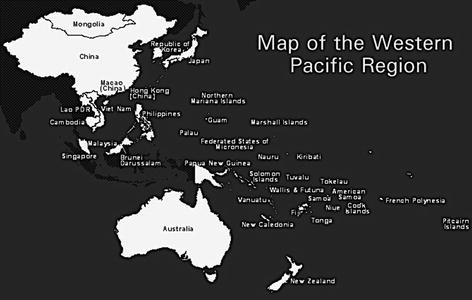

1. American Samoa

11. Japan

21. New Zealand

29. Samoa

2. Australia

12. Kiribati

22. Niue

30. Singapore

3. Brunei Darussalam

13. Lao People’s Democratic Republic

23. Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands

31. Solomon Islands

4. Cambodia

32. Tokelau (New Zealand)

5. PR China

14. Macao (China)

6. Cook Islands

15. Malaysia

24. Palau

33. Tonga

7. Fiji

16. Marshall Islands

25. Papua New Guinea

34. Tuvalu

8. French Polynesia (France)

17. Micronesia, Federated States of

26. Philippines

35. Vanuatu

27. Pitcairn Islands (UK)

36. Vietnam

9. Guam (USA)

18. Mongolia

28. Republic of Korea

37. Wallis & Futuna

10. Hong Kong (China)

19. Nauru

20. New Caledonia (France)

The emergence of a series of novel zoonotic infections from the region in the last decade triggered an unprecedented mobilization of the international public health community to address these threats. SARS in 2003, exposed weaknesses in national capacities to quickly identify, contain, and control a novel infection; these weaknesses equate to a persisting global threat. In 1997 and then again in 2004, bird flu (Influenza A/H5N1), the largest epizoonosis ever recorded, sounded a second call for global pandemic preparedness highlighting not only the shortcomings of human health services but the challenges of strengthening animal health and production systems, of restructuring food supply chains, and of sustaining responses for years. The virus remains endemic in poultry in China and Vietnam and has demanded far more than just emergency responses.

There is recognition that strategies to reduce the likelihood of disease emergence and transmission by addressing underlying risks and vulnerabilities in the complex interactions among people, animals, and environments, between human systems and natural ecosystems, may be a better way to counter emerging diseases. This has been referred to in various contexts as ecohealth (Charron 2012), particularly where it includes consideration of the role of environmental factors, and as a One Health approach in which health disciplines work together rather than in exclusion. This “One Health” approach is pertinent to the Western Pacific Region for three reasons.

First, the Mekong subregion within the Western Pacific Region has been designated a “hot spot” for the emergence of novel diseases from wildlife because of an amalgam of related anthropogenic drivers of disease emergence: rapid economic development, urbanization, advancing farming systems, demand for livestock products and deforestation, as well as population increases and aging (Jones et al. 2008). These factors cannot be addressed by the human or animal health sectors alone, necessitating a collective engagement with a range of sectors and communities.

Second, unexpected epidemics of re-emerging zoonotic diseases including rabies, anthrax, and leptospirosis have caused morbidity and mortality in urban and peri-urban communities in the Western Pacific Region. Some of these epidemics are being addressed using One Health approaches, and indicate the value in learning from and working with partners in the region when developing public awareness and preparedness plans for emerging infectious diseases (EIDs).

Third, the region remains a sanctuary for well-known zoonotic infections such as brucellosis that have been eliminated in many parts of the world but may be effectively addressed with an approach that is better tuned to tackle the complexities of real-world problems (World Bank 2009).

It is fitting then, that serious global commitment to this nascent approach was made in the region in Hanoi in 2010: the International Ministerial Conference on Animal and Pandemic Influenza aimed to “set the scene for a worldwide effort, over the next 20 years” declaring the “…need for sustained, well-coordinated, multi-sector, multi-disciplinary, community-based actions to address high impact disease threats that arise at the animal-human-environment interface.”(UNSIC 2010).

2 Relevant Global and International One Health Endeavors in the Western Pacific Region

Numerous overlapping global and international initiatives from various consortia, donors, research institutes, and United Nations (UN) agencies are being implemented in the Western Pacific Region. While some initiatives have committed to improve coordination through systemic measures such as the One World, One Health initiative (FAO et al. 2008) and the FAO–OIE–WHO collaboration concept note on health risks at the human–animal interface (WHO et al. 2008), there is no overarching coordination of the multitude of activities being conducted in the region under a broad interpretation of One Health—this was emphasized at the recent Davos One Health summit with a major conclusion being the need to “intensify the collaboration and coordination between the leading and relevant…institutions in the broader One Health area” (Ammann 2012). In general, there are also no direct links with other global endeavors such as the Millennium Development Goals (UN Web Services Section 2010) and the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005).

Some of the global/international initiatives and organizations implementing these activities in the Western Pacific Region are listed below (Table 2). Only a selected number will be discussed in this chapter. This is an incomplete listing, but is illustrative of both the variety of work being addressed by various actors and institutions and the numerous (separate) networks operating in an environment of a broader One Health movement.

Table 2

Selected global One Health initiatives and organizations implementing One Health activities in the Western Pacific Region

Chatham House Centre on Global Health Security | Global Initiative for Food Systems Leadership (GIFSL) |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) One Health Office (OHO) | |

Health and Ecosystems: Analysis of Linkages (HEAL) | |

Connecting Organizations for Regional Disease Surveillance (CHORDS) | International Development Research Centre (IDRC) |

Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) | International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) |

DISCONTOOLS | Office International des Epizooties (OIE) Performance of Veterinary Services |

International Association for Ecology and Health | |

One Health Commission | |

EcoHealth Alliance | One Health Initiative |

EcoHealth Network | One World, One Health Initiative |

EcoHealth International Association for Ecology and Health | Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH) |

EcoHealth–One Health Resource Centers, Chiang Mai University and Gadja Mada University | Towards a Safer World |

Veterinarians Without Borders/Vétérinaires sans Frontières-Canada | |

Emerging Pandemic Threats (EPT) Program, USAID | |

World Bank Trust Fund for Avian Influenza | |

Epizone European Research Group | World Health Organization (WHO) Department of Food Safety and Zoonoses |

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) | World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) |

World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) | |

Global Early Warning System for Animal Diseases, Including Zoonoses (GLEWS) | |

Global Framework for the Progressive Control of Transboundary Animal Diseases (GF-TADs) |

3 Selected Regional and Multicountry Steps Towards Operationalizing One Health

Western Pacific ministries of Health and Agriculture have had experience of being abruptly forced to work together in new ways to address new diseases. Not all interactions have been successful, and efforts to date have not yet fully embraced a One Health approach, as most stakeholders currently understand it; rather, most initiatives are continuing efforts to combat key EIDs. There are, however, a number of endeavors that illustrate the movement towards One Health. Most of these initiatives are at the regional rather than the national or community levels.

3.1 Regional Strategies

3.1.1 Asia Pacific Strategy for Emerging Diseases

The cornerstone of regional plans to confront EIDs is the Asia Pacific Strategy for Emerging Diseases (APSED) (World Health Organization 2010; World Health Organization, Western Pacific Region 2010). This is essentially a “health security” construct aiming to strengthen national systems to comply with the legal requirements of the International Health Regulations (2005) (World Health Organization 2005) and to improve national capacity to combat EIDs. The latest iteration of the strategy (2010) drew heavily on the lessons learned from the 2009 pandemic of influenza A/H1N1 and allows countries flexibility to decide how they can best achieve the vision of the eight areas of focus: (1) surveillance, risk assessment, and response; (2) laboratories; (3) zoonoses; (4) infection prevention and control; (5) risk communications; (6) public health emergency preparedness; (7) regional preparedness, alert, and response; and (8) monitoring and evaluation. The Emerging Disease Surveillance and Response unit of the WHO is responsible for assisting countries to implement APSED. APSED is not a One Health vision, however, lacking the synergies between all sectors whose activities impact on health.

3.1.2 Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation

Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) considers emerging diseases to be of high importance because of their preventability and the substantial direct (e.g., treatment and hospitalizations) and indirect (e.g., lost time to work, trade sanctions) costs that such diseases have caused to their 21 members states in recent years. Since 1996, APEC has supported the APEC Emerging Infections Network (APEC EINet 2012), a network that seeks to gather and disseminate notifications of EIDs affecting APEC member states, foster collaborations among academic institutes, government, and business where they relate to EIDs, and enhance regional biopreparedness. This mechanism is useful for dialog between sectors beyond just the animal and human health sectors, although the degree of communication and idea sharing does not approach the transdisciplinarity advocated by most One Health proponents.

Nonetheless, APEC did fund the Technology Foresight Project (2006–2007) (The APEC Center for Technology Foresight National Science and Development Technology Agency 2008; Damrongchai et al. 2010), a succinct effort in transdisciplinarity that brought together a range of experts from policy makers and technology developers to virologists and economists to map the convergence of new technologies and the opportunities for their accelerated development in order to limit the human and financial impact of novel diseases. While narrowly focused on the technological aspects of disease prevention and control, and a project rather than an ongoing, inbuilt process, this work encompassed the development of new vaccines, treatments, diagnostics, models and simulations, and tracking strategies for people and animals.

APEC have since drafted a One Health Action Plan (Asia–Pacific Economic Cooperation 2011) setting out a common “vision” for member states to operationalize One Health approaches according to their capacities and level of engagement with the concept. The plan aims to strengthen cross-sectoral efforts at the political and leadership level, in teaching and training, in (government) functions to prevent, investigate, respond and control diseases, and across borders. The community is identified as a critical partner in disease prevention and control, and action to ensure the sustainability of cross-sectoral approaches is called for.

3.1.3 ASEAN

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has defined a roadmap to prevent, control, and eradicate highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) and other highly pathogenic emerging diseases among member states by 2020 using a risk-based approach to address the major transmission pathways in each country (ASEAN Secretariat 2010a). The roadmap describes itself as a “translation” of the One Health approach to systematically eradicate HPAI, while simultaneously addressing other transboundary and zoonotic diseases. While the focus is on animal health and production, the advantages of engaging with multiple disciplines, multiple sectors, and multiple agencies are noted.

This is an encouraging output from ASEAN, but is one of the few documented instances of ASEAN activities related to One Health, either in progress or completed. Furthermore, the emphasis on HPAI rather than a broader One Health approach potentially misses an opportunity to embrace a wider notion of health including the role of wildlife, the integration of resources from various health and nonhealth authorities, as well as concrete plans for regular communication across health and related disciplines. ASEAN is in a unique position to be the premier institution in Asia coordinating, influencing, and even governing to some degree an integrated One Health approach for part of the Western Pacific Region. The HPAI roadmap is a step in the right direction but much remains to be done if ASEAN is to be a One Health leader. ASEAN’s biggest challenge may be the reluctance of member nations to advise on what others should be doing. This is, however, a requirement for an integrated One Health network to be effective among the member states.

The ASEAN Plus Three EIDs Programme has improved joint country investigations of disease outbreaks and developed a regional risk communication strategy (ASEAN Secretariat 2010b). A new program funded by the Japanese Government is directed at improving laboratory capacity and networking (ASEAN Secretariat 2009), continuing a long and successful history of Japanese funding to develop diagnostic and research laboratory capabilities in the region.

3.1.4 The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Regional Strategy for Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza and other EIDs of Animals in Asia and the Pacific, 2010–2015 (Emergency Centre For Transboundary Animal Diseases 2010) outlines a common approach for dealing with endemic HPAI and for addressing emerging and re-emerging diseases. The strategy also aims to join up the fragmented support provided by various partners and donor agencies within the region. This is the latest in a series of initiatives led by FAO and its partners to combat HPAI since the first outbreaks in Southeast Asia, initiatives that were themselves preceded by other efforts founded in One Health concepts including the FAO Emergency Prevention System (EMPRES) and the Global Framework for the Progressive Control of Transboundary Animal Diseases (GF-TADs).

3.1.5 Donor Strategies

Most of the major Pacific Basin donors have made significant contributions to initiatives to address emerging diseases. The Public Health Agency of Canada leads the Canada–Asia Regional Emerging Infectious Disease (CAREID) Project aiming to strengthen the capacity of Cambodia, Laos PDR, the Philippines, and Vietnam to detect and respond to emerging diseases (Public Health Agency of Canada 2012). Similarly, the Australian Government’s international development assistance agency has articulated a regional strategy for strengthening health systems to respond more generally to EIDs: the Pandemics and EIDs Framework 2010–2015 (AusAID 2010). The Asian Development Bank has implemented a series of communicable diseases control projects along borders in the Greater Mekong region to improve community surveillance of endemic and epidemic diseases including EIDs (Asian Development Bank 2012). And the USAID Emerging Pandemic Threats Program (U.S. Agency for International Development 2010) operates globally with specific activities related to four project areas in Southeast Asia: wildlife pathogen detection, risk determination and reduction, outbreak response capacity, and institutionalization of a One Health approach. This last element is elaborated on in the next section (Academic Initiatives).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree