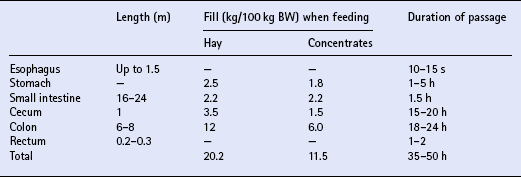

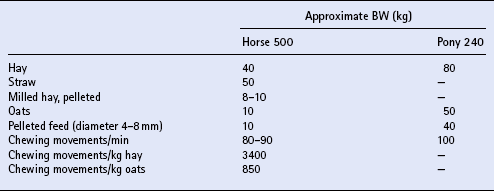

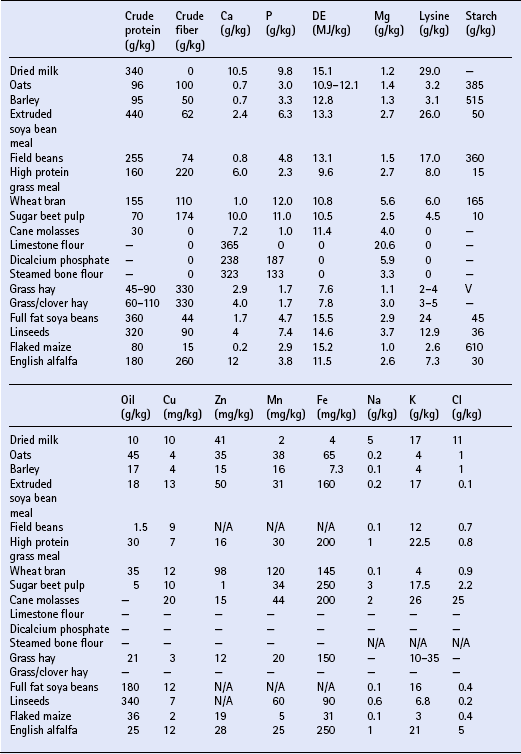

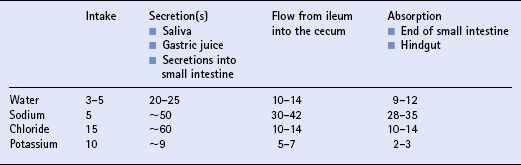

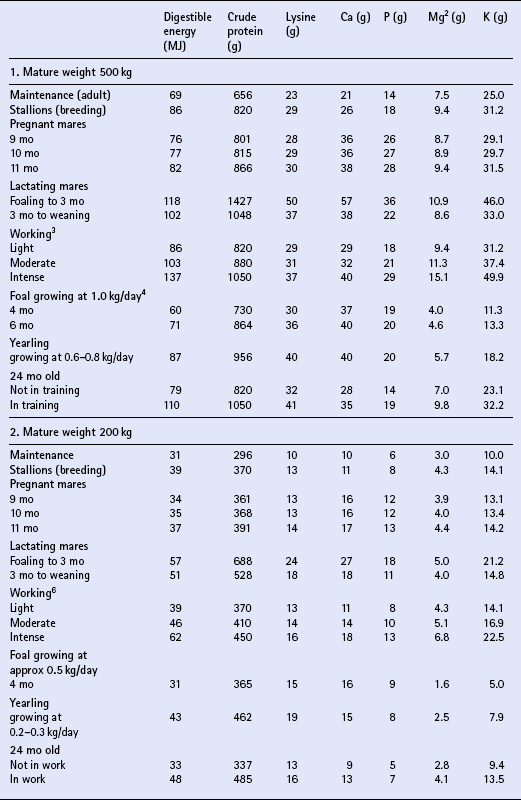

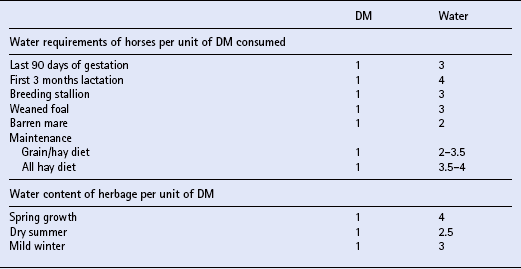

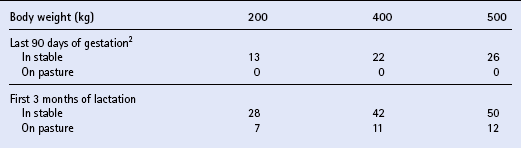

Chapter 3 Utilization of dietary sources Calcium, phosphorus and magnesium Sodium, potassium and chloride Possible clinical signs associated with deficiencies Possible clinical signs associated with excess PRACTICAL NUTRITION AND PRACTICAL RATION FORMULATION FEEDING THE PREGNANT/LACTATING MARE Colostrum and neonatal feeding Sodium, potassium and chloride requirements for pregnant, lactating and growing horses Effects of dietary excesses and deficiencies NUTRITION AND MANAGEMENT IN THE FIELD NUTRITIONAL ASPECTS OF METABOLIC DISEASES However, many of the equine nutritional practices currently employed have not changed significantly from those followed hundreds of years ago, although the nature and composition of the basic feedstuffs has changed in some instances. The most significant change in the twentieth century was probably the introduction of pelleted feeds around 1920. These became popular in the 1960s when competition, increased knowledge, more ethical companies and government regulations resulted in the evolution of good quality, commercial, compound feeds. Domestication and our increasing demand for horses to perform repeatedly have resulted in energy requirements that, for some horses, are above those able to be provided by their more “natural” diet of fresh forage. Cereals provide more net energy than hay, which in turn provides more than twice the net or usable energy of straw. However, the upper part of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) has a relatively small capacity and the horse has digestive and metabolic limitations to high grain, starch and sugar based diets. Large grain meals may overwhelm the digestive capacity of the stomach and small intestine leading to the rapid fermentation of the grain carbohydrate in the hindgut. This potentially can result in one of a number of disorders including colic, diarrhea and laminitis. Table 3.1 provides figures for the typical composition of some common feedstuffs. Individual samples may vary within a range and, for complete accuracy when evaluating a dietary regimen, individual analyses must be undertaken. Pasture and hay analyses vary according to season, soil type, geographic location and other variables such as harvest date. For accuracy, a number of actual representative forage (fresh or preserved) samples must be analyzed when reliable results are required. Table 3.1 Guide to the typical composition of common feedstuffs (assuming 880g DM/kg), in part derived from the NRC 1 N/A, data not available; V, variable. 1National Research Council, NRC (1989) Nutrient Requirements of Horses, 5th ed, National Academy Press, Washington DC. Oats are the traditional cereal fed to horses in work. They contain significantly higher fiber and lower starch levels than most other cereals and the nature of their starch particles helps to promote a high pre-cecal starch digestibility in contrast, for example, to corn and barley. As with all cereals and cereal by-products, oats provide a low level of calcium and a moderate level of phosphorus (which may be bound in phytate compounds, reducing its availability), giving a reversed calcium to phosphorus ratio (q.v.). Also, in common with most cereals, the level of the essential amino acid lysine is relatively low. There are now varieties of oat produced without husks, colloquially often called naked oats. They have a better amino acid profile, higher oil levels, and thus considerably higher energy levels than the husked varieties. Horses have been shown to be able to digest and utilize high amounts of oil, but for practical purposes approximately 0.75–1 g of oil/kg BW/day may be considered to be the upper limit. Levels of 5–8% in the total diet are more common in some high performing horses and many performance horses can be fed up to 100 mL/100 kg BW daily in divided doses without any problems provided that it has been introduced gradually, is not rancid, the horse requires such an energy intake, additional vitamin E is provided and the overall diet is re-balanced. Supplemental fat or oil diets can be supplied in four main ways: 1. As an oil supplemented, manufactured diet. The advantage here is that such diets should be balanced with respect to the protein, vitamin and mineral intake that they provide when fed with forage (and salt as required). This can be a simple, practical and convenient way to feed high oil diets. 2. High oil supplemental feedstuffs, such as rice bran, which are also high in fiber and usually low in starch. However, many of the rice brans available have the same disadvantages as wheat bran in that they have a very imbalanced calcium-phosphorus content. 3. Supplemental animal fat. Many horses find most animal fats to be unpalatable and these fats seem often to be more likely to cause digestive upsets. Their use is not to be recommended. 4. Supplemental vegetable oils. The exact type of oil that may be preferred will depend on the individual horse and the nature of the processing to which the oil has been subjected. Corn oil and soy oil are probably the most commonly used vegetable oils in Europe. 1. Increased mobilization of free fatty acids (FFA) and increased speed of mobilization; increased speed of uptake of FFA into muscle—often considered to be rate limiting. 2. A glycogen sparing effect so that fatigue is delayed and performance improved (this could be especially important in endurance activities). 3. Increased high intensity exercise capacity. 4. In horses with a high energy demand, helping to reduce feed volume so that the roughage intake can be maintained (oils have also been suggested to help reduce the extent of bacterial dysfermentations in the stomach and small intestine). Linoleic acid and alpha-linolenic acid are considered dietary essential fatty acids. However, no evidence of deficiency has been described for the horse and it must be assumed that a normal diet of cereal grains and natural forage, or of pasture herbage, will provide the dietary requirements. 1. The nutrient levels in the selected forage, and thus the percentage of the horse’s total daily nutrient requirements that will be met through the fiber source. 2. The effect that forage may have on other aspects of the horse’s health, especially the respiratory system. Hay is the most commonly used long fiber source and may be divided into several types. Legume hay (usually alfalfa or lucerne, clover or sainfoin) has, due to nitrogen-fixing properties, higher protein levels than seed or meadow hay. Legume hay may be grown as a pure stand, but can be difficult to dry in cool wet climates as the stalks are very moist and thick so that cutting is often left until later in the season, when temperatures increase. However, by then the hay may have become very mature and stalky, with low energy and digestibility values. An exception to this is alfalfa, which can be cut earlier, barn dried and packaged in a short chopped form in plastic-covered bales. Clover and sainfoin are commonly mixed with grass species such as timothy to make conventional hay, but care must be taken with the leys, as competition between the species will alter the relative proportions over a number of years. Some larger horse keepers now find it economical to use silage. The rapid pH drop, the greater water activity, the decrease in available oxygen and soluble carbohydrates as fermentation progresses all can help inhibit the development of fungal spores. There are, however, several important factors to be considered before using silage. Correct maintenance of the hydroponic unit is vital to ensure optimal conditions for germination—usually 20/24 h of light and a temperature of 19–20°C. Routine hygiene is important to prevent the build-up of mold spores. The barley seeds used should be of the highest quality and must not be treated with mercurial or other seed dressings. The feeding of hydroponic barley is not commonly practiced today. Oil extraction and “roasting” of high oil seeds is an industrial process. The resultant oils extracted are then available for use in human or animal feeds, depending upon the degree of refinement. Caution should be exercised as to whether the analyses are given on the fresh as fed material, or on a dry matter basis. “Dry matter” basis refers to the feed or forage after the moisture has been taken out, whereas the term “as fed” refers to a feed as it would be fed to a horse. Most concentrate feeds such as cereals, cubes, pellets, etc., contain approximately 10% moisture with a dry matter content of 88–92% and fresh forage from 20% to 60%. It is important to realize that only the dry matter contains nutrients, so more feed will need to be fed, on an as fed basis, to match requirements if the feed contains more water. Box 3.1 gives suggestions for routine analyses in order to assess general feed quality and major nutrient levels. In special circumstances, more detailed analyses will be required. The empty alimentary tract accounts for about 5% of the total BW of a horse. The weight of the gut contents varies according to feeding, from 5% (concentrate) to 10% (roughage). In the small intestine, digestion is primarily by the body’s own enzymes, while in the voluminous large intestine the feed components are fermented by microorganisms. It is important to appreciate, however, that some fermentation will occur in the stomach and the small intestine. The approximate sizes of the various sections of the gastrointestinal tract are shown in Table 3.2. The duration of feed intake ( Table 3.3) depends on the type of feed and the size of the animal. By feeding mainly concentrates, the time taken to ingest the feed and the number of chewing movements are greatly reduced. This may lead to a change in behavioral patterns: for example, animals may bite and lick objects within their reach. Horses should be fed sufficient amounts of roughage (preferably long fiber or chop) daily in order to help prevent such abnormal behavior. The ground feed is mixed with varying amounts of saliva depending on the duration of the feed intake ( Table 3.4). This means that the DM of the boluses swallowed is higher after feeding concentrates than roughage. The occurrence of esophageal obstructions depends not only on the swelling capacity of the feedstuff (for example, dried sugar beet pulp), but also the speed of the feed intake and the size and DM content of the boluses swallowed. Table 3.4 Principal differences between feeding roughage and concentrate feed Adult horses (500 kg BW) secrete >100 L fluid/day into the pre-cecal gut at approximately 70–100 mL/min. The DM content of the small intestine is about 5% so that even indigestible fibrous particles can be easily passed to the cecum. At the ileocecal junction, the chyme flow is stopped and the contents are discontinuously pressed into the cecum (5–7 times/h; up to 1 L at a time), which means that obstruction is a potential risk. There is a large water and electrolyte turnover in the gastrointestinal tract. While considerable amounts of water, sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl) enter the small intestine via the saliva, stomach juices, pancreatic juice and bile, only about 50% of water, 35% Na and 80% Cl will be absorbed by the end of the ileum. Therefore a large ileocecal flow of water and Na (and to a lesser extent chloride) takes place ( Table 3.5), but most of the water and electrolytes that enter the large intestine will be absorbed. Table 3.5 Guide to the daily intake and turnover of water (L/100 kg BW) and electrolytes (g/100 kg BW) 1 1Based on Meyer, H., Coenen, M. (2002) Pferdefütterung (Horse Nutrition), 4th ed, Blackwell Scientific Publications, London. The large water and electrolyte turnover in the intestine has two consequences: 1. With an ileus (q.v.) in the small intestine, the intestine will fill up very quickly proximal to the blockage. The liquor may possibly reach back to the stomach while the animal becomes dehydrated. 2. Diarrhea (q.v.) in adult horses is mainly related to dysfunction of the large intestine because an elevated flow of water from the small intestine can usually be reabsorbed in an intact functional large intestine. As described above, large amounts of starch and, to a lesser extent, protein, ingested in a single meal may have an effect on digestion both in the stomach and the small intestine. In addition, significant amounts reach the large intestine, stimulating an almost explosive growth of microorganisms. Gas production can exceed the rate at which the methane, hydrogen and carbon dioxide are normally absorbed into the blood and expelled through the lungs so that the lumen of the large intestine becomes distended. Moreover, the rapid production of VFA and lactic acid in particular causes a rapid decrease in pH of the fluid, increases the permeability of the mucosa and upsets the microbial balance. This favors the growth of organisms that can withstand a lower pH, stimulating more lactic acid production and causing the death of certain bacteria that cannot survive under such conditions, thereby releasing endotoxins (non-protein lipopolysaccharide fragments of the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria) and other compounds. These endotoxins, together with the other unwanted compounds produced as a consequence of this change in the conditions of the hindgut, may be absorbed into the blood and have further adverse effects. The blood flow to the feet, for example, may be particularly sensitive to some of these factors that may in turn trigger the development of laminitis (q.v.). 1. The ebb and flow of the microbial population of the hindgut, in numbers of organisms and in their species distribution between meals, is less marked than when starch and protein are the principal substrates. 2. By diluting readily fermentable material, wild fluctuations in the pH of the hindgut are prevented and thus the likelihood of acidosis is reduced. Foals are highly susceptible to ulceration because they start secreting gastrin just after birth before the gastric mucosa has fully developed. In addition, stressful weaning programs may act as an exacerbating factor in the development of gastrointestinal tract ulcers. There is a strong correlation between the diet fed and the pH of the stomach. Concentrate diets have always been implicated but ensuring that these are fed in small amounts, possibly in combination with forages such as alfalfa hay, may help. A high forage intake, which encourages chewing and stimulates salivation, may also be advantageous. Turning out to pasture can be very beneficial for those that are affected. Medical treatment is often required. Imprecision in the assessment of nutrient requirements is compounded by uncertainty in feed analysis. The bioavailability of nutrients also varies between feed sources. The values given in Table 3.6 assume a high bioavailability from the ration. Table 3.6 Guide to the minimum daily nutrient requirements of horses 1 1Based on National Research Council, NRC (1989) Nutrient Requirements of Horses, 5th ed, National Academy Press, Washington DC. 3See also Tables 3.15 and 3.16. 4See also Tables 3.17 and 3.18. This will tend to overestimate the weight, for example, of those horses with reduced gut fill in hard work such as the fit racehorse and is not reliable for the pregnant mare in late gestation or for young, growing animals, etc. The requirements for water are given in Table 3.7. The water content of the body should remain within the approximate limits of 68–72% of fat-free mass. Values below this represent a dehydrated state. Water is lost by excretion in urine, feces and sweat, as well as by evaporation from the lungs and in milk. Lactation can increase needs by 50–70% above maintenance. Table 3.7 Guide to the minimum 1 water needs (kg) of horses per kg of feed DM consumed and the water (kg) provided by pasture herbage per kg herbage DM (1 kg water is equivalent to 1 L) 1Quantities of water given assume ideal environmental conditions. The requirement for supplementary water is influenced both by the amount of DM consumed and by the moisture content of feeds available. Cereals and hay contain approximately 10% moisture whereas pasture herbage contains 40–80% moisture depending on season and rainfall. These sources affect the supplementary amounts of water required ( Tables 3.7 and 3.8). Dry mares (or other non-lactating horses) on lush pastures with shade, undertaking no work, can thrive without additional water, although it is always advisable that a clean supply be made available. Pregnant and lactating mares should be provided with supplementary water at all times (see Tables 3.7 and 3.8). Foals should have adequate access from around 2 weeks of age. The requirements of the breeding stallion are similar to those of the pregnant mare. Table 3.8 Guide to the minimum 1 supplementary water requirements of mares (liters daily per mare)—refer to Table 3.7 for maintenance levels 1These amounts are minimum. They assume ideal conditions and will be insufficient for mares on parched pasture with environmental temperatures >30°C. 2Needs of the breeding stallion are similar to those of the pregnant mare.

Equine nutrition and metabolic diseases

INTRODUCTION

GUIDE TO TYPICAL FEEDSTUFFS

CEREALS, SUGAR BEET AND OIL SEEDS AS FEEDSTUFFS

Major cereals fed to horses

Vegetable oils

FORAGES AND OTHER FIBER SOURCES

Hay

Silage

Hydroponics

METHODS OF FEED PROCESSING

FEEDSTUFFS ANALYSIS

THE DIGESTIVE TRACT

PHYSIOLOGY AND PATHOLOGY OF DIGESTION

Mastication

Roughage

Concentrate feed

Duration of feed intake

Long

Short

Salivation

Heavy

Less intensive

Dry matter of swallowed boluses (%)

<15

>25

Filling of the stomach

Slowly

Quickly

Content of the stomach (temporary)

Moderate

Moderate to high 1

Dry matter of stomach content (%)

20

30–40

pH reduction in region of pylorus

Normal

Retarded

Microbial activity in stomach and small intestine

Moderate

Moderate to high 1

Production of organic acids in the large intestine

Continuously

Discontinuously with the risk of low pH in the cecum

Feces dry matter (%)

20

20–45

Stomach and small intestine

Water and electrolytes

Dysfermentation

The importance of fiber

Gastric ulceration

NUTRIENT REQUIREMENTS

INTRODUCTION

BODY WEIGHT ESTIMATIONS

WATER

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Equine nutrition and metabolic diseases

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue