Chapter 69 Diseases of the Intestines

DIARRHEA

Acute versus Chronic Diarrhea

Acute Diarrhea

Chronic Diarrhea

Small Bowel versus Large Bowel

The anatomic localization of the disease process to the small or large bowel is based on the patient’s defecation pattern and fecal characteristics (frequency, volume, consistency, color, odor, composition) (Table 69-1). This distinction is most useful in dogs for determining the direction of subsequent diagnostic evaluations. Diffuse diseases of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract may produce concurrent small and large bowel signs and, sometimes, gastric signs such as vomiting.

Table 69-1 SMALL BOWEL VERSUS LARGE BOWEL DIARRHEA

| Observation | Small Intestine | Large Intestine |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency of defecation | Normal to slightly increased | Very increased |

| Fecal output | Large volumes | Small volumes frequently |

| Urgency or tenesmus | Absent | Present |

| Dyschezia | Absent | Present with rectal disease |

| Mucus in feces | Absent | Present |

| Exudate (WBC) in feces | Absent | Present sometimes |

| Hematochezia (red blood) | Rare | Frequent |

| Melena (digested blood) | Present sometimes | Absent |

| Steatorrhea | Present sometimes | Absent |

| Flatulence and borborygmus | Present sometimes | Absent |

| Weight loss | Present sometimes | Rare |

| Vomiting | Present sometimes in dogs; frequent in cats | Occasional |

WBC, white blood cells.

Small Bowel Diarrhea

Chronic small bowel diarrhea can be associated with maldigestion and malabsorption and is characterized by a high volume without urgency, tenesmus, or marked increase in frequency. Weight loss and decline in body condition (malnutrition) may occur.

Large Bowel Diarrhea

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH FOR DIARRHEA

Physical Examination

A complete physical examination may reveal important clues about the severity, nature, and cause of diarrhea (Table 69-2), although in many patients the findings are nonspecific.

Table 69-2 PHYSICAL FINDINGS IN INTESTINAL DISEASE

| Physical Finding | Potential Clinical Associations |

|---|---|

| General Physical Examination | |

| Dehydration | Diarrheal fluid loss |

| Depression/weakness | Electrolyte imbalance, severe debilitation |

| Emaciation/malnutrition | Chronic malabsorption, protein-losing enteropathy |

| Dull unthrifty haircoat | Malabsorption of fatty acids, protein, and vitamins |

| Fever | Infection, transmural inflammation, neoplasia |

| Edema, ascites, pleural effusion | Protein-losing enteropathy |

| Pallor (anemia) | Gastrointestinal blood loss, anemia of chronic inflammation |

| Intestinal Palpation | |

| Masses | Foreign body, neoplasia, granuloma |

| Thickened loops | Infiltration (inflammation, lymphoma) |

| “Sausage loop” | Intussusception |

| Aggregated loops | Linear intestinal foreign body, peritoneal adhesions |

| Pain | Inflammation, obstruction, ischemia, peritonitis |

| Gas or fluid distention | Obstruction, ileus, diarrhea |

| Mesenteric lymphadenopathy | Inflammation, infection, neoplasia |

| Rectal Palpation | |

| Masses | Polyp, granuloma, neoplasia |

| Circumferential narrowing | Stricture, spasm, neoplasia |

| Coarse mucosal texture | Colitis, neoplasia |

Routine Laboratory Tests

Table 69-3 LABORATORY FINDINGS IN INTESTINAL DISEASE

| Abnormal Laboratory Findings | Clinical Associations |

|---|---|

| Hematologic Findings | |

| Eosinophilia | Parasitism, eosinophilic enteritis, hypoadrenocorticism, mast cell tumor |

| Neutrophilia | Bowel inflammation, necrosis, or neoplasia |

| Neutropenia or “toxic” neutrophils | Parvovirus, FeLV, FIV, endotoxemia, or overwhelming sepsis (e.g., leakage peritonitis) |

| Monocytosis | Chronic or granulomatous inflammation (e.g., mycosis) |

| Lymphopenia | Loss of lymphocytes associated with intestinal lymphangiectasia |

| Anemia | GI blood loss, depressed erythropoiesis (chronic inflammation, neoplasia, malnutrition) |

| Elevated PCV | Hemoconcentration from GI fluid loss |

| RBC microcytosis | Iron deficiency (chronic GI blood loss), portosystemic shunt |

| RBC macrocytosis | RBC regeneration, feline hyperthyroidism, FeLV, nutritional deficiencies (rare) |

| Serum Biochemical Findings | |

| Panhypoproteinemia | Protein-losing enteropathy |

| Hyperglobulinemia | Chronic immune stimulation, basenji enteropathy |

| Azotemia | Dehydration (prerenal), primary renal failure |

| Hypokalemia | GI loss of fluid and electrolytes, anorexia |

| Hyperkalemia/hyponatremia | Hypoadrenocorticism, trichuriasis (rare) |

| Hypocalcemia | Hypoalbuminemia, lymphangiectasia, pancreatitis |

| Hypocholesterolemia | Lymphangiectasia, liver disease |

| Elevated liver enzymes or bile acids | Liver disease |

| Elevated amylase/lipase | Pancreatitis, enteritis, or azotemia |

| Elevated thyroxine (T4) | Feline hyperthyroidism |

FeLV, feline leukemia virus; FIV, feline immunodeficiency virus; GI, gastrointestinal; PCV, packed cell volume; RBC, red blood cell.

Fecal Examinations

Table 69-4 DIAGNOSIS OF INTESTINAL PATHOGENS OF DOGS AND CATS

| Pathogen | Method of Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Helminths | |

| Ascarids (Toxocara, Toxascaris leonina) | Routine fecal flotation for ova |

| Hookworms (Ancylostoma) | Routine fecal flotation for ova |

| Whipworms (Trichuris vulpis) | Routine fecal flotation for ova; fenbendazole trial |

| Tapeworms (Taenia, Dipylidium caninum) | Fecal proglottids or flotation for ova |

| Strongyloides | Fecal sediment or Baermann test for larvae |

| Others (flukes) | Fecal zinc sulfate centrifugation-flotation for ova |

| Protozoa | |

| Coccidia (Isospora) | Fecal flotation for oocysts |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | Microplate ELISA, direct immunofluorescence, PCR, Sheather’s flotation |

| Giardia | Fecal zinc sulfate centrifugation-flotation for cysts; fecal ELISA or IFA; duodenal wash for trophozoites; fenbendazole trial |

| Tritrichomonas foetus | Fecal wet smear for trophozoites; InPouch TF culture; PCR |

| Entamoeba histolytica | Fecal wet smear for trophozoites |

| Balantidium coli | Fecal wet smear for trophozoites |

| Viruses | |

| Canine parvovirus | Fecal ELISA (SNAP-Parvo Test) for viral antigen (see Chapter 14) |

| Feline panleukopenia virus | Signs, leucopenia (see Chapter 14) |

| Canine coronavirus | Fecal EM, virus culture, PCR (see Chapter 14) |

| Feline enteric coronavirus and FIP | Signs, serology, fecal EM, PCR, biopsies (see Chapter 10) |

| Rotaviruses | Fecal EM, virus culture, PCR (see Chapter 14) |

| Astrovirus | Fecal EM, PCR (see Chapter 14) |

| Canine distemper virus | Signs (see Chapter 13) |

| Retroviruses (FeLV, FIV) | FeLV antigen test (ELISA, IFA); FIV antibody test (see Chapters 8, 9) |

| Rickettsia | |

| Salmon poisoning (Neorickettsia helminthoeca) | Operculated trematode eggs in feces; rickettsia in lymph node cytology (see Chapter 17) |

| Bacteria | |

| Salmonella | Fecal culture |

| Campylobacter jejuni | Fecal microscopy and culture |

| Yersinia enterocolitica, Y. pseudotuberculosis | Fecal culture |

| Bacillus piliformis (Tyzzer’s disease) | Biopsy (gut, liver) for filamentous bacteria; mouse inoculation |

| Mycobacterium spp. | Acid-fast bacteria in cytology/biopsy; culture, PCR (see Chapter 19) |

| Clostridium perfringens, C. difficile | ELISA-based fecal enterotoxin assays; PCR |

| Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (?) | Fecal culture and toxin assays |

| Fungi | |

| Histoplasma capsulatum | Fungi in biopsies/cytologies; serology (see Chapter 20) |

| Pythium, Zygomycetes | Pythium ELISA; poorly septate hyphae in biopsies (Chapters 20, 40) |

| Others (Candida albicans, Aspergillus, etc.) | Yeast or hyphae in biopsies; fungal culture (see Chapters 20, 40) |

| Algae (Prototheca) | Unicellular algae in cytology or biopsy; fecal culture (Sabouraud’s) |

ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; EM, electron microscopy; FeLV, feline leukemia virus; FIP, feline infectious peritonitis; FIV, feline immunodefi-ciency virus; IFA, immunofluorescent antibody; PCR, polymerase chain reaction test; Rx, therapeutic response.

Fecal Examination for Parasites

Fecal Examination for Infectious Agents

Viruses

Viral diarrhea is generally acute and is confirmed by detection of viral antigen in the feces (ELISA, PCR, etc.) or virus particles by electron microscopy (see Chapter 14).

Bacteria

The common enteropathogenic bacteria in dogs and cats are listed in Table 69-4.

Fungi and Prototheca

The diagnosis of fungal (Histoplasma, Aspergillus, Pythium, Candida) and protothecal infections is usually based on identification of the organisms in feces or more often in rectal scrapings (Histoplasma), tissue aspirates, or intestinal biopsies (see Chapters 20 and 40).

Fecal Examination Using Special Stains

Sudan and Iodine Stain

Fecal staining with Sudan for undigested fat and Lugol iodine for undigested starch may suggest exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (maldigestion); however, these evaluations are too insensitive, nonspecific, and diet dependent to be recommended. These procedures have been replaced by more reliable diagnostic tests for exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (see Chapter 73).

Tests for Fecal Occult Blood

Fecal Proteolytic Activity

Fecal proteolytic activity can be assayed as an indicator of pancreatic secretion of proteases (trypsin) for the diagnosis of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI). The serum trypsin-like immunoreactivity (TLI) assay is more accurate and is now preferred for the diagnosis of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in both dogs and cats (see Chapter 73).

Enteropancreatic Function Tests

The following tests are designed to evaluate digestive and absorptive functions.

Tests for Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency

Tests for exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (pancreatic maldigestion), such as serum trypsin-like immunoreactivity and fecal assays for proteolytic activity, are described in Chapter 73.

Serum Folate and Cobalamin Assays

Serum Folate

Serum Cobalamin

Five-Sugar Absorption Tests for Intestinal Permeability

These oral sugar absorption tests are variations on the other carbohydrate absorption tests. A mixture of sugars is used as a noninvasive molecular probe of mucosal permeability and injury based on urine recovery (in a 6-hour urine sample) after oral administration. These sugar probes measure passive diffusion. Lactulose, cellobiose, and raffinose are probes of the large pores of the paracellular pathway, and urine recovery increases with mucosal epithelial damage. Mannitol and rhamnose are probes of the numerous small pores of the transcellular pathway, and urine recovery decreases with loss of mucosal absorptive surface area (such as villous atrophy). An increase in the lactulose-to-rhamnose ratio is typical of intestinal disease with mucosal damage and increased permeability.

Tests for Protein-Losing Enteropathy

Tests for Bacterial Overgrowth

Radiography and Ultrasonography

Gastrointestinal Barium Contrast Radiography

Upper GI barium radiography is indicated when other evaluations fail to determine the cause of small bowel diarrhea or when intestinal obstruction is suspected (see Chapter 4). This may help detect obstructive lesions, neoplastic masses, and inflammatory lesions that cause an irregular mucosal pattern or distortion of the bowel wall. In most cases, however, diarrhea involves microscopic and functional changes in the bowel that are not detected by barium radiography.

Barium Enema Contrast Radiography

Barium enema radiography is indicated in selected cases of large bowel diarrhea for evaluating the colon and cecum for intussusceptions, neoplasms, polyps, strictures, inflammatory lesions, and colonic displacement or malformation. Colonoscopy is generally preferred over barium enema for evaluating the colon because it yields more definitive diagnostic information.

Abdominal Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is indicated for assessing intestinal wall thickness and layering, for defining intestinal and other abdominal masses, and for evaluating other abdominal organs—e.g., lymph nodes, spleen, pancreas, liver, biliary tract, kidneys, adrenals, and prostate (see Chapter 4).

Endoscopy

Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Duodenoscopy with a flexible fiberoptic endoscope can be performed in the anesthetized animal for visual examination of the upper GI tract, including duodenum; for duodenal aspiration (for quantitative bacterial culture or detection of Giardia trophozoites); and for directed forceps biopsy of the intestinal mucosa (see Chapter 67 for a description of endoscopic equipment and discussion of gastroscopy).

Colonoscopy

Intestinal Biopsy

The least invasive and, in many cases, preferred method for procurement of intestinal biopsies is endoscopy. If endoscopy is not available, or if endoscopic biopsies are inconclusive, consider full-thickness intestinal biopsy by laparotomy (see Chapter 70).

NONSPECIFIC TREATMENT OF DIARRHEA

Dietary, supportive, and symptomatic therapy often is beneficial in diarrhea, especially acute diarrhea. In severe acute diarrhea, fluid and electrolyte therapy can be lifesaving.

Dietary Management

Acute Diarrhea

Fluid Therapy

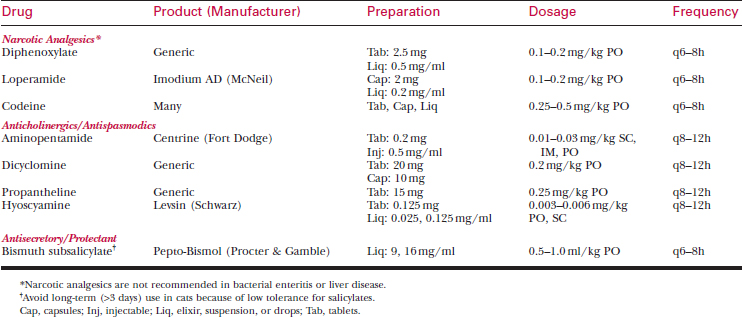

Antidiarrheal Drugs

Opiate and Opioid Narcotic Analgesics

Opioid drugs such as loperamide are the most effective all-purpose antidiarrheal agents (see Table 69-5).

Anticholinergic Drugs

Protectants and Adsorbents

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

Antibiotic Therapy

Cobalamin Therapy

Cobalamin (vitamin B12) is vital for many cellular processes, and it is frequently depleted in patients with chronic small intestinal disease or exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Cobalamin deficiency can impair intestinal mucosal regeneration and cause villous atrophy and malabsorption, exacerbating diarrhea and contributing to anorexia and depression in patients with chronic GI disease.

DIETARY DIARRHEA

Etiology

Diagnosis

DRUG- AND TOXIN-INDUCED DIARRHEA

Etiology

Treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree