Chapter 1 Dental Records

• Clear, concise, complete dental records are important for all patients undergoing oral and dental examination and treatment. Records are the most critical evidence that can be presented in court, at any level, as confirmation of accurate diagnosis and proper treatment. Good records are the best way to defend against unjustified malpractice claims. A standard of care does not require perfection, but rather a reasonable degree of skill, knowledge, and competence exercised by doctors under similar circumstances. As the level of veterinary dentistry rises during the twenty-first century, it behooves general practitioners either to develop an increased level of dental skill or at least to increase their knowledge to a point of being able to refer to an appropriate clinician a case in need of treatment.1

• Written records are necessary to identify the patient; to record the patient’s status before, during, and after treatment procedures; to document client acceptance or rejection of the treatment plan; to record therapy sequence, prognosis, results, and sequelae; to measure progress at successive appointments; to document consultations and referrals; and to provide ease of transfer to another practitioner.2

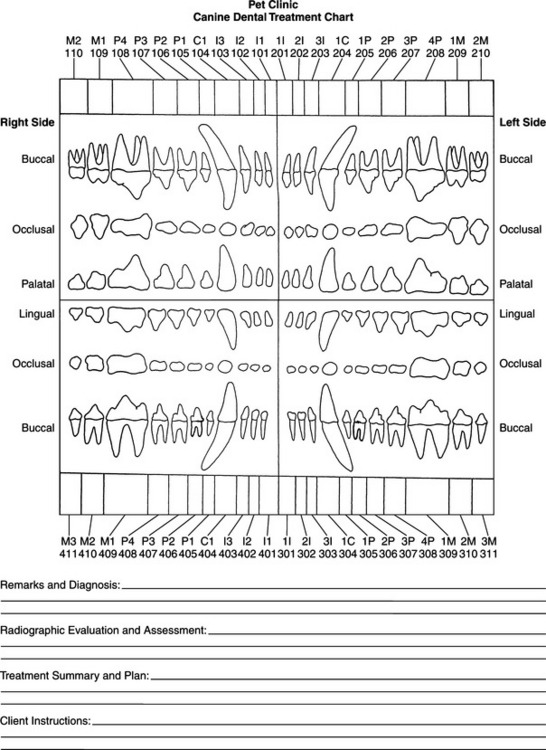

• Dental charts are a convenient conveyance for reducing the amount of writing, as well as increasing the visual comprehension. They serve well for the application of abbreviations and schematic treatment references of anatomic abnormalities, a patient’s condition, performed periodontal, endodontic, and surgical therapy modalities, and for evaluating the response to treatment by comparison with charted information on recall visits. Good records are the best way to defend against unjustified malpractice claims.3 The paperless practice is a buzzword of the turn of the century, but to be a legally defendable record it should be unalterable. Too many “paperless” practices rely on invoice-driven programs, itemizing services performed or products sold, but not justifying the treatment administered or the products dispensed. Likewise, many records interchange the reason for patient presentation with the diagnosis, and they are not at all the same. A diagnosis (definitive diagnosis) is derived from a combination of history taken (subjective information), observations (objective data of signs, symptoms, or laboratory evaluations), and an assessment that rules out differential diagnoses suggested from objective data gathered. A diagnosis is justified by the historical and objective data; it is not necessarily what the client believes is the problem or the reason written in the clinician’s schedule for the appointment.

• There is one other important legal aspect concerning records. Each entry in the dental record should be initialed by the person responsible for the entry. In computerized records, that means that a provider code should be entered and one should be assigned to all staff members.

• The American Veterinary Dental College (AVDC), in its Position Statement for Dental Health Care Providers,4 defines veterinary dentistry as “… the art and practice of oral health care in animals other than man. It is a discipline of veterinary medicine and surgery. The diagnosis, treatment, and management of veterinary oral health care is to be provided and supervised by licensed veterinarians or by veterinarians working within a university or industry.” The AVDC has developed this position as a means to safeguard the veterinary dental patient and to ensure the qualifications of persons performing veterinary dental procedures. It is not a legal position, but one set by leaders of the veterinary dental profession. The practice acts of all but nine states in the United States legally consider tooth extraction a surgical procedure. Surgery alters the anatomy of the patient and, as such, should be performed by qualified doctors. The AVDC position accepts “that the following health care workers may assist the responsible veterinarian in dental procedures or actually perform dental prophylactic services while under direct, in-the-room supervision by a veterinarian if permitted by local law: licensed, certified, or registered veterinary technician, or a veterinary assistant with advanced dental training, dentist, or registered dental hygienist.”4

• The AVDC supports the advanced training of veterinary technicians and assistants to perform additional ancillary dental services: taking impressions, making models, charting veterinary dental pathology, taking and developing dental radiographs, performing nonsurgical subgingival root scaling and debridement, providing that they do not alter the structure of the tooth (see Appendix.)

• The reader has the authors’ permission to use the dental charts in this text in the course of practice.

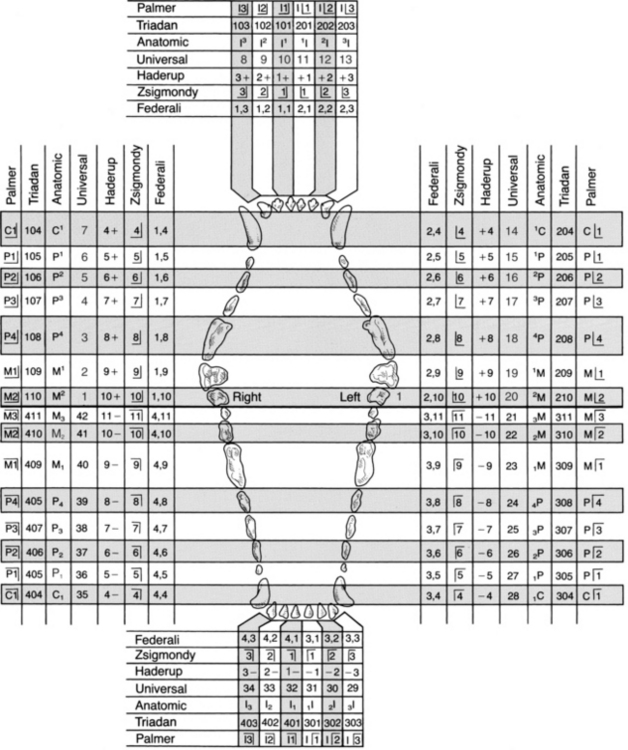

TOOTH IDENTIFICATION SYSTEMS

General Comments

• In some systems a number is given to each tooth, whereas other systems use numbers and symbols to designate a tooth. The systems that use numbers alone are more readily adaptable for use with computers.

• This text uses the terms type to refer to primary (deciduous) or secondary (permanent) dentition and function to refer to the four common functional groups: incisor, canine, premolar, and molar.

• The two most commonly used identification systems in veterinary dentistry are the modified Triadan system and the anatomic system.

MODIFIED TRIADAN SYSTEM

General Comments

• The modified Triadan system has been described in numerous texts. Each tooth is given a three-digit number.5,6

• The first number represents the quadrant, with the maxillary right quadrant being 1. Looking at a dental chart, the system is set up to reflect the clinician who is looking at the patient that is looking back at him or her. The quadrants seen on the chart, beginning with the maxillary right, are numbered sequentially in a clockwise fashion.

• For permanent teeth, the maxillary right quadrant is 1, the maxillary left quadrant is 2, the mandibular left quadrant is 3, and the mandibular right quadrant is 4. Quadrants for primary teeth are represented by 5, 6, 7, and 8, beginning again with the maxillary right quadrant as 5 and ending with the lower right as 8. The individual teeth are represented by two digits, with 01 being the first tooth from the midline and continuing distally along the arch to the last tooth. For dogs, the last number for secondary teeth is normally 10 for the upper arch and 11 for the lower arch.

• The rule of four and nine is used to simplify annotations among the various species. Tooth 4 is always the canine tooth and tooth 9 is always the first molar, in either the maxillary or mandibular arch. For example, 504 represents the primary maxillary right canine tooth, and 309 represents the secondary mandibular left first molar. In species such as the cat, where the maxillary first premolar is missing, the teeth on the secondary maxillary right side are 101, 102, 103, 104 (105 is missing), 106, 107, 108, and 109. The teeth in the feline right secondary mandibular arch are 401, 402, 403, 404, 407, 408, and 409 (405 and 406 are missing). The numbers are not used when a tooth is normally missing in a species.

Advantages

• Easy to use in dealing with a single species or when records with anatomic charts printed on them are used.

• Once learned, this system is easier to say and write in records when describing teeth involved in pathology or treatment.

ANATOMIC IDENTIFICATION SYSTEM and DENTAL SHORTHAND

General Comments

• Uppercase letters are used for secondary (permanent) teeth, and lowercase letters are used for primary (deciduous) teeth.

• Maxillary teeth are indicated by superscript numbers, and mandibular teeth are indicated by subscript numbers.

• Teeth on the patient’s right are indicated to the right side of the letter, and teeth on the patient’s left are indicated to the left side of the letter. In this system, unlike in most dental charts, the clinician and the patient are looking in the same direction; the patient’s right teeth are noted on the right, and the left ones on the left in the chart.

• The teeth are numbered consecutively, for each functional group of teeth, starting from the midline. This number is placed in the appropriate corner around the letter. For example:

Superscript and subscript numerals for the teeth on the animal’s right side are placed on the right side of the letter designating the functional group.

The permanent maxillary right central incisor is represented by the number 1 placed as a superscript on the right side of the uppercase letter I as: I1.

Second and third secondary mandibular left premolars are represented by the numbers 2 and 3 placed as a subscript on the left side of the uppercase letter P as: 3,2P.

Advantages

• May be used with alphanumeric systems by placing “U” (upper) or “L” (lower) or “+” or “–” for maxillary or mandibular, before or after the tooth number.

PALMER NOTATION SYSTEM

General Comments

• The teeth are numbered consecutively within their functional group, and a symbol is used to denote the quadrant. Note that right and left are as viewed and do not indicate the patient’s right and left.

NUMERICAL ORDER (UNIVERSAL TOOTH NUMBERING SYSTEM)

General Comments

• This system is commonly used in human dentistry and facilitates communication with this profession.

• Each permanent tooth is given a number 1 to 30 in the cat, 1 to 42 in the dog. Primary teeth are lettered (a to z in the cat; a to B in the dog).

• The teeth are numbered starting in the upper right quadrant with the last tooth and continuing with consecutive numbers around the arch to the opposite last upper left tooth. The lower arch is numbered starting from the last lower left tooth and continuing around the arch to the last lower right tooth.

HADERUP SYSTEM

General Comments

• The upper or lower arch is indicated by a + or – next to the number, with + corresponding to the upper jaw and – to the lower jaw.

ZSIGMONDY SYSTEM

General Comments

• This system uses a plus sign to identify quadrants. With the head of the patient facing the observer, visualize a horizontal line between the upper and lower jaws and a vertical line separating the right from the left side.

• The intersecting lines of this sign are used to show the corresponding quadrant. These are noted as viewed (not the patient’s right or left).

• The permanent teeth are numbered consecutively in each quadrant, starting from the midline. The primary teeth are lettered consecutively, starting with the letter A for the first tooth from the midline.

5 = permanent upper right first premolar in the dog.

4 = permanent lower left canine in the dog.

FÉDÉRATION DENTAIRE INTERNATIONALE SYSTEM

General Comments

• This system identifies each quadrant by numbers 1 to 4 for permanent teeth and 5 to 8 for primary teeth: 1/5 = upper right maxillary teeth, 2/6 = upper left maxillary teeth, 3/7 = lower left mandibular teeth, and 4/8 = lower right mandibular teeth.

• The teeth are numbered consecutively in each quadrant from the midline, with the corresponding quadrant number for the permanent or primary tooth in front of it separated by a comma.

VETERINARY MEDICAL RECORDS

General Comments

• In recording dental findings, written justification for treatment and procedures performed is necessary to substantiate a legal record. If that treatment is ever questioned, the record will reflect continuity of periodic treatment for various dental disorders.

• The medical record should contain the client’s name, address, and telephone number(s) and the name, breed, age, and gender of the patient.

• Having a telephone number where the client can be contacted during a patient’s dental procedure can be beneficial if additional abnormalities are found while the patient is anesthetized.

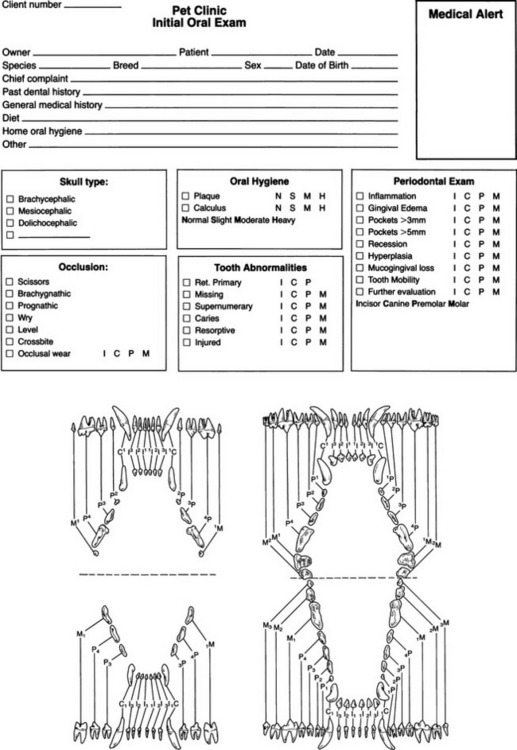

DENTAL RECORDS

General Comments

• Dental records also have legal ramifications and can consist of fill-in or check-off formats, dental anatomic charts, or a combination of these to provide efficient, shorthand recording.

• An adequate dental record provides subjective and objective information. It should contain enough information to justify the treatment performed and the materials used in that treatment, tooth by tooth. To provide an efficient record-keeping system, a chart should include a dental diagram with an abbreviation key so that abbreviations and diagrams, augmented by a brief description to clarify disease(s) and treatment protocols, can be read accurately by a person not in the field. An assessment of procedure(s) performed, interpretation of radiographs taken, a therapeutic plan, and a prognosis complete the functional dental record.

• Dental anatomic charts are important because three-dimensional objects are described that are often difficult to discuss in written terms. An anatomic chart facilitates the recording of sequential treatments. If repetitive and extensive treatment is performed, additional pages with ongoing notations permit treatment progress review at a glance.

• The type of record used will vary in each practice but should include patient and client identification, chief complaint, a general health history, dental history, tooth identification system used, specific findings, treatment plan, anesthetic drugs (with strengths or dosages and route of administration used), follow-up care recommended, radiographic interpretation, assessment of treatment, prognosis, documentation of discussions and consultations, missed appointments, or deviation from recommended follow-up, and documented informed consent. Additionally, it is particularly important to enter a recommended diagnostic procedure or therapy that is declined.

INITIAL ORAL EXAMINATION

Diet

• The patient’s current diet and amounts fed—whether moist or dry, prescription, commercial, or table scraps—should be recorded. Other treats fed and oral habits (fence chewing, bones, rocks, firewood collection, etc.) should be listed. Identifying types of chew and play toys available can also be helpful, because many can cause tooth damage (prepared cow hooves, tennis balls, hard plastic or nylon chews).

Recording Specific Findings

• The head and oral cavity are examined systematically, and initial findings and abnormalities are recorded.

• The face and jaw should be examined for symmetry, swellings, and any abnormalities of the salivary glands and regional lymph nodes.

• Tooth abnormalities, including retained primary teeth, missing teeth, and supernumerary teeth, should be noted. Other dental findings, such as carious lesions, resorptive lesions, dental trauma, and any other abnormalities, are noted by indicating the tooth involved and their location on the tooth.

• The periodontal status is recorded by noting gingival inflammation, gingival edema, significant periodontal pocket depth, gingival recession, gingival hyperplasia, attachment loss, and tooth mobility. Additional diagnostic evaluation that is recommended should be noted.

• In addition to dental tissue, the oral cavity in general should be examined for lesions. Lesions, if detected, may be described in a variety of different ways, but not limited to those in Table 1-1 (see also Oral Examination in Chapter 4).

Table 1-1 WORDS TO DESCRIBE ORAL INFLAMMATORY DISEASE

| Type categories | Descriptive term | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Duration | Acute | Having a short course |

| Chronic | Having a long, continued course | |

| Physical appearance | Vesicular | Small, blister-like |

| Bullous | Circumscribed, elevated lesion more than 5 mm in diameter | |

| Ulcerative | Loss of epithelial covering causing a gradual disintegration of tissues | |

| Proliferative | Growth by reproduction of similar cells | |

| Suppurative, | Inflammatory exudate formed within the tissues | |

| Fibrinous | Containing fibrous tissue, usually by degeneration | |

| Hemorrhagic | Containing the elements of blood | |

| Severity | Mild | Appreciated only after careful observation |

| Moderate | Readily apparent, but lacks visual and mental impact | |

| Severe | Immediate and forceful visual impact on viewer | |

| Spread | Focal | Discrete and well circumscribed |

| Multifocal | Well defined but numerous | |

| Diffuse | Substantial portion of affected region | |

| Location of inflammation | Glossitis | Inflammation of the tongue |

| Cheilitis | Inflammation of the lips | |

| Buccostomatitis | Inflammation of the inner cheek | |

| Pharyngitis | Inflammation of the pharynx | |

| Faucitis | Inflammation of the glossopalatine folds or angles of the mouth | |

| Palatitis | Inflammation of the palate | |

| Gingivitis | Inflammation of the gingiva | |

| Periodontitis | Inflammation of the periodontium |

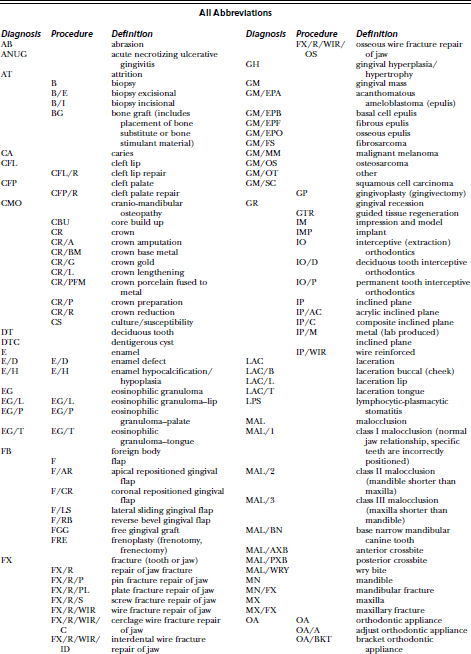

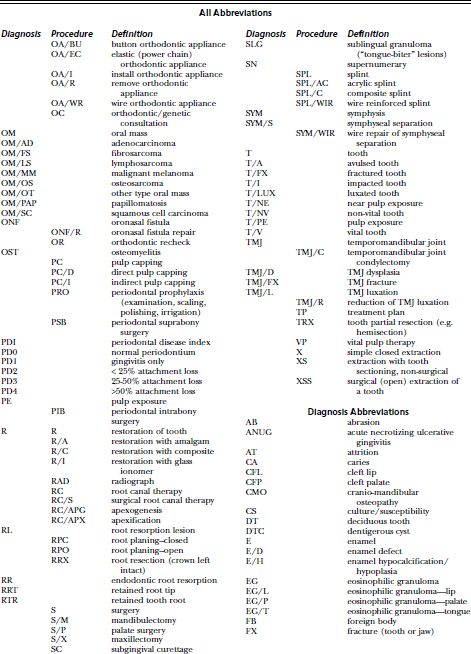

ANATOMIC CHARTING AND ABBREVIATED NOTATIONS

• Pathologic findings can be recorded on the anatomic chart. The chart is updated as the patient’s condition changes. This becomes the continuing record of the patient’s dental status.

• Symbols or letters to indicate a variety of abnormalities can be used on a dental anatomy chart to speed recording and allow a quick reference to all the abnormalities and treatments.

• A key for symbols and letter abbreviations used should be available to eliminate confusion for others reading the record.

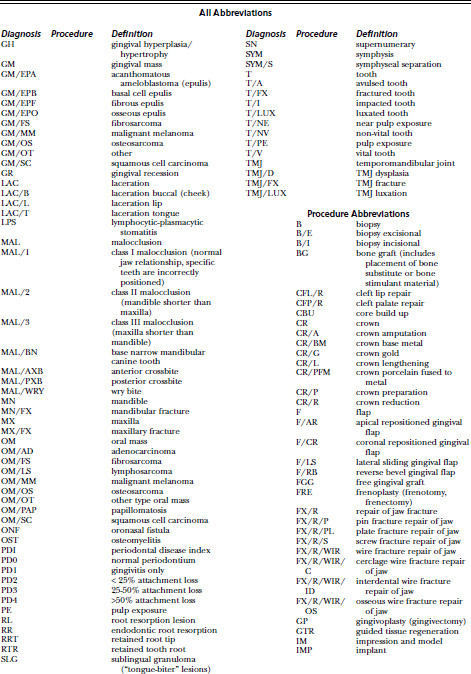

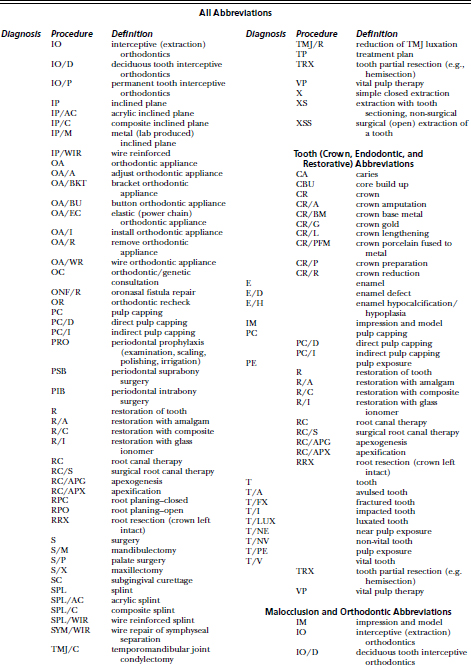

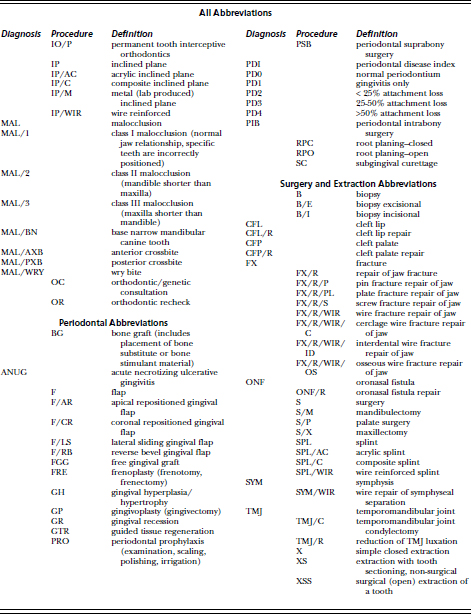

• The AVDC has adopted an extensive list of abbreviations and updated them in 20037(Table 1-2). The clinician can choose diagnoses and procedures most common in the practice and list these abbreviations and descriptions in an abbreviation key on the dental chart.

= upper left second permanent premolar.

= upper left second permanent premolar. = lower left first permanent premolar.

= lower left first permanent premolar. = lower right first permanent canine.

= lower right first permanent canine.