Chapter 126 Diseases of the Brain and Cranial Nerves

The brain may be anatomically and functionally divided into three major compartments, the brain stem, cerebellum, and cerebrum. Cranial nerves have their cell bodies within the brain, but most of their nerve fibers course outside the brain. Diseases of the brain and cranial nerves may be neoplastic, infectious, idiopathic, vascular, traumatic, metabolic, toxic, congenital, or degenerative in origin. These disorders may result in dysfunction of a focal, regionally specific brain area or may produce more diffuse or multifocal deficits. Because many different diseases can affect similar areas causing very similar clinical signs, the first portion of this chapter discusses clinical signs of lesions in each brain region. The remainder of the chapter discusses important brain diseases within each etiologic category. Diagnosis of neurologic disease is discussed in Chapter 125, and management of seizures is discussed in Chapter 127.

CLINICAL SIGNS AND NEUROLOCALIZATION

Brain Stem Lesions

Cerebellar Lesions

Forebrain Lesions

Herniation from Space-Occupying Brain Lesions

NEOPLASIA

Etiology

Primary Brain Tumors in the Canine

Primary tumors of the canine brain arise spontaneously and may grow slowly or rapidly.

Clinical Signs

Diagnosis

Laboratory Testing

Electrodiagnostic Testing

Radiography

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Cerebrospinal Fluid Analysis

For CSF tap technique and normal values, see Chapter 125.

Treatment

Corticosteroids

Hyperosmotic Solutions and Diuretics

Anticonvulsant Therapy

Phenobarbital at a dosage of 2.2 to 2.5 mg/kg PO every 12 hours is indicated if seizures are part of the clinical picture (see Chapter 127). Potassium bromide is often required as an additional anticonvulsant if seizures are recurrent.

Specific Chemotherapy

Surgery

Radiation Therapy

Stereotactic Radiosurgery

INFLAMMATORY BRAIN DISEASES

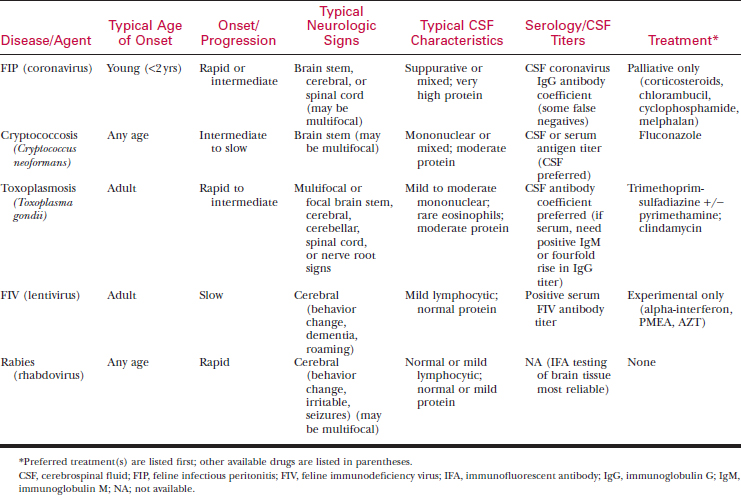

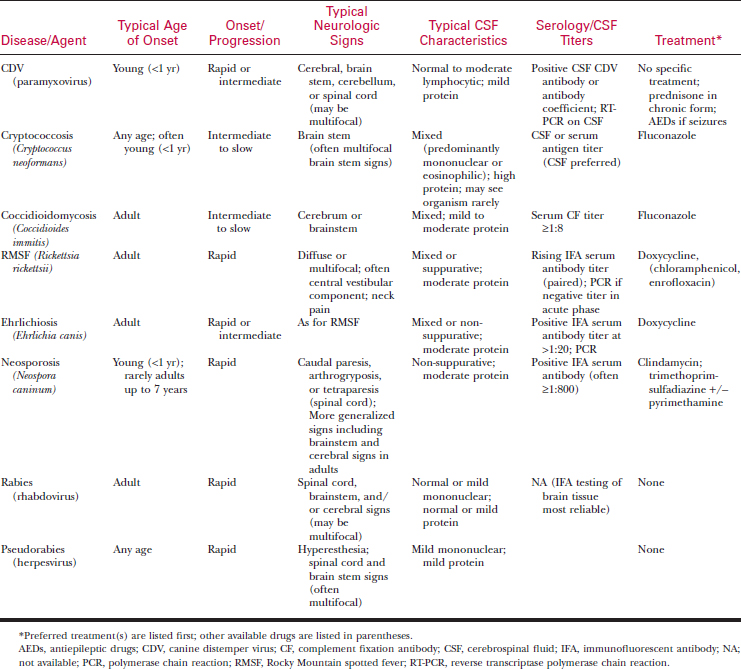

Infectious Meningoencephalitis

Etiology

Diagnosis

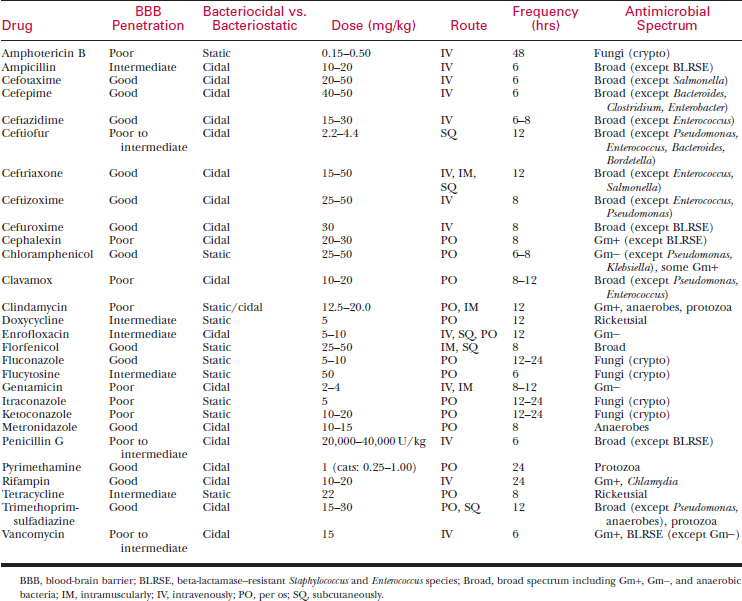

Treatment

IDIOPATHIC INFLAMMATORY BRAIN DISORDERS

Granulomatous Meningoencephalomyelitis

Clinical Signs

Diagnosis

Treatment

Necrotizing Encephalitis

Clinical Signs

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree