Table 26.1 Instrument requirements for recumbent laparoscopic cryptorchidectomy

| Surgical table capable of tilting to 20°–30° (or overhead hoist capable of lifting the patient’s hindquarters) |

| Anesthetic machine with positive-pressure ventilator |

| Standard (general) surgery pack |

| Insufflator and CO2 source tubing |

| Light source, light cable, video camera, camera control unit, and monitor |

| 30° 10-mm telescope (33 or 57 cm—shorter telescope generally more convenient) |

| 3 laparoscopic cannulas (10 × 150 mm) |

| 1–2 laparoscopic grasping forceps (e.g., Semm) |

| Laparoscopic scissors |

| Ligating loop knot pusher with insert sleeve and ligature loops of 1 USP absorbable suture |

| Optional: |

| Electrocautery unit with monopolar or bipolar handpieces |

| or |

| Advanced bipolar or electromechanical instrument (e.g., LigaSure™ or equivalent or ultrasonic shears) |

Surgery

Port Position

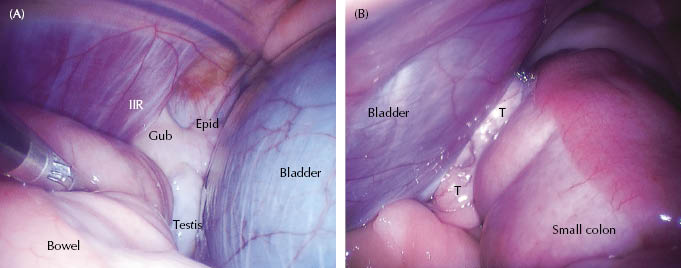

An initial telescope portal is usually made immediately cranial to the umbilical scar provided there is no reason to avoid this area (e.g., body wall–bowel adhesions from a previous abdominal procedure). While a teat cannula or Veress needle can be placed through the linea alba into the abdominal cavity to create pneumoperitoneum prior to placement of the telescope cannula, the author prefers to use an open (or modified Hasson) technique (Figure 26.2). Briefly, an 11- to 12-mm incision is made through the skin and the linea alba to the retroperitoneal space. A 10-mm cannula with a blunt obturator is used to perforate the parietal peritoneum. Once the cannula is safely placed in the abdominal cavity, an accomplishment generally confirmed with direct observation of viscera with the telescope in place, the horse can be repositioned into a 20°–25° Trendelenberg position while the abdomen is being insufflated. Inspection in the areas of both inguinal rings is mandatory to ascertain that there are no abnormalities other than the retained testicle(s). The pertinent anatomy is depicted in Figure 26.3. Typically, though not exclusively, the abdominally retained testicle is found adjacent to the urinary bladder and the corresponding inguinal ring (Figure 26.4). Often, the testicle can be located without the placement of an instrument portal. Conversely, on some occasions, it is situated dorsal to (underneath) a portion of the abdominal viscera near the pelvis, and an instrument is introduced to resituate some of those structures and to permit its identification and presentation.

Figure 26.2 Open (modified Hasson) technique for abdominal access. An 11- to 12-mm incision is made through the skin and the linea alba to the retroperitoneal space. A 10-mm cannula with a blunt obturator is used to perforate the parietal peritoneum, and successful entry into the abdominal cavity is visually verified.

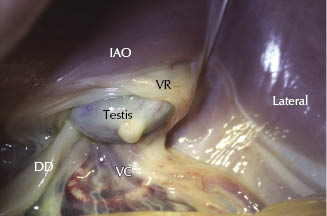

Figure 26.3 Dissection of a neonatal colt foal depicting the anatomy in the area of the internal inguinal ring. The testicle (testis) is protruding into the abdominal cavity through the elastic vaginal ring (VR). At approximately 2 weeks of age, the VR becomes sufficiently fibrous and stiff that migration of the testis through the ring is no longer possible. IAO, internal abdominal oblique muscle; DD, ductus deferens; VC, vascular cord.

Figure 26.4 (A) Endophotograph of structures adjacent to the left inguinal ring in an abdominal cryptorchid. The gubernaculum (Gub) can be seen entering the internal inguinal ring (IIR). It is attached to the tail of the epididymis (Epid) and testicle (testis), the latter of which is located between the loop of bowel under the grasping forceps and the urinary bladder. (B) Endophotograph of structures adjacent to the right inguinal ring in an abdominal cryptorchid. The retained testicle (T) can be seen between the urinary bladder and the small colon.

Two-Portal Technique

As suggested above, cryptorchidectomy can be conducted essentially as a “laparoscopic-assisted” open technique. Once satisfactory insufflation and Trendelenberg positioning is accomplished, the abdominal testicle is identified in the vicinity of the internal inguinal ring. A small parainguinal incision is made, typically craniomedial to the external inguinal ring, and a laparoscopic grasping forceps is introduced into the abdomen and the testicle grasped and advanced toward the ventral body wall. This incision is enlarged to accommodate the testicle, which is subsequently exteriorized. The spermatic cord is emasculated or ligated and transected extra-abdominally. Once hemostasis is assured, the spermatic cord stump can be returned to the abdomen, the pneumoperitoneum evacuated, the animal returned to level positioning, and the incisions closed by conventional means. This method is rapid, requires a minimum of specialized equipment, and leaves the inguinal ring structures intact.

Three-Portal Technique

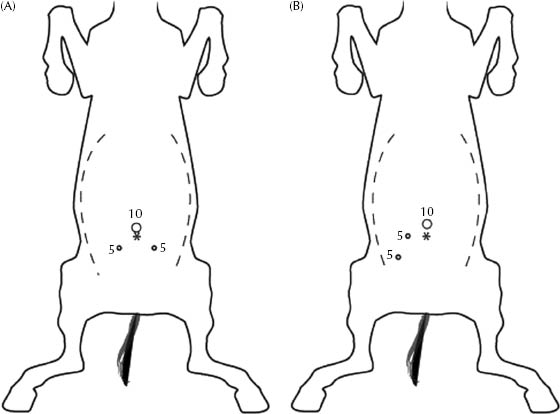

An incrementally more demanding and time-consuming technique involves intra-abdominal dissection and hemostasis, typically requiring a second instrument portal. For this technique, the telescope portal is supplemented with two instrument portals, positioned in a fashion to ensure efficient triangulation. With experience, the specific location of these portals is not critical, although for individuals with less experience, triangulation is fostered by placing an instrument portal on either side of the ventral midline approximately 15 cm cranial to the palpable cranial edge of the external inguinal ring and approximately 10–15 cm lateral to the ventral midline. Currently, the author’s preference is to place both instrument portals on the side opposite the retained testis, a practice that optimizes ergonomics and the angle of approach of the instruments to facilitate rapid dissection of the spermatic cord structures. These two popular telescope and instrument portal arrangements are shown in Figure 26.5. Regardless of the choice of portal location, it is paramount that one avoids inadvertent damage to the caudal superficial and deep epigastric vasculature. This is accomplished by planning portal locations based on the path of these vessels. In the caudal abdomen, their course can be traced by direct examination internally until they are obscured by retroperitoneal fat some distance cranial to the pelvic brim; their paths can be approximated thereafter. Another means by which the risk of accidental damage can be reduced is to avoid portal placement in the region of the lateral one-third to one-half of the rectus abdominis musculature, where these vessels and their principal branches are located (Ragle et al. 1998).

Figure 26.5 Schematic representations of instrument portal placement for laparoscopic cryptorchidectomy. (A) Conventional arrangement with an instrument portal on either side of the centrally placed telescope portal. (B) Ipsilateral placement of instrument portals. This arrangement facilitates dissection of the spermatic cord structures and is most effective when portals are placed on the side opposite the retained testicle. The asterisks represent the umbilicus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree