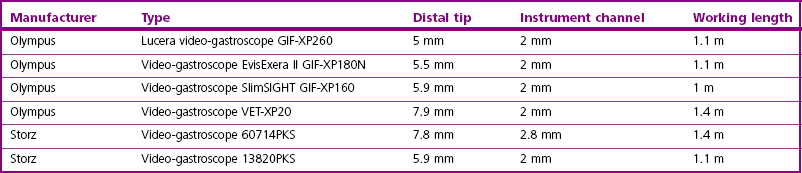

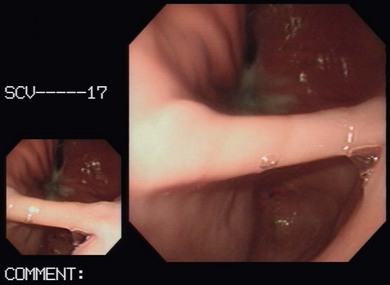

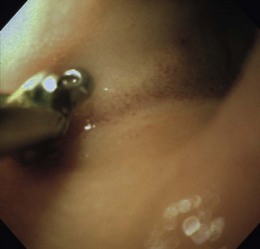

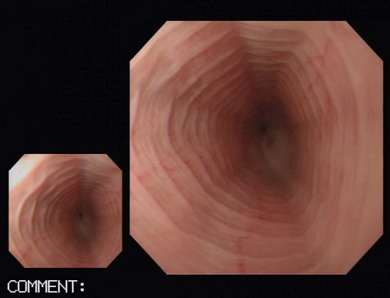

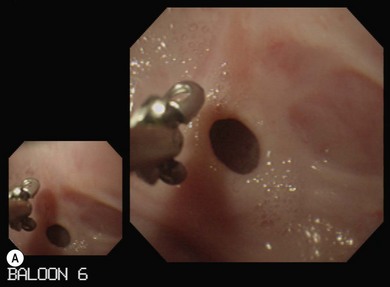

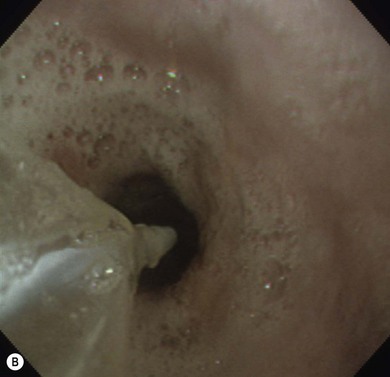

Chapter 9 Gastrointestinal endoscopy can be used for assessment of the stomach, upper small intestine, and the rectum and colon in the cat.1,2 The ability to collect endoscopic biopsies is one of the major advantages and aims of performing gastroendoscopy.3 The larger the biopsy channel, the larger the biopsies that can be collected and therefore the more likely they are to be of diagnostic quality. The compromise is that the larger the distal tip size, the more difficult pyloric intubation will be. The instrument channel should be at least 2 mm in order to be able to obtain diagnostic biopsy samples. There are several scopes on the market that can be considered (Table 9-1). Prior to anesthetizing the patient, ancillary equipment should be prepared (Box 9-1) and endoscopy equipment checked that it is fully functional (including air pump, suction unit and valve, air/water valve, tip deflection, light source image, biopsy forceps, recording equipment). Common reasons for performing upper GI endoscopy in cats are listed in Box 9-2. Pre-medication prior to induction of anesthesia is routine. Atropine is not used routinely, although some advocate that it can make pyloric intubation easier, and it may reduce the risk of vagally induced bradycardia during the procedure. An intravenous catheter should be in place, and fluids administered throughout the procedure. Induction of anesthesia is routine. Nitrous oxide should not be used since insufflation of the stomach permits diffusion of nitrous oxide into it and causes gastric overdistension. Intravenous midazolam or diazepam can be useful if there is difficulty intubating the pylorus, or if the cat becomes uncomfortable (e.g., tachypneic) during this procedure, or if the GIT is particularly inflamed. For further information on anesthesia see Chapter 2.1 The cat should be positioned in left lateral recumbency for routine GI endoscopy (upper and lower), so that the gastric antrum is uppermost, allowing air to fill it and make the pylorus more visible, and that the descending colon lies ventrally, which aids intubation of the transverse and ascending colon (Fig. 9-1). For esophagoscopy where conditions such as mega-esophagus, esophageal strictures or esophageal foreign bodies are suspected, the cat should be kept in sternal recumbency with the head elevated in order to reduce the risk of aspiration. For PEG tube placement, the cat is positioned in right lateral recumbency. The endoscopist should be positioned in such a way that they have a good view of the video monitor, but also in a way that the insertion tube outside of the patient is kept in as straight a line as possible to prevent difficulty steering and advancing, which occurs if there is looping of the insertion tube outside the patient. The quality of the biopsies obtained is determined mainly by the size of the forceps (dependent on the size of the scope), and the pressure exerted on the tissue by the operator. This is a big limitation in feline endoscopy as the patient size limits the size of endoscope, and therefore the size of biopsy forceps that can be used. Therefore, in order to obtain diagnostic quality biopsies, there is no room for poor operator technique. Exerting maximal pressure can be achieved by positioning the biopsy cups perpendicular to the tissue being sampled (Fig. 9-2). Being able to do this effectively and knowing how much pressure can safely be applied comes with experience. Deflating the viscus before biopsy also helps increase the size of the sample by reducing stretching of the mucosa. Figure 9-2 Duodenum from a cat with inflammatory bowel disease, illustrating biopsy technique, positioning the biopsy cups perpendicular to the mucosa. (Courtesy of the University of Bristol.) Delay in intubating the pylorus, combined with insufflation of air, makes pyloric intubation more difficult. Therefore it is usual to only quickly visually inspect the esophagus and stomach on the way down, leaving more complete evaluation to the end of the procedure (except where esophagoscopy is the main purpose of the procedure). The endoscope is inserted through the upper esophageal sphincter by applying only gentle pressure and insufflating small amounts of air. Once through the sphincter the tip should be adjusted so that the esophageal lumen is in the center of the view, and the endoscope gently advanced to the lower esophageal sphincter. A quick inspection of the mucosa on the way down ensures that any pathological lesions can be distinguished from iatrogenic damage when closer inspection is performed on withdrawal. In cats, the distal esophagus has distinct circular folds and the lower esophageal sphincter may be seen as a star or slit-like opening (Fig. 9-3). Figure 9-3 The endoscopic appearance of the normal feline esophagus. (Courtesy of the University of Bristol.) The most common pathologies observed in the feline esophagus are esophagitis, esophageal ulceration, and esophageal strictures (Fig. 9-4A). Biopsies are not routinely taken from the esophagus as the mucosa is very tough. Masses should be biopsied, but these are rare. With esophageal strictures, endoscopy can be used to guide balloon dilation, by passing a balloon catheter alongside the endoscope (Fig. 9-4B). When the stricture is very narrow it can be difficult to insert the balloon into the stricture and great care needs to be taken when directing the balloon to ensure that the tip does not cause further esophageal trauma or esophageal perforation. See Chapter 27 for more information on esophageal disease. Figure 9-4 Esophageal stricture. (A) The endoscopic biopsy forceps (oval fenestrated forceps without a central spike) give an indication of the diameter of the strictured area. (B) A balloon catheter is being advanced through the lumen of the oesophageal stricture to allow balloon dilation. (Courtesy of the University of Bristol.) Once at the lower esophageal sphincter, the endoscope tip should be angled towards it with continued insufflation and gently advanced through into the stomach. As the endoscope enters the stomach the junction of the fundus and body of the stomach can be seen, with parallel rugal folds on the greater curvature running towards the pyloric antrum (Fig. 9-5). This provides an important landmark in locating the pylorus. The other most important landmark is the angularis incisura (angle of the lesser curvature) with the cardia above, and the pyloric antrum below, and this can be located by retroflexing the endoscope tip fully to first locate the cardia (Fig. 9-6) and then slightly reducing the retroflexion to bring the lesser curvature into view. Some insufflation is required to visualize these landmarks, but over inflation will make pyloric intubation difficult, and this is the most common mistake made. In cats, the angle of the lesser curvature is quite acute, and a slide-by technique can be useful for passing the endoscope into the antrum. This involves gently advancing the endoscope along the mucosal surface of the greater curvature; the endoscope tip will be impinging on the gastric mucosa and so red-out will occur, but provided this is moving and the endoscope is not advanced against any resistance, it can continue to be advanced along the greater curvature until the pyloric antrum comes into view. Ensuring that the pylorus is in the center of the screen, and suctioning as the insertion tube is advanced towards it assists with pyloric intubation.

Endoscopy

Gastrointestinal endoscopy

Equipment

Uses and indications

Patient preparation

Endoscopic biopsy technique

Gastrointestinal endoscopy technique

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Endoscopy