Chapter 159 Diagnostic Imaging in Respiratory Disease

RADIOGRAPHIC ANATOMY

• Radiographic evaluation of the nasal cavity and nasopharynx is best accomplished with the patient under general anesthesia. The open-mouth, ventrodorsal view of the maxilla is the best view for assessing disease within the nasal passages. Mirror image symmetry between the right and left nasal passages, on either side of the nasal septum, should be observed. Nasal turbinates appear as thin, lacy mineralized structures surrounded by air. Occasionally, deviation of the nasal septum is seen as a variation of normal. The frontal sinuses are typically underdeveloped in dogs with congenital hydrocephalus or with a domed cranium conformation (e.g., Chihuahua).

• Radiographic evaluation of the upper airways, to include the nasopharynx, oropharynx, larynx and trachea, is best accomplished with the patient in lateral recumbency. The soft palate and epiglottis are well outlined by air. The larynx is ventral to the first two cervical vertebrae. The bones of the hyoid are easily identified and should not be mistaken for foreign bodies. Mineralization of the laryngeal and tracheal cartilages is a common finding, particularly in older dogs and chondrodystrophic breeds. The normal larynx is slightly wider than the trachea.

• The trachea should be uniform in diameter throughout its length. The trachea is typically positioned to the right of midline in the cranial thorax. The cartilaginous tracheal rings are incomplete dorsally in the dog. Calculation of the ratio of tracheal diameter to thoracic inlet diameter is one way used to assess tracheal size. The normal ratio in non-brachycephalic breeds is 0.20 ± 0.03. The ratio is slightly smaller in brachycephalic breeds.

• The following structures should be visible on a normal thoracic radiograph: the cardiac silhouette, pulmonary arteries and veins, caudal vena cava, descending aorta, trachea, primary bronchi, diaphragm, and (in young animals) the thymus.

• The following structures are often not seen on a normal thoracic radiograph: the cranial vena cava; aortic arch; brachycephalic trunk; esophagus; secondary and tertiary bronchi; and the mediastinal, tracheobronchial, and sternal lymph nodes. It is not uncommon to see small amounts of gas in the cranial to mid-thoracic esophagus, particularly in a sedated or aerophagic animal. It is also not uncommon to see a small amount of fluid (soft tissue opacity) in the caudal thoracic esophagus, particularly when the animal is in left lateral recumbency.

• Radiographically the pulmonary vessels account for the majority of the pulmonary patterns observed on normal films. The pulmonary arteries and veins should be matched in size.

• On the lateral thoracic radiograph, the artery lies dorsal to its corresponding vein. On the dorsoventral (DV) or ventrodorsal (VD) radiograph, the artery lies abaxial to its corresponding vein. Hence, veins are central and ventral relative to their corresponding arteries.

• On the lateral radiograph, the diameter of the cranial lobar vessels should be roughly the width of the fourth rib as it crosses that rib. The diameter of the caudal lobar vessels should be roughly the width of the ninth rib as it crosses that rib. Vessels should be linear, soft tissue opacities that taper toward the periphery of the lung.

TECHNICAL CONSIDERATIONS

• Inspiratory and expiratory radiographs with the patient in lateral recumbency may be used to demonstrate dynamic tracheal or bronchial collapse if fluoroscopic imaging is unavailable.

• Inspiratory and expiratory radiographs with the patient in DV or VD positioning may be used to demonstrate diaphragmatic paralysis if fluoroscopic imaging is unavailable.

• For animals with moderate to severe pleural effusion, if a VD is tolerated, it is preferred to the DV radiograph to better assess the cardiac silhouette and pulmonary parenchyma. Pleural effusion will increase the overall opacity of the pulmonary structures due to summation. Also, pulmonary opacity will increase due to lung underinflation secondary to fluid in the pleural space.

RADIOGRAPHIC ABNORMALITIES OF THE NASAL CAVITY

• Rhinitis and neoplasia may cause focal or diffuse increases in radiographic opacity of the nasal passage. Turbinate destruction is often present in animals with neoplasia or erosive rhinitis. Most cases of bacterial or foreign body rhinitis involve the rostral and middle portions of one or both nasal passages. Most nasal neoplasms originate from one nasal passage but may extend into the other.

• Fungal rhinitis, such as aspergillosis, often causes osteomyelitis with a productive osseous component, most notably involving the frontal sinuses. There may be a diffuse decrease in radiographic opacity of the nasal passages due to the complete destruction of turbinates, which is followed by the animal sneezing them out. Fungal rhinitis often involves the entire nasal cavity.

• Neoplastic processes often appear more destructive than rhinitis. The mass effect caused by some neoplasms may result in displacement of normal nasal structures and distortion of anatomical structures. Definitive diagnosis of nasal disease is generally not possible radiographically. Rhinoscopy with biopsy, cytology, and/or culture is necessary.

RADIOGRAPHIC ABNORMALITIES OF THE NASOPHARYNX, OROPHARYNX, AND LARYNX

• Upper airway diseases such as brachycephalic upper airway obstruction syndrome, laryngeal paralysis, and laryngospasm are best evaluated using visual examination externally or endoscopically.

• Masses, such as neoplasia, nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal polyps, abscesses, and granulomas, may appear radiographically as soft tissue opacities within the airways. These masses may or may not have internal mineralization.

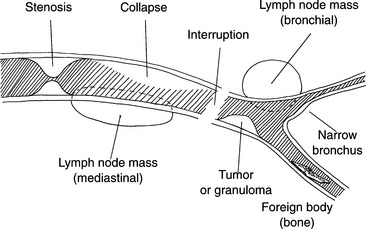

RADIOGRAPHIC ABNORMALITIES OF THE TRACHEA (Fig. 159-1)

• Tracheal hypoplasia is a congenital disorder seen most commonly in brachycephalic breeds, particularly English Bulldogs. The tracheal diameter is diffusely decreased and in severe cases, the ratio of tracheal diameter to thoracic inlet diameter may be reduced to less than 0.10.

• Tracheal displacement by regional soft tissues is a reliable sign of mass lesions once positioning artifacts and breed characteristics have been considered.

• Except for tracheobronchial and mediastinal lymphadenopathy and severe cardiomegaly, lesions causing significant attenuation of the tracheal lumen usually originate within the trachea.

• Masses, such as neoplasia, polyps, abscesses, granulomas, and foreign bodies, may appear radiographically as soft tissue opacities within the airways. These masses may or may not have internal mineralization. Tracheal neoplasia is rare in small animal patients.

• Tracheitis, secondary to upper airway inflammation, may cause transient luminal narrowing due to tracheal mucosal swelling and must not be incorrectly diagnosed as tracheal hypoplasia.

• Tracheal perforation usually occurs in the thoracic inlet portion of the trachea and results in subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, and often pneumoretroperitoneum. Occasionally, a pneumomediastinum may progress to a pneumothorax.

• Complete tracheal rupture is an uncommon, life-threatening event. In addition to severe peritracheal air accumulation, discontinuity of the tracheal wall is seen with separation of the tracheal rings. This is best assessed on the lateral radiographic view. This occurs most commonly in cats just cranial to the heart base.

• Focal tracheal stenosis is most commonly secondary to previous trauma (i.e., dog fight, prolonged over-inflation of endotracheal tube cuff) with resultant stricture.

• Tracheal collapse is usually dynamic in nature, resulting in variation of tracheal diameter relative to the phase of the respiratory cycle. Tracheal collapse is often exacerbated during periods of excitement or during coughing. This is most commonly seen in toy breed dogs prone to loss of structural rigidity of the trachea and mainstem bronchi secondary to chondromalacia. To adequately assess tracheal dynamics, lateral thoracic radiographs are needed. These should be taken during peaks of inspiration and expiration, and should include the caudal neck. The cervical and thoracic inlet portions of the trachea collapse during inspiration, whereas the intrathoracic portion of the trachea and mainstem bronchi collapses during expiration.

RADIOGRAPHIC ABNORMALITIES OF THE EXTRAPLEURAL SPACE

• The extrapleural space communicates with many of the fascial planes of the body via the thoracic inlet. It can be divided into two areas:

• Conditions affecting the extrapleural space include abscesses, hematomas, granulomas, and neoplasms.

• Radiographically, most extrapleural diseases appear as relatively spherical, smoothly marginated masses that have a convex border facing the lung with tapering or concave cranial and caudal margins (the extrapleural sign).

• Thymic masses, mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and rib tumors with osteolysis are common extrapleural lesions.

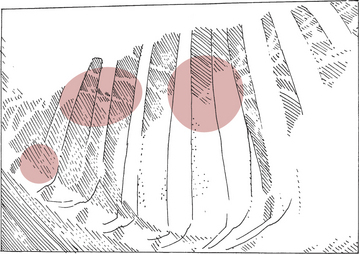

Thoracic Lymph Nodes (Fig. 159-2)

The thoracic lymph nodes are located in three areas within the mediastinum:

• Hilar area of lung surrounding the bifurcation of the mainstem bronchi from the trachea (tracheobronchial lymph nodes)

• Cranial mediastinal lymphadenomegaly may cause apparent widening of the cranial mediastinum on the DV or VD radiographic view, and dorsal displacement of the trachea on the lateral radiographic view.

• Enlargement of the tracheobronchial lymph nodes may compress the mainstem bronchi abaxially and ventrally. On the VD or DV radiographic view, this splaying of the mainstem bronchi can mimic the radiographic appearance of left atrial enlargement. However, on the lateral radiographic view, tracheobronchial lymphadenomegaly causes ventral displacement of the mainstem bronchi, whereas left atrial enlargement would cause dorsal deviation of the mainstem bronchi.

Pneumomediastinum

This condition enables radiographic identification of the normally invisible mediastinal structures such as the esophagus, cranial vena cava, brachiocephalic artery, and other mediastinal vessels.

Pneumothorax may occur secondary to pneumomediastinum; however, the reverse does not occur.

RADIOGRAPHIC ABNORMALITIES OF THE PLEURAL SPACE

Pleural Effusion

• Pleural effusion is characterized by increased soft-tissue opacity within the pleural space that changes in distribution depending on patient positioning. It is not possible to radiographically determine the type of effusion within the pleural space; thus, thoracocentesis with fluid analysis is necessary to reach a definitive diagnosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree