CHAPTER 58 Effects of Nutrition on Reproductive Performance of Beef Cattle

“If you feed them, you can breed them. If you don’t, you won’t.”

Bill McDonald, seventh-generation beef producer, Montgomery County, Virginia

The relationship between nutrition and reproduction is bidirectional—that is, reproductive status alters nutrient requirements, but the nutrients assimilated by the cow also alter reproductive function. A beef cow must conceive, carry a fetus to term, give birth, and wean a calf in a 12-month period; thus, she is either pregnant or lactating at any given time. The fetus becomes a high priority for nutrient repartitioning in the dam, which can increase nutrient requirements by 75% at the end of pregnancy to support a weight gain of up to 70 kg for the fetus, the placenta, and fetal fluids.1 Likewise, nutrients are repartitioned again at calving to support lactation, which can increase requirements by 50% to 100% above maintenance.2 Hormonal changes associated with pregnancy and lactation aid in the prioritization of nutrients; however, a negative energy balance during early lactation modifies the signals that initiate ovarian cyclic activity.

NUTRITION AND FEMALE REPRODUCTION

Nutrient Requirements of the Beef Cow

Abnormalities in reproductive function may not be detected by the producer or the veterinarian until weeks or months after the causative insult, which may be infectious, toxic, or nutritional. The nutrient demands of the cow relative to the feed supply available can be evaluated historically or prospectively. The nutritional requirements of beef cows vary with their reproductive status3:

Energy and protein requirements during each of these four periods are listed in Table 58-1.

Table 58-1 Protein and Energy Requirements for an 1100-lb Beef Cow during the Reproductive Cycle

| Reproductive Period | Net Energy (Mcal/day) | Protein (kg/day) |

|---|---|---|

| Calving to conception (85 days) | 14.9 | 1.05 |

| Conception to weaning (125 days) | 12.2 | 0.86 |

| Weaning to late gestation (110 days) | 9.2 | 0.64 |

| Late gestation (50 days) | 10.3 | 0.73 |

Data from Corah LR: Nutrition of beef cows for optimizing reproductive efficiency. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 1988;10:659; and Corah LR: Body condition: an indicator of the nutritional status. Agric Pract 1989;10:25.

Abnormalities in Female Reproduction

Veterinarians or producers commonly recognize reproductive abnormalities when cows do not calve or when a large percentage of cows are found to be open when examined for pregnancy. The nutritional events that result in failure of cows to become pregnant may have occurred 4 to 18 months previously. Although overlap among diagnostic groups will be inevitable, the practitioner can attempt to categorize the nonpregnant cows as those that failed to have normal estrous cycles, those that failed to conceive, or those that conceived but did not remain pregnant; each category suggests different causes. A thorough review of the diagnosis of nutritional infertility has been published.4

Failure to Cycle: Heifers

Most production systems require that heifers calve at 23 to 24 months of age. Heifers that calve early in the calving season wean more and heavier calves during their lives.5 Heifers, therefore, should reach puberty at 12 to 13 months of age to allow one or two estrous cycles before breeding at 14 months. Age at puberty is influenced by breed, by season, and by plane of nutrition.5,6 Growth rates during the preweaning and postweaning periods are inversely related to age at puberty, and the postweaning growth rate is associated with plane of nutrition.5 The onset of puberty appears to be associated with increased frequency of luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion. Increased pulsatile LH secretion is associated with increased energy intake, whereas reduced energy intake suppresses LH secretion in heifers.7 Delayed puberty also is associated with low concentrations of insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I). Proliferation of steroidogenic capacity of thecal8 and or granulosa cells9 is associated with decreased concentration of IGF-I. Recent research has focused on leptin as a regulator for reproductive function and particularly as a mediator for nutritional cues. Short-term fasting of peripubertal heifers decreased leptin gene expression, and circulating leptin concentrations were coincident with reductions in circulating concentrations of insulin and IGF-I and in LH pulse frequency, resulting in delayed puberty.10 Conversely, serum leptin concentration was positively correlated with changes in increasing body weight in prepubertal heifers.11 Addition of ionophores to the ration increases growth rate but also tends to decrease age at onset of puberty, independent of weight.12,13

Historical recommendations have been that heifers should be fed to reach a target weight of 65% to 70% of their mature weight at breeding. Brahma-cross heifers fed to a target weight of 318 kg showed estrus earlier and had increased rates of pregnancy after 20 days of breeding (39% versus 9%) and at the end of the breeding season (82% versus 66%) compared with heifers fed to a target weight of 272 kg.14 Conversely, spring-born, weaned beef heifers (213 kg) were fed over winter to achieve either 55% or 60% of mature weight at breeding. Heifers fed for 60% mature weight were heavier at breeding (313 versus 289 kg) and had increased condition scores (6.0 versus 5.6), and more were cycling before the breeding season (85% versus 74%). Pregnancy rates at the end of the 45-day breeding season, however, were similar between groups (88% versus 92%) The heifers were then followed through three calvings; production did not differ between groups except for higher 205-day adjusted weaning weights after the second calving for the heifers fed to achieve 55% of mature weight at breeding.15

Decreased Reproductive Rates in Mature Cows

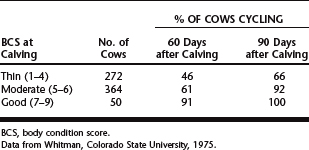

Breed, suckling stimulus, and plane of nutrition affect return to estrus in postpartum cows.16 Body condition score (BCS) at calving and nutrient supply during the early postpartum period affect the return of ovarian cyclic activity and subsequent pregnancy rates (Table 58-2).

Alterations in plane of nutrition and BCS alter hormonal status. For example, pulse frequency of LH was increased 3 weeks post partum in cows that calved in moderate body condition compared with cows that calved in poor body condition.17 Postpartum LH secretion is less responsive to dietary protein. LH release at 20, 40, and 60 days after calving did not differ between cows fed adequate crude protein before calving (0.96 kg/day) and cows fed restricted crude protein (0.32 kg/day) starting at 90, 60, and 30 days before calving.18

Several studies have shown that body condition at calving alters the time between calving and conception and pregnancy rates. Pregnancy rates for cows with BCS of 4 and 5 at calving were lower than pregnancy rates for cows with BCS of 6 and 7 at calving (64.9% and 71.4% versus 87.0% and 90.7%, respectively).19 In a similar study, cows with BCS of 4 at calving had a pregnancy rate of 50%, whereas cows that calved with BCS of 5, 6, and 7 had pregnancy rates of 81%, 88%, and 90%, respectively.20 BCS at calving also affects calving interval. Cows with BCS greater than 5 had 10 to 18 fewer days open than cows with BCS of 4.19 Investigators using a 5-point condition score scale demonstrated a decrease in calving interval of 11.2 days for each unit increase in body condition at calving.21 This is approximately equivalent to a change of 5 to 6 days in calving interval for a unit change in condition score when a 9-point scale is used. Cows with BCS greater than 5 displayed estrus 12 days earlier after calving and had 14 fewer days open than cows calving with BCS less than 4.18 A cubic relationship between condition score at calving and pregnancy rate has been described: The effect of a 1-unit change in BCS on pregnancy rate was found to be greater for cows with BCS between 4 and 6 than for fatter or thinner cows.23

One study demonstrated that BCS at the beginning of the breeding season influenced pregnancy rate and calving interval; however, changes in live weight from calving to the beginning of the breeding season and BCS at the end of the breeding season had no effect on reproductive performance.21 Changes in postpartum nutrient intake may benefit thin (BCS <4) more than adequately nourished cows. Pregnancy rates were evaluated in cows whose calves were removed for 48 hours at initiation of breeding. Cows with BCS less than 4 at calving that were fed to lose weight after calving had decreased pregnancy rates at 40 and 60 days after breeding compared with cows fed to gain weight after calving, cows fed to maintain their weight after calving, or cows fed to lose weight but with 2 weeks of increased energy intake before breeding (flushing). The ration fed after calving did not alter the pregnancy rate in cows that calved with BCS greater than 5.22 Conversely, cows fed to gain 0.9 kg/day after calving had higher first-estrus pregnancy rates and higher serum IGF-I, leptin, and glucose concentrations post partum than cows fed to gain 0.5 kg/day. Condition score at calving (group means 4.4 versus 5.1) did not influence hormonal status after calving.24

The timing of the calving season may modify the influence of nutrition on reproductive performance. BCS at calving may be more critical in spring-calving herds, whereas changes in BCS from calving to breeding may be more important in fall-calving cows owing to differences in availability of feed.25

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree