16 Disorders of the Uterus

This is a good question because pregnancy and pyometra happen at the same time in the cycle. Pregnant dogs sometimes become inappetent at about the third week of gestation but they should not have a fever and should not have vulvar discharge. Bitches with pyometra generally either have creamy, foul-smelling vulvar discharge (open-cervix pyometra) or have fever, lethargy, abdominal distension, and occasionally vomiting and increased thirst and urination. If you’re unsure and if the bitch is at least 24 days from having been bred, ultrasound can be used to differentiate pyometra from pregnancy.

II. SUBINVOLUTION OF PLACENTAL SITES

Subinvolution of placental sites (SIPS) is, as the name implies, delayed healing of the sites on the uterine lining from which placentas pulled away. This disorder also occurs postpartum (see Chapter 14).

IV. CYSTIC ENDOMETRIAL HYPERPLASIA/PYOMETRA

A. DEVELOPMENT

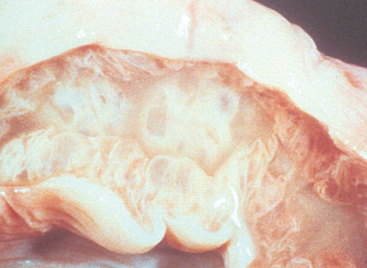

As the name implies, CEH is a cystic thickening of the endometrium, or uterine lining (Figure 16-1). CEH can be created experimentally by exposing uterine tissue either to estrogen or to progesterone. CEH develops to a greater extent and more quickly if the uterus is first exposed to estrogen and then is exposed to progesterone. This is the normal hormonal sequence of the estrous cycle in dogs. CEH develops over time after repeated estrous cycles in the dog. There are four grades of CEH described by Dow: worsening in severity from type I (mild changes) to type IV (severe changes with associated inflammation and tissue destruction). As might be expected because this is a progressive disorder, mean age at diagnosis of dogs with type I CEH is younger than is mean age of dogs diagnosed with type IV CEH. By the age of 9 years, two thirds of intact bitches had some degree of CEH in one study.

Bitches with a history of receiving estrogen or progesterone as therapy for pregnancy termination or estrus suppression are more likely to develop CEH, although CEH and subsequent pyometra are not more common in bitches with a history of false pregnancy (see Chapter 18). Dogs with CEH-pyometra do not produce higher concentrations of progesterone during diestrus, nor do they produce progesterone longer during diestrus.

The second step in the development of pyometra is infection. During proestrus and estrus, the cervix is open. This allows the normal bacterial flora of the vagina to ascend into the uterus, which occurs during every estrous cycle in bitches whether or not they are bred. In bitches with a normal uterus, bacteria are expelled from the uterus before the onset of diestrus. In bitches with CEH, bacteria colonize the thickened uterine lining and are not expelled. As diestrus begins, the cervix is closed, preventing expulsion of bacteria. Under the influence of progesterone, the uterus does not contract and the uterine glands are stimulated to produce secretions. This promotes rapid growth of the bacteria embedded in the uterine lining.

Organisms that cause pyometra are those of the normal vaginal flora. The vagina is not sterile at any time, and a large number of organisms live in balance in the uterus (Table 16-1). The most common organism associated with pyometra is Escherichia coli. It has been demonstrated that the organism causing infection in a given bitch is the same subtype of organism found in the bitch’s feces and on her skin. Dogs that develop pyometra do not do so after contracting infection from a male to which they were bred or after being exposed to a new environment or new bitch or stud dog in the kennel but instead are infected with their “own” bacteria.

Table 16-1 Organisms Cultured from the Vagina of Normal Intact or Spayed Dog Compared with Organisms Cultured from Bitches with Pyometra*

| Organisms from the Normal Vagina | Organisms from Bitches with Pyometra |

|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Escherichia coli |

| Streptococcus spp. | Streptococcus spp. |

| Pasteurella spp. | Staphylococcus spp. |

| Staphylococcus spp. | Klebsiella spp. |

| Bacillus spp. | Proteus spp. |

| Enterococcus spp. | Pseudomonas spp. |

| Proteus spp. | Corynebacterium pyogenes |

| Klebsiella spp. | Enterococcus spp. |

| Haemophilus spp. | Pasteurella spp. |

| Moraxella spp. | Serratia spp. |

| Flavobacterium | Haemophilus spp. |

| Pseudomonas spp. | Bacillus spp. |

| Corynebacterium spp. |

* Listed from greatest to least prevalence.

When infection develops in the uterus, discharge and white blood cells fill the uterine lumen. The bacteria float in a sea of pus within the center of the uterus, making it difficult to reach them with antibiotics, which do not diffuse into that fluid. Bacteria also may form a biofilm, a structure of proteins and sugars that supports the bacteria and prevents ready eradication. The cervix may or may not open because of the pressure of fluid against the cervix as the uterus distends.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree