Chapter 34 Diabetes Mellitus

ETIOLOGY

Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus

• Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), also referred to as type 1 diabetes, is a diabetic state in which endogenous insulin secretion is never sufficient to prevent ketone production.

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

• Non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM), also referred to as type 2 diabetes, is a diabetic state in which insulin secretion is usually sufficient to prevent ketosis but not enough to prevent hyperglycemia.

• Insulin secretion may be high, low, or normal but is insufficient to overcome insulin resistance in peripheral tissues.

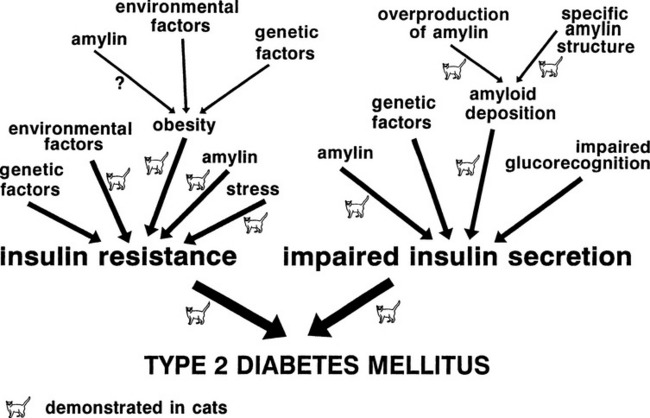

• The metabolic hallmarks of type 2 diabetes are impaired insulin secretion, increased hepatic glucose output, and insulin resistance (Fig. 34-1).

• In cats and in humans with type 2 diabetes, insulin secretion secondary to a glucose load is impaired. The early phase of insulin secretion is delayed or absent, and the second phase of insulin secretion is delayed but exaggerated.

• Amyloid deposition in the pancreatic islets may be the cause of impaired insulin secretion in cats.

Type 3 Diabetes Mellitus

• Type 3, or secondary, diabetes mellitus is the result of another primary disease or drug therapy that produces insulin resistance (e.g., hyperadrenocorticism, hyperthyroidism, acromegaly, or progestational drugs) or destroys pancreatic tissue (pancreatitis). Secondary diabetes is common in both dogs (pancreatitis) and cats (drugs, endocrinopathies, pancreatitis).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Uncomplicated Diabetes Mellitus

• In animals with uncomplicated diabetes mellitus, hyperglycemia results from impaired glucose utilization, increased gluconeogenesis, and increased hepatic glycogenolysis.

• Decreased peripheral utilization of glucose leads to hyperglycemia followed by osmotic diuresis. This causes the classic clinical signs of polyuria with compensatory polydipsia and progressive dehydration.

• Impaired glucose utilization by the hypothalamic satiety center combined with loss of calories in the form of glycosuria results in polyphagia and weight loss, respectively.

• Insulin is anabolic; therefore, insulin deficiency leads to protein catabolism and contributes to weight loss and muscle atrophy.

• As a consequence of protein catabolism, amino acids are used by the liver to promote gluconeogenesis and contribute to hyperglycemia.

Complicated (Ketoacidotic) Diabetes Mellitus

• With time, uncomplicated diabetes mellitus may progress to complicated or ketoacidotic diabetes. In these animals, insulin deficiency causes abnormal lipid metabolism in the liver such that non-esterified fatty acids are converted to acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) rather than being incorporated into triglycerides.

• Acetyl-CoA accumulates in the liver and is converted into acetoacetyl-CoA and then ultimately to acetoacetic acid. Finally, the liver starts to generate ketones including acetoacetic acid, beta-hydroxybutyrate, and acetone.

• As insulin deficiency culminates in DKA, accumulation of ketones and lactic acid in the blood and loss of electrolytes and water in the urine results in profound dehydration, hypovolemia, metabolic acidosis, and shock.

• Ketonuria and osmotic diuresis caused by glycosuria result in sodium and potassium loss in the urine and exacerbation of hypovolemia and dehydration.

• Nausea, anorexia, and vomiting, caused by stimulation of the chemoreceptor trigger zone via ketonemia and hyperglycemia, contribute to the dehydration caused by osmotic diuresis.

• Dehydration and shock lead to prerenal azotemia and a decline in the glomerular filtration rate. This declining rate leads to further accumulation of glucose and ketones in the blood.

• Stress hormones such as cortisol and epineph-rine contribute to the hyperglycemia in a vicious cycle.

CLINICAL SIGNS

Uncomplicated Diabetes Mellitus

• Acute onset of blindness caused by bilateral cataract formation is a common presenting complaint of diabetes mellitus in dogs.

• Cats may present with chronic complications of diabetes, such as diabetic neuropathy leading to gait abnormalities, plantigrade stance, difficulty jumping, and inappropriate elimination. Chronic gastrointestinal signs such as vomiting, diarrhea, and anorexia may also result from concurrent pancreatitis or from autonomic neuropathy.

Complicated (Ketoacidotic) Diabetes Mellitus

• Depression, vomiting, anorexia, and weakness are the most common clinical signs of ketoacidosis in dogs and cats.

• Physical examination findings may include depression, tachypnea, dehydration, weakness, vomiting, and occasionally, a strong acetone odor on the breath.

• Cats may present recumbent or comatose, which may be a manifestation of severe ketoacidosis or mixed ketotic hyperosmolar syndrome.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinicopathologic Findings in Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Findings in DKA may include all of the above findings plus the following:

Diagnostic Pitfalls

• With regard to fasting hyperglycemia, many cats are susceptible to “stress-induced” hyperglycemia in which the serum glucose concentrations may approach 300 to 400 mg/dl.

• Renal glycosuria may be found in animals with renal tubular disease and occasionally with stress-induced hyperglycemia.

TREATMENT OF DIABETIC KETOACIDOSIS

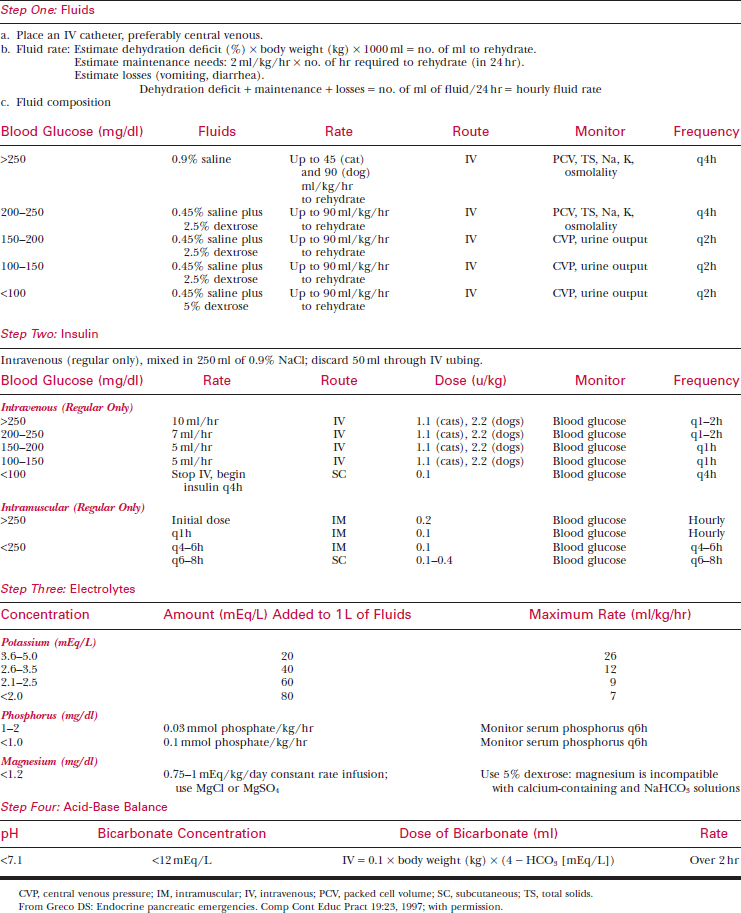

Treatment of DKA, as outlined in Table 34-1, includes the following steps in order of importance:

1. Fluid therapy using 0.9% saline initially, followed by 2.5% or 5% dextrose as serum glucose declines

Fluid Therapy

• Use 0.9% NaCl supplemented with potassium as the fluid therapy of choice when insulin therapy is initiated (see Table 34-1).

• Administer fluid therapy using a large central venous catheter, as animals in DKA are severely dehydrated and require rapid fluid administration; central venous pressure may also be monitored via a jugular catheter to avoid overhydration.

Insulin Therapy

Initiate insulin therapy as soon as possible using either IV insulin or low-dose IM methods. Administer IV insulin via a separate peripheral catheter using the guidelines in Table 34-1.

• The species of origin of regular insulin (beef, pork, or human) does not affect response; however, the type of insulin given is very important. Use only regular insulin because it has a rapid onset and short duration of action and it can be given IV. Never give Lente, Ultralente, or NPH insulin IV.

• Allow approximately 50 ml of fluid and insulin mixture to flow through the IV drip set and discard it, because insulin binds to the plastic tubing.

• With IV insulin administration, blood glucose decreases to below 250 mg/dl by approximately 10 hours in dogs and after about 16 hours in cats.

• Once euglycemia has been achieved, maintain the animal on SC regular insulin (0.1-0.4 U/kg q4-6h SC) until it starts to eat and/or the ketosis has resolved.

Electrolyte Supplementation

Potassium

• Although serum potassium may be normal or elevated in ketoacidosis, the animal actually suffers from total body depletion of potassium. Correction of the metabolic acidosis tends to drive potassium intracellularly in exchange for hydrogen ions. Insulin facilitates this exchange, and the net effect is a dramatic decrease in serum potassium, which must be attenuated with appropriate potassium supplementation in fluids.

Magnesium

• Refractory hypokalemia may be complicated by hypomagnesemia. Supplementation of magnesium along with potassium as outlined in Table 34-1 may be indicated in cats or dogs with hypokalemia that are unresponsive to potassium chloride supplementation in fluids.

Phosphorus

• Serum and tissue phosphorus may also be depleted during a ketoacidotic crisis; thus, supplement one-third of the potassium dose as potassium phosphate (see Table 34-1), particularly in small dogs and cats that are most susceptible to hemolysis caused by hypophosphatemia.

• Use caution, as oversupplementation of phos-phorus can result in metastatic calcification and hypocalcemia.