into pieces, a radiograph is indicated to determine the number of fragments and where they are located.

Step 6 —If there were retained fragments, additional radiographs, as necessary, including a postoperative radiograph, are taken to confirm that the entire root has been removed.

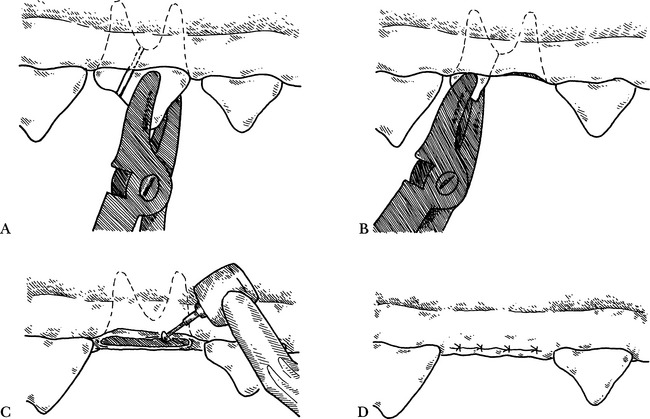

Step 7 —The alveolus is debrided with a spoon-(Fig. 6-4, A) or bone curette (Fig. 6-4, B) to remove any infected granulation tissue, debris, pus, and necrotic bone. The curette is placed at the apex and a scraping, pulling motion is used from the apex toward the rim of the socket.

Step 8 —The crest of the alveolar bone may need to be reduced to facilitate suturing. This can be done by using a rongeur (Fig. 6-4, C), a bone rasp, or a round bur with water spray. This step is performed to increase chances of primary tissue apposition, prevent fenestrations of soft tissue by sharp bony edges, and hasten the autoosseous remodeling period.5

Step 9 —The extraction site is lavaged gently with saline or dilute chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine solution. A blood clot is left in the alveolus. A syringe with an 18-gauge needle creates adequate pressure.

Step 10 (Optional)—If enhanced healing is desired, various products may be used. The alveolus can be packed with synthetic bone graft material (Consil, Nutramax Laboratories Inc.) or autogenous bone, as indicated. Tetracycline powder was once recommended for placement in extraction sites.6 This treatment modality has, in most cases, been replaced by debridement and irrigation with physiologic saline solution or dilute solutions of antimicrobial agents such as chlorhexidine or iodine.

Step 11 —Digitally compress the extraction area with gauze. This helps collapse the alveolar socket, reduce hemorrhage, and appose gingival tissues. Suturing may not be necessary after this step when extracting very small teeth and if minimal damage has occurred to the periodontal tissues.

Step 12 —The gingiva is best sutured using a reverse-cutting or a taper needle and 3-0 or 4-0 absorbable suture material (Fig. 6-4, D).

NONSURGICAL EXTRACTION OF TEETH WITH MULTIPLE ROOTS

• The multirooted teeth in the dog are the maxillary second, third, and fourth premolars; maxillary first and second molars; mandibular second, third, and fourth premolars; and mandibular first and second molars.

• In the cat: the multirooted teeth are the maxillary third and fourth premolars; mandibular third and fourth premolars; and mandibular first molar.

Indications

• Premolars and molars that are partially mobile secondary to periodontal disease or advanced periapical abscess formation (Fig. 6-5, A). These may include the maxillary fourth premolar and the upper and lower first and second molars.

• Extraction of crowded or rotated premolars in a brachycephalic dog to preserve the periodontal health of adjacent teeth.

Technique

Step 1 —The gingival attachment is incised around the tooth with an elevator or scalpel blade (Fig. 6-5, B).

Step 2 —A radiograph is taken and evaluated to determine whether the tooth can be extracted easily. If it can, it is extracted using those techniques and principles of the simple single-root extraction, with elevation proceeding around each root until the remaining periodontal attachments are loosened.

• If the tooth is mobile, the roots are not seen on radiograph to be unfavorably shaped or oriented, the elevator can be placed in the furcation perpendicular to the long axis of the tooth to gain good purchase, and coronal pressure is applied to remove the tooth, providing the roots are not divergent or hooked. Care must be taken that all gingiva has been cut away from the tooth. If extraction forceps are used, each root must be loosened completely before extraction. Minimal twisting is used to remove the tooth. This reduces the risk of root fracture. If elevation cannot be performed easily, the tooth should be sectioned, separating each root.

Step 3 —Using a periosteal elevator, the gingiva is elevated from the tooth and retracted, unless gingival recession is significant (Fig. 6-5, C).

Step 4 —A cross-cut fissure bur is used in either a high-speed or low-speed handpiece to section the tooth. Sectioning is performed taking the shortest, straightest pathway, starting from the furcation and cutting coronally (Fig. 6-5, D). This leaves each root separate and isolated. A water spray is used during sectioning to avoid heat necrosis of adjacent teeth and bone.

Step 5 —Each root is elevated as in a simple single-root extraction (Fig. 6-5, E). The elevator can also be placed perpendicular to the long axis of the tooth at the furcation between the roots, and rotated slightly and held for 5 to 10 seconds to distract and loosen the roots (Fig. 6-5, F). Each root is loosened progressively, using adjacent roots for leverage when possible. If one root is more solid, the other root(s) can be removed first to allow easier elevation along the interradicular surface of the solid root.

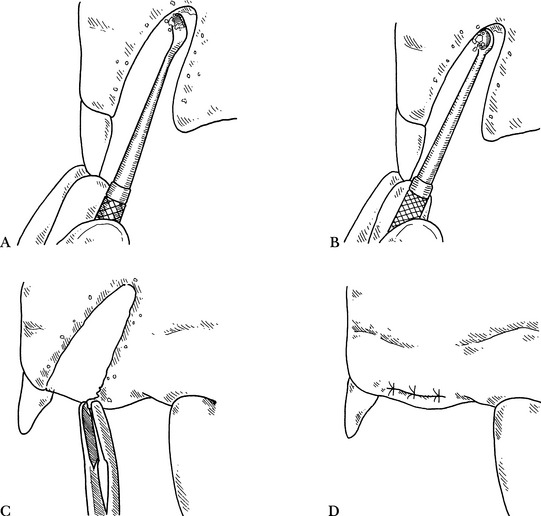

Step 6 —Once all roots are mobile in the sockets, each is extracted using extraction forceps (Fig. 6-6, A and B).

Step 7 —The extraction segments are examined, and if the entire root cannot be accounted for, a radiograph should be taken, any remaining fragments identified and removed, and a postoperative radiograph taken.

Step 9 —Irregular edges of the alveolar crest are smoothed using a rongeur, bone rasp, or bur in a handpiece (Fig. 6-6, C).

Step 10 —The extraction site is lavaged with saline or a dilute chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine solution.

Step 11 (Optional)—The socket can be packed with synthetic bone or polylactic acid granules or cube as discussed in the single-root technique.

Step 13 —The gingiva is sutured, tension-free, over the extraction site with 3-0 or 4-0 absorbable suture (Fig. 6-6, D).

Maxillary Fourth Premolar

Additional Considerations

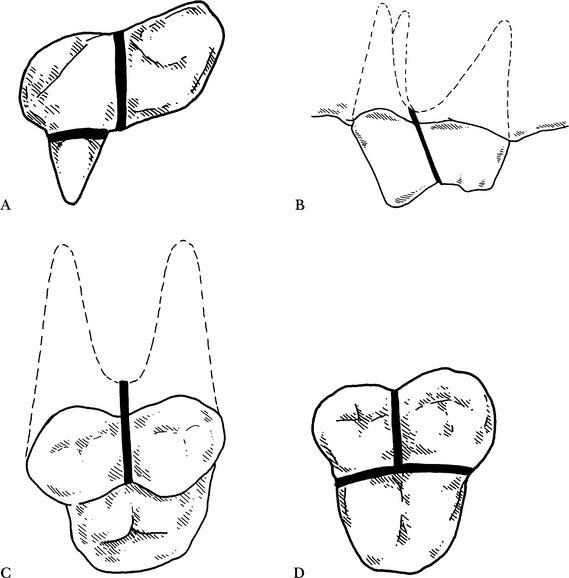

• The gingival attachment is separated, starting from the furcation and cutting coronally, and each root is separated using a cross-cut fissure bur in a handpiece (Fig. 6-7, A).

• The palatine root is separated by cutting in the fissure created by the base of the large mesiobuccal cusp and the palatine cusp.

• The mesiobuccal and distal roots are separated by cutting between the two large cusps in a straight line from the furcation (Fig. 6-7, B).

Maxillary First and Second Molar in the Dog

Additional Comments

• The mesial and distal roots are separated by cutting coronally, starting at the furcation and cutting toward the cusps (Fig. 6-7, C).

Surgical Extraction Technique

General Comments

• This technique is used for difficult extractions in which tooth size, number of roots, root anatomy, or pathology seen on preoperative radiographs indicate potential for complications or increased difficulty in extraction.

• The process is more involved and should not be used if simple elevation will suffice. Surgical extraction techniques, however, can expedite difficult extractions and will save time by reducing the frequency of root fracture, providing better exposure, better access for root elevation, and improved postoperative healing as a result of a less traumatic procedure.

Indications

• Larger, solid, single or multirooted teeth that require extraction, when simple elevation techniques are insufficient for adequate removal.

• Generally, the canine teeth and carnassial teeth in the dog affected by endodontic or early periodontal disease, where other treatment options are not feasible or declined by the client.

Technique

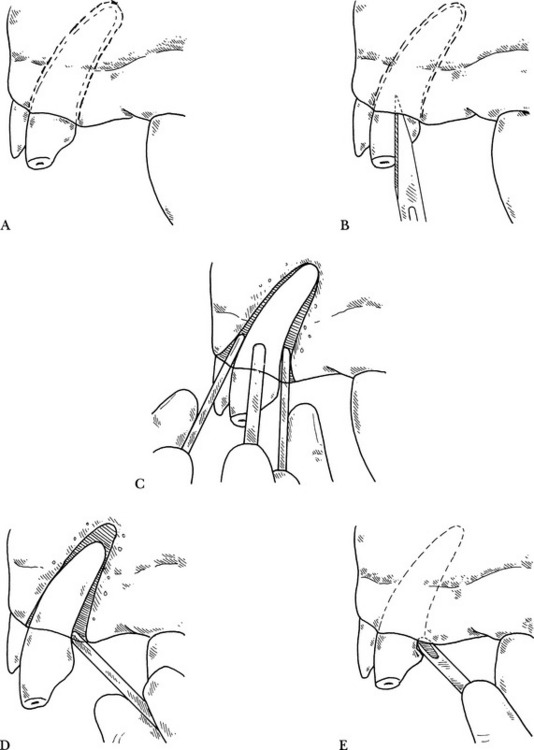

Step 2 —The gingival attachment around the tooth is incised with a scalpel blade or surgical knife (Fig. 6-8, A). A small excavator can be used in cats.

Step 3 —A buccal mucoperiosteal (full-thickness) flap is created over the tooth with one or more vertical releasing incisions. Cuts making the releasing incisions should be made with a single motion, down to the bone. Apically diverging releasing incisions are made over healthy tissue one tooth mesial and distal to the tooth to be extracted (Fig. 6-8, B). This permits adequate circulation to the flap. (In cats with multiple extractions, the entire quadrant may be exposed with one large gingival flap.)

Step 4 —It may be necessary to elevate the flap apical to the end of the juga (bony prominence covering the root). The flap should be elevated carefully from the buccal bone, mesial to distal, with a periosteal elevator (Fig. 6-8, C). The lingual or palatal gingival tissue should be elevated as an envelope flap to expose the alveolar crest.

Step 5 —A cutting bur with water cooling is used to reduce the level of the alveolar bone buccally, mesially, and distally as necessary, as much as 1 to 2 mm in a cat or 3 to 5 mm in a dog (Fig. 6-8, D). The bone height in the coronal furcation area can be reduced, also. With canine teeth, the outline of the juga is cut through the bone with the bur. The entire buccal apical surface of the root does not always have to be exposed. This osseous cut frees the buccal plate from the rest of the facial bone. An elevator can be used to remove the detached bony plate (see p. 314).

Step 6 (Optional)—If desired, a ledge can be drilled into the tooth at the rostral and caudal aspect of the tooth, at the junction of the alveolar crest and the root. This allows for elevator purchase for dislocating and extruding the intended root from its alveolus.

Step 7 —If the tooth is multirooted, it should be sectioned as described on p. 302 and illustrated in Fig. 6-8, E.

Step 8 —An elevator can now be used as a wedge around the mesial, lingual, or palatal and distal surfaces, as in a simple extraction, to stretch the periodontal ligament or break the ankylosis of the root structure. Remember to hold the elevator with a slight rotating, torquing force for 10 to 30 seconds wherever it is placed. Note: do not use the elevator vertically between crown pieces. This may lead to root fracture or a distraction mandibular fracture. The fingers of the other hand should support the mandible while elevating each mandibular root.

Step 9 —The elevator can be placed perpendicular to the long axis of the tooth at the furcation area between roots and between the mesial or distal root and the adjacent tooth as a wheel-and-axle lever or as a first-class lever to gradually stretch the periodontal ligament. Finesse and patience while freeing each root will help achieve a successful extraction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree