CHAPTER 113 Demographics and Herd Management Practices in South America

EARLY HISTORY

Current archeological evidence indicates that llamas and alpacas were domesticated in the Andean puna at elevations of 4000 to 4900 m above sea level.1 Identification of the ancestral forms from which they were domesticated, however, remains a matter of debate. Once these animals were domesticated, llama and alpaca herding economies spread beyond the puna limits and became important for Andean peoples living in all geographic regions, from sea level to high mountain elevations.2

THE PLACE OF ALPACAS AND LLAMAS IN THE ANDEAN ECOSYSTEM AND IN THE ANDEAN CULTURE

Since their domestication alpacas and llamas have played a critical role in the Andean agroecosystem. In the cold Andean highlands, as well as along parts of the Pacific Coast, the alpaca is the most important source of wool. The llama, also a secondary provider of wool, became a most efficient pack animal, enabling the transportation of goods over long distances. As remains true today in traditional villages, both species were a very important source of manure for agriculture, which also served as fuel in the high treeless puna environment. Although meat has always been considered of secondary importance in the Andean diet, salted and freeze-dried camelid meat is a potentially important source of high-quality protein.3

Camelid bones provide the raw material for work utensils and beautifully crafted items, whereas sinews are turned into thongs. Camelid lard, in addition to acknowledged health properties in the rich Andean medical lore, still plays an important role in religious rituals. Camelid fetuses resulting from natural abortion are still sold in rural markets and are widely used in fertility rites. Similarly, stone formation in the digestive system of alpacas and llamas—bezoars—are considered to be charms possessing medical and magical properties.3

Finally, and not least important, alpacas and llamas have always been an abundant source of images and concepts in the rich and metaphorical Andean ancestral mythology. Herders state that “we take care of our animals and they take care of us,”4 showing the strong interdependence of animals and humans. Peasants believe that pachamama (mother earth) gave alpacas and llamas to men as a loan, and that the future of humanity depends on the proper conservation of herds. They believe camelids originated in the underworld and came out from water springs. At the end of the world they will all return to those sacred springs. A sign that the end of the world is approaching, they say, will be depletion of the alpacas and llamas.3

Habitat

Along the western border of South America runs the high mountain range known as the Andes, or Cordillera de los Andes. These mountains are relatively young and are still in the process of being formed from the interaction of the South American and Pacific tectonic plates. Massive uplift has led to high, undulating land surfaces that contrast with the more continuous sharp relief of many other mountain systems.5

Faulting, folding, and volcanic activity have produced a rugged and mountainous surface topography, and glaciation and erosion have generated many deep valleys. The complex geologic history of the Andes has produced a landscape of rolling, relatively flat plateaus, with occasional mountain chains rising above them (approximately 6000 m above sea level) and deeply incised gorges cutting into them.5 The term puna is used to refer to this intermediate zone, ranging in altitude from 3700 to 4800 m above sea level.6 It has a relatively even terrain and its vegetation is characterized by bunch grasses and very sparse shrubs. It is this zone that constitutes the present-day habitat of the South American alpacas and llamas.

Two general climatologic seasons occur in this part of the Andean region: a mildly warm, rainy growing period from December to April and a cold, dry period from May to November. About 80% of the rainfall comes during the wet season, and the remaining 20% during the dry season in form of hail and snow (total rainfall of 300–900 mm). Weather data collected in the Department of Puno, where the La Raya High-Altitude Research Station is located, from 1931 to 1963 show the mean daily minimum temperature to be −3° C and the mean daily maximum temperature 17.3° C.7 As in other high-altitude regions, the diurnal variation in temperature is great, at times exceeding 30° C.8 This high-altitude environment is characterized by low atmospheric pressure, very dry climate, low oxygen availability, and intense solar radiation. In thin air, bodies absorb heat rapidly from the sun, and they lose it quickly when the rays of the sun are blocked by clouds. Moreover, wind, dry air, and low atmospheric pressure all are factors that increase the rate of evaporation.7

History of International Exportations

The first contact of Europeans with South American camelids probably was that of Captain Francisco Pizarro’s crew when he first arrived at the port of Tumbes in northern Perú, some time in 1528. Pizarro took some llamas back to Spain and displayed them at the Spaniard court. In those days, llamas were known by the Spaniards as carneros de la tierra (“rams of the land”) and later as carneros de cuello largo (“long-necked rams”).3 Since that time, many attempts were made to introduce members of the South American camelid family to Spain, England, France, Germany, and Holland during the 16th, 17th, and early 18th centuries. Some accounts of these introductions are available at the literature.9–11 By 1770 the government of Holland auctioned a herd of 32 alpacas and llamas belonging to King Wilfred II. It is said that this herd was purchased by the Frenchman Buffon, known in modern times as the “father of veterinary science,” and sent to the Veterinary School of Alfort, where the present-day museum’s exhibits include a beautiful dissection of a llama done by the anatomist Fragonard and hundreds of anatomic parts dissected by the best 18th century anatomists.

The greatest number of South American camelids ever carried to Europe at one time was a herd that arrived in Cadiz in 1808. It consisted of 36 animals, including llamas, alpacas, and vicuñas. They were brought from the highland of Peru to Buenos Aires, on the Atlantic Coast, by slowly travelling 2 to 3 leagues a day, and then shipped to Cadiz. Only 11 animals arrived at Cadiz alive, 2 of which died there. These animals were carried to Europe as a present from the Prince of Peace, Godoy, to Empress Josephine. In one report, six alpacas were imported to New Hampshire in the United States in 1849.3

One of the most interesting accounts of the introduction of alpacas and llamas to other countries is that of Charles Ledger, who wrote about his attempts to introduce them into Australia. He was particularly impressed by camelid adaptability: “No animal in the criation [sic], it is my firm conviction, is less affected by the changes of climate and food.” In 1858, he landed 274 animals in Sydney after 4 months at sea. In 1864, however, the Australian government decided to abandon the alpaca business entirely, under the duress of the merino sheep breeders, who saw in the alpaca a fine wool producer and a future competitor.12

Genetic Diversity, Distribution, and Number

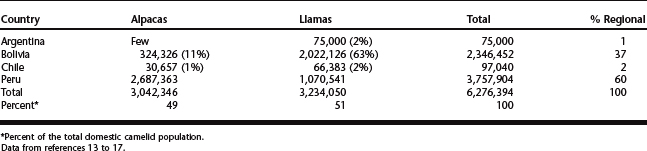

Available census data for current populations of llamas and alpacas in the Andean Region are presented in Table 113-1.13–17 The area of greatest concentration is located between 11 degrees south and 21 degrees south. Eighty-eight percent of the South American alpaca population are found in Peru. Likewise, the greatest population of llamas is found in Bolivia (62.5%). The rest of the alpaca and llama populations inhabit Chile and Argentina, and a very few are raised in Ecuador.

South American domestic camelids bred in different geographic zones of the Andean Mountains have sometimes been given local names, but it would be misleading to call them breeds. A survey carried out in 199113 studied the genetics of alpacas and llamas from Bolivia, Chile, and Peru, with the following findings:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree