CHAPTER 6 CROCODILIANS

COMMON SPECIES KEPT IN CAPTIVITY

Modern-day crocodilians date back to the Mesozoic era over 65 million years ago, surviving to the present with relatively few evolutionary changes. Their biology, physiology, and anatomy are unlike those of any other reptiles. However, some species have suffered the effects of a changing environment and human encroachment; this situation has led to the formation of international programs dedicated to the preservation of threatened or near-extinct species. Of the 23 species of crocodilians, 13 can be found on the red list of endangered species.1 Taxonomic identification varies among all species, and there is debate over the proper classification of species and subspecies (Tables 6-1 and 6-2; Box 6-1). In addition to having wild crocodilian populations, countries such as Australia, India, Mexico, Papua New Guinea, South Africa, and the United States maintain intensive production operations for various species.

TABLE 6-1 Taxonomy of the Family Alligatoridae

| Common name | Scientific name | Geographic distribution |

|---|---|---|

| American alligator | Alligator mississippiensis | Southeast United States |

| Chinese alligator | Alligator sinensis | Eastern China |

| Spectacled/Common caiman | Caiman crocodilus | Central and South America |

| Broad-snouted caiman | Caiman latirostris | South America |

| Jacare caiman | Caiman yacare | South America |

| Black caiman | Melanosuchus niger | South America |

| Cuvier’s dwarf caiman | Paleosuchus palpebrosus | South America |

TABLE 6-2 Taxonomy of the Family Crocodylidae

| Common name | Scientific name | Geographic distribution |

|---|---|---|

| American crocodile | Crocodylus acutus | North, Central, and South America |

| Slender-snouted crocodile | Crocodylus cataphractus | Africa |

| Orinoco crocodile | Crocodylus intermedius | South America |

| Fresh water crocodile/Johnston’s crocodile | Crocodylus johnstoni | Australia |

| Philippine crocodile | Crocodylus mindorensis | Philippines |

| Morelet’s crocodile | Crocodylus moreletii | Central America |

| Nile crocodile | Crocodylus niloticus | Africa and Madagascar |

| New Guinea crocodile | Crocodylus novaeguineae | Papua New Guinea and Irian Java |

| Mugger crocodile/Swamp crocodile | Crocodylus palustris | Indian subcontinent |

| Saltwater/Estuarine crocodile | Crocodylus porosus | Australia and Southeast Asia |

| Cuban crocodile | Crocodylus rhombifer | Cuba |

| Siamese crocodile | Crocodylus siamensis | Southeast Asia |

| African dwarf crocodile | Osteolaemus tetraspis | Africa |

| False gharial | Tomistoma schlegelii | Southeast Asia |

BOX 6-1 Taxonomy of the Family Gavialidae

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Geographic Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Indian gharial/True gharial | Gavialis gangeticus | Indian subcontinent |

The first type of captive rearing operations consisted of alligator farming. In farming operations, breeding pairs of alligators were kept in enclosed areas where they could mate and nest (Figure 6-1). The eggs were collected from the nests and incubated. The farming operations led to ranching operations in which eggs are harvested from the wild and incubated in private facilities (Figure 6-2). The alligators hatched on an “alligator ranch” are then raised for their hide and meat. To help maintain the wild populations, 14% of the hatched alligators are eventually returned to the wild. Louisiana is the primary producer of American alligators in the world. Captive rearing operations can also be found in Florida, Texas, Georgia, and other southern states within the United States where alligators naturally inhabit. In Louisiana the majority of the operations are ranches, whereas many farms still exist in Florida. Other crocodilian species, such as the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus), are primarily raised under farming operations in other countries.

Veterinarians may also encounter crocodilians as privately kept “pets.” In the past, the spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus) and even the American alligator (A. mississippiensis) have been sold to the general public. There are many reasons why crocodilian species should not be maintained as pets. In addition to the physical dangers and risks associated with keeping crocodilians, there is the misfortune of inadequate husbandry, adversely affecting the reptile’s health. Most crocodilians grow to be larger than other reptile species and therefore have significant space requirements. Like most animals requiring an aquatic environment, crocodilians need water that is clean and free of disease. Another husbandry issue is an incorrect diet, which can lead to metabolic abnormalities and overall poor health. Many private owners are unable or unwilling to provide these conditions for their crocodilians. In addition to these issues, most states will require special permits to own theseanimals. Most people lack the proper ownership permits, and veterinarians could be liable if they treat these illegal patients. The biggest challenge that veterinarians face when treating illegally owned animals is that they are often the last chance for humane treatment for these animals. It is the duty of veterinarians to educate these clients and persuade them to place these animals in appropriate zoologic institutions or other accredited facilities.

BIOLOGY: ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

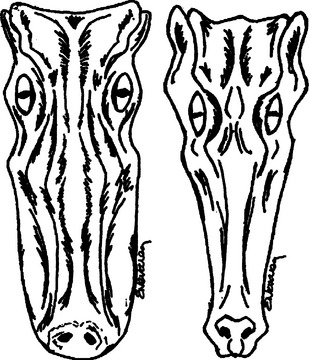

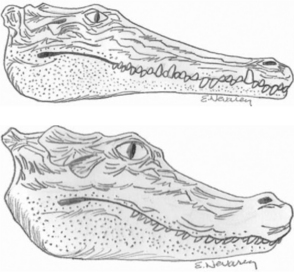

One of the most common questions a veterinarian may encounter regarding reptiles is “What is the difference between alligators and crocodiles?” The first difference is that they belong to two different families: the family Alligatoridae (see Table 6-1) includes the alligators and caimans, and the family Crocodylidae (see Table 6-2) includes all crocodiles. There is a third family, the Gavialidae (see Box 6-1), which contains the gharial, or gavial. Geographic location may help in the identification of some species. Alligators are thought to tolerate colder temperatures and live at higher latitudes, whereas crocodiles and caimans are less cold resistant and live in warmer areas.2 However, there are some anatomic features that will be most useful in differentiating alligators from crocodiles. The alligators and caimans have a broad, u-shaped snout, whereas crocodiles have a more narrow, v-shaped snout. This difference can be observed by looking at the dorsal aspect of the head (Figure 6-3). A more obvious distinction can be made when looking at their mouth from the side (Figure 6-4). Alligatorsand caimans have notches in the maxilla that fit the mandibular teeth. Therefore, they have no mandibular teeth visible if observed from the side with their mouth closed. On the other hand, crocodiles have the fourth mandibular tooth exposed when looking at them from the side with their mouth closed. Integumentary sensing organs, also known as dome pressure receptors (DPRs), are clear to gray pits present on the skin of crocodilians. Their function is not completely understood, but they may play a role as mechanoreceptors in prey detection or even as chemoreceptors aiding in detection of salinity levels.3,4 Alligators and caimans have DPRs only on the lateral aspect of the mandible (Figure 6-5), whereas crocodiles and gharials have DPRs all over the body, most noticeably on the ventral scales (Figure 6-6). The presence of DPRs can be used to differentiate the two main groups of crocodilian skins in the leather market. An additional feature that could be used for differentiation of alligators and crocodiles is the salt glands, which are absent from the tongue of alligators and caimans but well developed in crocodiles and gharials.

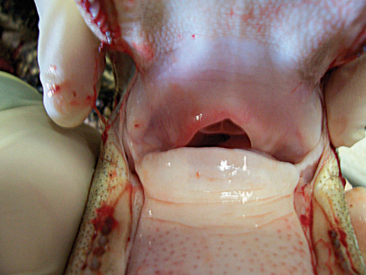

An interesting anatomic feature of crocodilians is the palatal valve, also known as the gular valve. There is some discrepancy as to the name of this structure and its two components, but I will attempt to describe them based on the anatomic location. Crocodilians have a true hard palate in the roof of the mouth that ends caudally in a soft palate. This soft palate has a ventral flap that is referred to as the velum palati. The velum palati is the dorsal component of the palatal valve, with its second and ventral component being the gular fold. This structure projects in a craniodorsal direction from the base of the tongue and has a cartilaginous base to it that is part of the larynx. Together, the velum palati and the gular fold form what is known as the palatal, or gular, valve (Figure 6-7). The function of this valve is to seal the pharyngeal cavity while under water to prevent aspiration. Crocodilians also have control of the nares and are able to open and close them as needed to prevent aspiration of water.

The cardiovascular system of crocodilians also has special characteristics. Crocodilians have a four-chambered heart as opposed to the three-chambered heart found in other reptiles and amphibians. The circulation of blood through the crocodilian heart is like that in the heart of mammals, but the crocodilians possess a viable foramen of Panizza. This opening is located at the base of the heart between the left and right aortic arches and allows for venous admixture, which is essential during periods of diving to conserve oxygen.5 During diving, there is pulmonary hypertension. This in turn creates increased pressure in the pulmonary artery and the right ventricle, which forces deoxygenated blood through the foramen of Panizza into the left side of the heart and the aorta to be distributed through the body. This mechanism allows for conservation of oxygen and supplies oxygenated blood to those organs that require it the most, allowing some crocodilian species to stay submerged for up to 6 hours.6 A second anastomosis may be present in other crocodilian species as a vessel connecting the two aortic arches.2

Submandibular (Figure 6-8) and paracloacal glands and a gall bladder are present in crocodilians. The hard dorsal scales are known as osteoderms, bony plates lined by skin. Crocodilians have a smaller gastric compartment distal to the stomach that is a gizzard-like structure in which rocks and other materials may be found. It does not appear as evolved as the ventriculus in birds, however. Crocodilian intestines have a thick wall and can have well-developed diffuse aggregates of lymphoid tissues like Peyer’s patches. There is no urinary bladder, but the colon can hold large amounts of urine and water. Sexing can be performed by palpation of the cloaca; males have a phallus that can be palpated and extracted from the cloaca. Females have a well-developed clitoris that, depending on size, can be confused with a phallus. Internally paired gonads are found near the ventral surface of the kidneys.

HUSBANDRY

Environmental Considerations

ENCLOSURE SIZE

There are no specific references for the enclosure size of crocodilian species in captivity. The size of the enclosure will largely depend on the species of reptile and the purpose of their captivity. A general understanding of biology and natural behavior of the captive species is essential to designing appropriate enclosures. Although a zoologic institution housing the species might provide more specific advice, there are some general enclosure guidelines for the commercial production of American alligators: 1 square foot per alligator up to 24 inches in length (snout to tip of tail), 3 square feet per alligator for those between 25 and 48 inches in length, and an additional square foot of space for every 6 inches in body length beyond 48 inches.7 These are the recommendations for the maximum stocking rate for alligators in commercial operations.

TEMPERATURE AND HUMIDITY

The temperature and humidity requirements for crocodilians in captivity vary with the species. Once again, an understanding of crocodilian biology and natural history is needed to try and duplicate their natural environment. An important consideration is the allowance of circadian variations in light cycle and temperatures to mimic their natural environment. This is not the case in many commercial operations, where they are maintained at a fairly constant temperature and humidity to achieve faster growth. From a health standpoint, this may allow for cross exposure of reptiles in commercial operations to infectious organisms that typically affect mammals. As the commercial reptiles are maintained at higher temperatures, new diseases commonly associated with mammals may adapt to living inside a reptile host and lead to clinical disease. In an enclosure, the temperature can be maintained via heating elements contained within the concrete slab, in line water heaters, or both. The water temperature must also be maintained during the refilling of the pen or enclosure to avoid significant temperature variations.

NUTRITION

Dietary Requirements

Crocodilians are true carnivores, as evidenced by their short gut and oral cavity. As such, they require a high protein diet, low in fiber. Their feeding habits in the wild will vary with age and food availability. Early on, their diet will con-sist of small invertebrates, amphibians, and reptiles. As they grow, they will eat larger prey of the type described earlier and will incorporate fish and birds into their dietary regime. With time, and depending on the species, size, and food availability, crocodilians will start eating mammals. There have been few studies investigating the nutritional requirements and feeding protocols of alligators.8–10 Various commercial feeds are available for alligators maintained in captivity. The commercial rations consist of dry pelleted diets that try to provide full nutritional requirements. These diets can be found with a 45%, 47%, or 56% protein content, less than 11% fat, and approximately 3% fiber content.11 Refined commercial alligator diets are widely used in production operations but may prove too expensive and/or inappropriate for the long term. A variety of whole prey feeds, such as chicken, nutria, and fish, are also recommended. If using nutria, be sure that it has not been killed using lead shot; if the lead is ingested, toxicosis can occur.12 When feeding frozen fish to crocodilians, provide a vitamin B supplement or another meat source to prevent thiamine deficiency. To prevent dietary associated problems, purchase meat from a reputable source.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Once the animal is properly restrained, a physical examination can be performed. For safety purposes, veterinarians must be aware of the location of the head and tail at all times when performing the examination. A protocol should be followed for the examination process in crocodilians as in any other species. The oral examination can be performed if a speculum (e.g., PVC pipe, piece of wood) is inserted in the mouth before securing it with tape or a rope (Figures 6-9 and 6-10). Examine the eyes for evidence of discharge and assess their function (Figure 6-11). Examine the skin for any evidence of trauma or dermatitis, and then palpate the extremities, joints, musculature of neck, pelvic region, and tail. Joint swelling is often noted with infectious disease such as mycoplasmosis or trauma. Poor body condition may be reflected in atrophy of the muscles. In commercial operations, it is important to examine the skin on the animal’s ventral aspect because this is the area where many disease manifestations will be noted. It is also common to find tooth marks, scratches, and lacerations on the ventral epithelial surface. Finally, examine the vent and cloaca for abnormalities. If working in a commercial operation, a veterinarian must examine multiple animals to determine if an observation is associated with disease. If working in a zoologic institution and any findings are suspected to be infectious in origin, other animals in the exhibit should be examined. As with any species, an examiner must know what a normal presentation is in order to recognize clinical signs of disease.

Figure 6-10 View of the pharyngeal cavity of an alligator through a PVC speculum inserted in the mouth.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Venipuncture

There are various sites for venipuncture in crocodilians. The ventral coccygeal vein can be accessed from either the ventral or the lateral aspect of the tail (Figure 6-12). This vessel lies ventral to the vertebral processes and on midline with the vertebrae. A second alternative is the supravertebral sinus, located on midline at the junction of the head and the neck (Figure 6-13). The examiner must be careful not to go too deep at this site, or physical damage may occur. A third site is an unnamed vessel located on both the left and right sides of the neck. This vessel can be approached from the dorsal aspect of the neck and is surrounded by muscles, decreasing the risk of coming in contact with nervous tissue (Figure 6-14).13 A 3-ml syringe and a 22-gauge needle are recommended for collecting blood from crocodilians. Lithium heparin and EDTA tubes are used for plasma chemistry analysis and CBCs, respectively. If collecting serum, the tubes may have to sit for at least 45 to 60 minutes before centrifugation to allow proper separation of the serum from the blood cells.

Figure 6-12 Blood draw from the ventral coccygeal vein approached from the lateral aspect of the tail in an alligator.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree