Chapter 31 Diseases of the Thyroid Gland

HYPOTHYROIDISM IN DOGS

Etiology

Secondary (Pituitary) Hypothyroidism

• Cystic Rathke pouch: This form occurs in German shepherd pituitary dwarfs and is associated with concurrent hormone deficiencies including growth hormone deficiency, hypoadrenocorticism, and hypogonadism (see also Chapter 36).

Clinical Signs

The clinical signs of hypothyroidism are insidious in onset because of the gradual destruction of the thyroid gland. Signs are diverse and range from mild to severe (Table 31-1).

Table 31-1 CLINICAL SIGNS AND LABORATORY FINDINGS IN DOGS WITH HYPOTHYROIDISM

| Common Findings | Uncommon Findings | |

|---|---|---|

| Dermatologic Abnormalities | Neuropathy | |

| Seborrhea | Vestibular | |

| Alopecia | Facial | |

| Pyoderma | Generalized | |

| Myxedema | Laryngeal paralysis | |

| Obesity | Myopathy | |

| Lethargy | Megaesophagus | |

| Weakness/exercise intolerance | Central nervous system abnormalities | |

| Low-voltage ECG complexes | Dwarfism | |

| Bradycardia | Reproductive abnormalities (anestrus) | |

| Hypercholesterolemia | Insulin-resistant diabetes mellitus | |

| Nonregenerative anemia | Ocular abnormalities | |

| Myxedema stupor or coma | ||

ECG, electrocardiographic.

Integument

• Myxedema: Thickening of the skin, especially facial, secondary to glycosaminoglycan accumulation, leading to a “tragic” facial expression.

Nervous System and Muscle

• Megaesophagus is very rare and may occur secondary to myopathy, neuropathy, or concurrent myasthenia gravis.

Congenital Hypothyroidism

• Disproportionate dwarfism, broad skull, macroglossia, delayed dental eruption, hypothermia, distended abdomen, retention of puppy haircoat, dry skin, and gait abnormalities.

Diagnosis

Basal Total Thyroid Hormone Concentration (T4 and T3)

• Serum triiodothyronine (T3) concentration is unreliable in the diagnosis of hypothyroidism since it is often within the reference range in hypothyroid dogs.

• Breed differences result in low serum T4 in greyhounds, deerhounds, Alaskan sled dogs, and probably other breeds.

• Non-thyroidal illness (e.g., hyperadrenocorticism, renal disease, or neoplasia) causes a decrease in total T4 and T3.

• Administration of various drugs, including glucocorticoids, sulfonamides, anticonvulsants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and radiocontrast agents, lowers serum T4 and T3.

Free Thyroxine Concentration

• Free T4 is the portion of T4 that is not bound to plasma carrier proteins (normally 0.1% of total T4).

• Equilibrium dialysis is the only reliable method for measurement of free T4 in dogs with non-thyroidal illness. Free T4 by equilibrium dialysis is the most accurate single test for diagnosing hypothyroidism (see the Endocrine Diagnostic Laboratory of the Michigan State University website: www.ahdl.msu.edu).

Serum Endogenous Canine Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone Concentration

• Serum TSH concentration is increased in most cases of primary hypothyroidism due to loss of negative feedback of T4 and T3 on the pituitary gland.

Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone Stimulation Test

• The most reliable method of confirming the diagnosis of hypothyroidism in dogs is by demonstrating a low resting T4 that fails to increase following TSH administration.

• Test protocol: Collect blood for measurement of serum T4 before and 4 hours after IV administration of 100 μg human recombinant TSH.

Antithyroglobulin Antibodies

• Antithyroglobulin antibodies can be present in euthyroid dogs, and they do not indicate hypothyroidism.

Treatment

Synthetic L-Thyroxine

• The initial dosage of L-T4 is 0.022 mg/kg q12h PO. Once-daily treatment at the same dose is usually adequate for resolution of clinical signs and can be used initially or after twice-daily treatment has resulted in a good clinical response.

• Reevaluate after 6 to 8 weeks of treatment by examining for resolution of clinical signs and measuring serum T4.

• A serum T4 concentration collected 4 to 6 hours after pill administration should be near the upper limit or slightly above the reference range; T3 concentration may be low despite normal or high T4.

• If signs of hyperthyroidism occur, such as polyuria, polydipsia, tachycardia, weight loss, diarrhea, or tachycardia, measure serum T4 and T3, stop treatment for 1 to 2 days, and reduce the dosage based on this evaluation.

HYPOTHYROIDISM IN CATS

Etiology

• Congenital hypothyroidism is associated with thyroid gland atrophy or defective thyroid hormone biosynthesis. In many kittens, this may go undetected and may result in early death.

Diagnosis

• Confirmed by finding subnormal resting serum T4 concentration that fails to increase 4 to 6 hours after IV administration of TSH (see “Hypothyroidism in Dogs”).

• Can also be confirmed by finding low serum concentrations of total T4 and free T4 (see “Hypothyroidism in Dogs”).

HYPERTHYROIDISM IN CATS

Etiology

Adenomatous Hyperplasia

• In cats, the disease most closely resembles toxic nodular goiter in human patients, which is caused by hyperfunctioning adenomatous thyroid nodules.

Clinical Signs

All of the clinical manifestations of hyperthyroidism are due to the effects of excessive thyroid hormone. These effects are generally stimulatory. They cause increased heat production and heightened protein, carbohydrate, and lipid metabolism in virtually all body systems and tissues. Clinical signs can range from mild to severe (Table 31-2).

Table 31-2 FREQUENCY OF HISTORICAL AND CLINICAL SIGNS IN CATS WITH HYPERTHYROIDISM

| Clinical Finding | Percentage of Cats |

|---|---|

| Weight loss | 95–98 |

| Hyperactivity/difficult to examine | 70–80 |

| Polyphagia | 65–75 |

| Tachycardia | 55–65 |

| Polyuria/polydipsia | 45–55 |

| Cardiac murmur | 20–55 |

| Vomiting | 33–50 |

| Diarrhea | 30–45 |

| Increased fecal volume | 10–30 |

| Decreased appetite | 20–30 |

| Lethargy | 15–25 |

| Polypnea (panting) | 15–30 |

| Muscle weakness | 15–20 |

| Muscle tremor | 15–30 |

| Congestive heart failure | 10–15 |

| Dyspnea | 10–15 |

General Appearance and Behavior

• Impaired stress tolerance. The hyperthyroid cat is prone to respiratory distress and weakness when stressed. Cardiac arrhythmias or arrest can occur in extreme cases.

Thyroid Gland

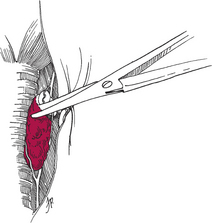

• Enlargement of one or both lobes of the thyroid gland is palpable in >90% of cats with hyperthyroidism. To palpate the thyroid gland, extend the cat’s neck and tilt the head back slightly. Using the thumb and forefinger, gently palpate the tissues on either side of the trachea, starting at the larynx and moving caudally to the thoracic inlet (see Fig. 1-3 in Chapter 1).

Gastrointestinal System

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree