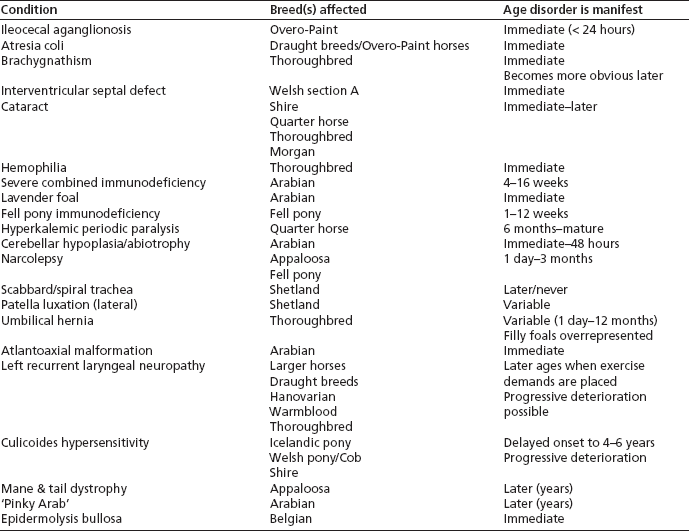

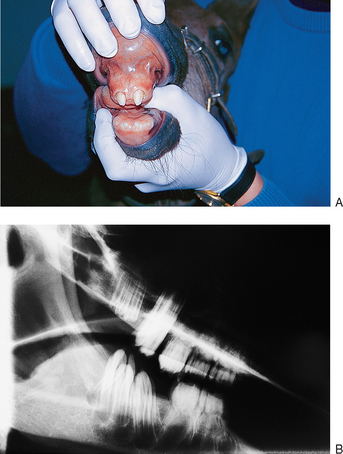

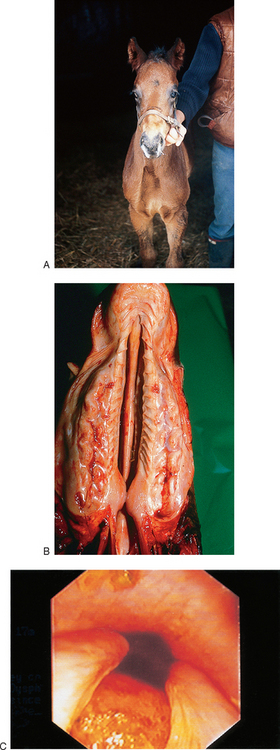

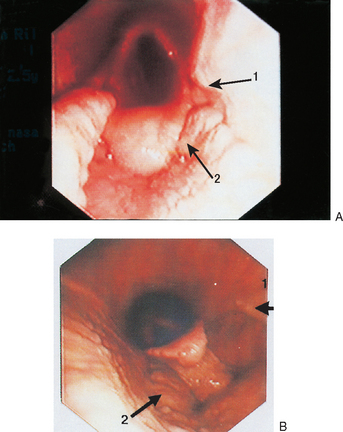

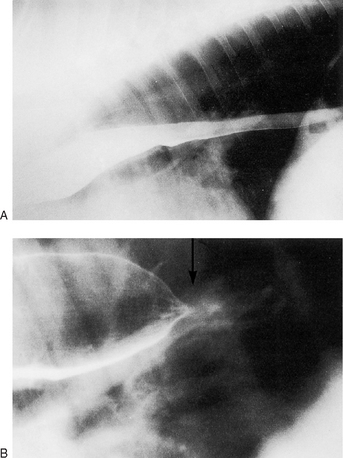

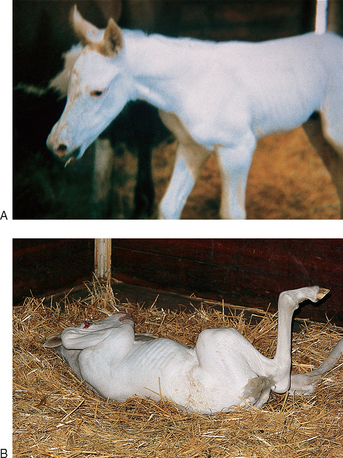

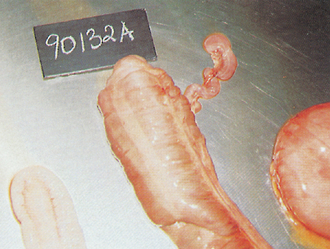

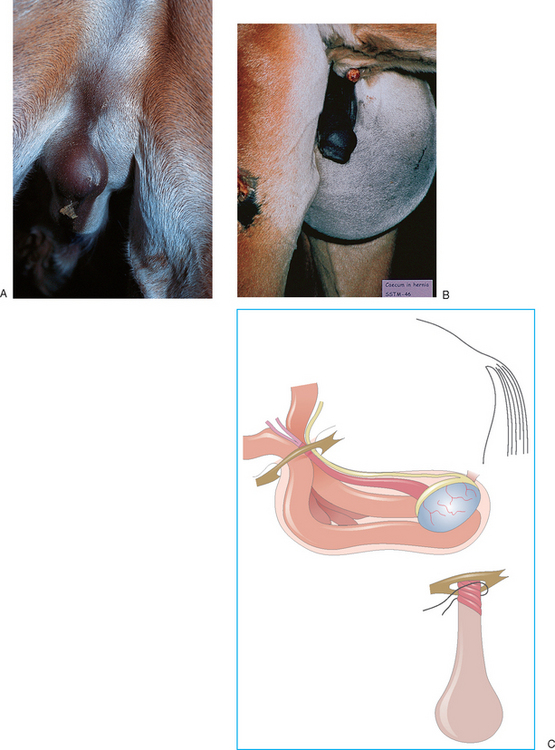

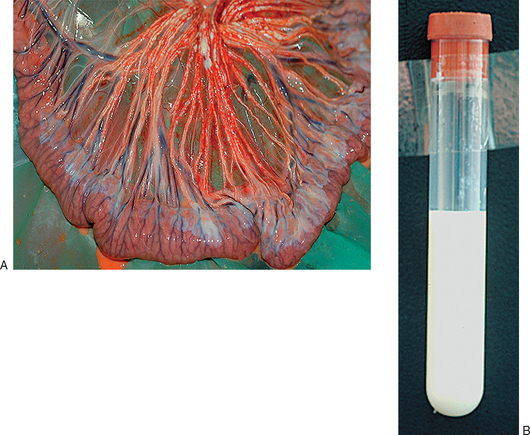

Chapter 5 Some congenital conditions have a genetic origin whereas others are due to insults, metabolic derangements and malpositioning. The cause will have a significant implication for the subsequent breeding of the mare but in many cases etiology cannot be ascertained with any confidence and a considered opinion should then be given on the likely implications. Some of the congenital diseases are sporadic events and some may be related to the maternal status. For example, foals may be born with considerable musculoskeletal problems and goiter when the dam receives excessive dietary iodine. A mare that is infected at any stage of the pregnancy has the possibility of infecting the foal. For the most part, the placental type results in considerable fetal protection but some infections such as equine herpesvirus can cross the placenta and cause considerable problems of abortion or delivery of a sick foal. Piroplasmosis (Theileria/Babesia) infections are also known to be able to cross the placenta and so this diagnosis should be considered in foals born with a very high fever, jaundice and anemia in endemic areas. Table 5.1 lists conditions that are known or thought to be inherited in horses. Dentigerous cysts (Fig. 5.1A) are a relatively common disorder that occurs as a result of an abnormal dental tissue developing on or adjacent to the side of the calvarium. They do not always have dental remnants and may be entirely soft tissue cysts with a secretory lining. Figure 5.1 (A) Dentigerous cyst (arrow); (B) X-ray of cyst showing tooth-like structure on calvarium (arrow). Dental abnormalities are relatively common in horses and may involve any of the teeth. The range of problems includes absence of one or more teeth (either the deciduous or permanent incisors or cheek teeth), maleruption (Fig. 5.2A) or supernumerary teeth (either incisor or cheek teeth but usually permanent teeth only). • chronic discharging sinus tract on the margin of the pinna with sparse glairy, oily exudate • firm, asymmetric swelling on the side of the skull Surgical removal of dentigerous cysts is described and is usually totally successful.1 The procedure is described in standard surgical texts but removal of a firmly attached large dental remnant from the calvarium can be problematical. This involves either the upper or lower jaw (maxilla/ mandible respectively) in which the incisor teeth do not meet.2 The limits of normality occur when there is any occlusion of the normal occlusal surface. The problem is usually accepted as being due to an overlong or shortened mandible. It is widely accepted as hereditary in some cases but can arise in hypothyroid foals. • Surgical correction is possible in theory but is ethically questionable in view of the suspicion that it is sometimes due to an autosomal recessive gene. However, in cases that are associated with hyperiodic hypothyroidism (goiter due to iodine excess), treatment could be contemplated. • The surgery is not simple and depends of course on the extent of the problem. Incomplete fusion of palatal shelf can affect either the hard palate or soft palate, or both.3 Hard palate clefts are rarer in foals than in other large animals while soft palate clefts are probably commoner. Defects of the palatal closure include hypoplasia of the soft palate in particular. Some cases have bilateral hypoplasia while others are unilateral. Rare cases have a mucosal fold instead of a palatal shelf. • Nasal regurgitation of milk (Fig. 5.4A). • Inability to suck if hard palate defective (possible failed passive transfer and developing sepsis). Surgery provides the only hope but is extremely difficult.4 Earlier cases have a better prognosis with surgery. There is variation in the extent and feasibility of repair.5 Short soft palate, unilateral (Fig. 5.5A) or bilateral (Fig. 5.5B) hypoplasia of the palatal shelf is rare in all species with only three known reports of the condition in the horse.6–8 Due to the complexity of the process of swallowing and the neuromuscular activity associated with it, abnormalities of the palate have serious consequences and the only option for these foals is euthanasia. Abnormal esophageal function in foals is associated with either congenital or acquired (see p. 263) conditions. Complete non-patency is not recorded but several types of esophageal strictures have been identified.9 A variety of breeds appear to be susceptible (e.g. Thoroughbred,10 Appaloosa11 and pony12). Congenital narrowing of the esophagus involving the distal third has been reported in a number of Haflinger breed horses. Persistent aortic arch with accompanying esophageal compression has also been described in foals. • Congenital abnormalities of the esophagus manifest shortly after birth usually with nasal reflux of milk – large volume regurgitation of milk out of both nostrils shortly after nursing. • Recurrent episodes of choke with nasal regurgitation of milk or sometimes saliva (or both). • Older foals may have mixtures of feed material and milk coming from nostrils. • In a few cases (e.g. esophageal web strictures) the signs may resolve spontaneously or with minimal interference. • Clinical signs and endoscopic examination of upper airway, pharynx, and esophagus will reveal narrowing with or without active inflammation. Endoscopy may reveal evidence of abnormal mucosal folds. • Ultrasonographic examination may be helpful in determining the severity and density of the strictured tissue and so give an indication of whether it was a genuine congenital web stricture or an acquired stricture. • Contrast radiography (Fig. 5.6), contrast fluoroscopy (during feeding or induced swallowing) or computed tomography may be of diagnostic assistance. Congenital web strictures (and some of the less severe) acquired strictures can be managed by progressive consistency feeding.13 However, many congenital defects are severe enough that no improvement in function occurs. Surgical treatments for thoracic-related strictures are not available, and limited success has been reported for attempts at cervical esophageal repairs.14 Bougienage using a balloon dilation procedure may be attempted in selected cases.11 Congenital ectasia of the esophagus is a rare but important condition in foals. In some cases of dilatation the problem is secondary to either a neurological ‘spasmodic’ disorder of the distal (smooth muscle) portion or to external constricting bands created by persistent vascular rings (vascular ring anomalies15). Progressive consistency feeding may be successful in some cases but postural feeding is likely to be a long-term requirement.16 This is a recently recognized congenital abnormality that is commonest in heavy horse foals (e.g. Shire). The condition appears to centre on an obstruction or discontinuity of the lacteal system in the mesentery of the small intestine. Milk feeding results in lacteal engorgement and overflow into the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 5.8B). Figure 5.8 (A) Lacteal obstruction; (B) peritoneal fluid. Note: Lacteal obstruction is a recently described condition that mainly affects heavy breeds and is characterized by mild but persistent colic. Removal of the affected lops of jejunum resulted in a cure. The peritoneal fluid was a distinctive milky white color. There is no evidence to support or refute a hereditary aspect to the condition. • Ultrasonography shows accumulation of peritoneal fluid with a higher density than other fluids. • Paracentesis shows a severely opaque milky white or slightly orange peritoneal fluid (see Fig. 5.8B). The slightly pink appearance is due to red cell leakage and lysis in the fatty fluid. The condition is virtually restricted to white foals from Overo–Paint breeding.17 This genetic defect is caused by the presence of the Ile118Lys EDNRB mutation, which is associated with a white foal usually from Overo–Overo breeding although the gene may be present in other color patterns. Some white foals do not have this mutation. • Foal is a pure white color at birth (Fig. 5.9A). A few cases have a limited faint brown/orange tinge to the ear tips and tail. • They stand and nurse normally and appear to be healthy for 1–4 hours after birth. • Within 2–24 hours affected foals begin to show colic (Fig. 5.9B), and lethargy. Then the foal usually develops an intractable, untreatable and unremitting colic that does not respond to analgesics. • Bloating with progressive abdominal distention develops. • No fecal material is passed (or is present in the rectum). • A white foal with no passage of meconium or fecal material is almost pathognomonic although not every white foal has the disease. • Non-responsive colic within a few hours of birth in a white foal of the Paint breed is pathognomonic but it is also important to consider other (possibly resolvable) causes of severe unremitting colic (see p. 237). • Clinical, radiographic and ultrasonographic evaluation points to complete bowel obstruction. Some cases have an incomplete intestinal tract also (see p. 104). Breeders of paint horses are very aware of the condition. Genetic testing to detect the defect associated with this condition can be performed on hair samples (or any other body tissues).* Hair samples for testing must be obtained by plucking (not clipping) and the results of the test will usually be known by 2–3 weeks after submission. Because the testing process takes a significant time, usually the importance of the diagnosis relates to the parents rather than the foal. This is failure of the intestine to develop full patency during embryological development. It is due to rare developmental defects that occur even less commonly in horses than in other large animals.18 The condition can be seen in any breed and this anomaly accounts for about 3% of deaths in late term fetuses and newborn foals. In horses atresia coli is the commonest of the forms. Atresia coli have membranous atresia, cord atresia with gut remnant connecting blind ends or a blind end with no connection. Most often there is a discontinuity between the left ventral and left dorsal colon. The condition is thought to be due to vascular anomalies during development.19 Atresia coli creates more dramatic signs than atresia ani. Atresia ani is the absence of normal components of the rectum and anus.20 In cases where the defect is some way forward from the anus a rectum may be present although this is effectively isolated from the more anterior intestine. • Normal birth and immediate post birth period. • With active nursing, atresia of the intestine at any point becomes apparent in the first few hours after birth. • Non-passage of meconium, straining and abdominal distention. The onset of colic depends on location of the discontinuity; signs are slower if the obstruction is distal. • Acute onset of colic with unremitting pain with progressive bloating develops from 4 to 24 hours of age. • Close examination of the anus and rectum (assuming that the anus is itself patent) will reveal no evidence of any fecal (meconium) staining. • The onset of severe unremitting pain in the total absence of any fecal staining or passage of any fecal material is probably diagnostic. • The clinical evaluation suggests large bowel obstruction with no passage of meconium and no fecal material seen with repeated enemas. Digital examination may identify defects at the terminal rectum/anus. • Radiography is helpful (particularly contrast radiography with oral or retrograde barium contrast enema studies, or both) (standing lateral) and may help to confirm the location of the problem. • Ultrasound examinations are compatible with colonic obstruction. Narrowing or absence of portions of the colon may be seen. Ultrasonographic examination can be helpful to rule out some other intestinal problems. • Exploratory laparotomy may also be required, revealing the abnormal colon. • Other causes of abdominal distention and colic (see p. 234). • Ileocolonic aganglionosis (lethal white syndrome) – this condition can coexist with atresia of the colon. • Ileus due to electrolyte or metabolic problems, sepsis or asphyxia/hypoxia syndromes and enteritis. • Strangulating intestinal obstructions (small bowel usually). • Colon torsion/colonic obstruction/impaction. • No treatment is warranted except for genuine atresia ani when the anus may be reconstructed. This particular abnormality is singularly rare in any case. • Colostomy is possible but long-term management is problematical and possibly unacceptable. • Surgical anastomosis has been attempted and is the only option. However, attempts to remove the atretic portion and anastomosis to a functional distal segment have met with few successes. • Surgical procedures are described in standard and advanced surgical texts. Surgery is sometimes impossible owing to the location of the problem. As the condition is commonly associated with more extensive intestinal motility problems, the outcome has been consistently poor and the condition is best viewed as totally fatal. The failure of surgical reanastomosis may be due to the late stages of attempted repair and to the differential sizes of bowel on either side of the defect. In addition there may be other factors relating to the motility of the intestine that may mitigate against a satisfactory outcome. Figure 5.11 Narrow pelvis syndrome: (A) foal colicking; (B) X-ray; (C) boiled-out specimen of a narrow pelvis syndrome foal showing the extreme narrowness of the pelvic canal. In this case it was impossible even to insert a narrow 5 mm probe into the meconium impaction; even in the boiled out specimen the pelvic canal will just accept a normal pencil! The ischial tuberosities are marked with a white arrow and the tuber sacrale are shown with solid arrows. Little is known of the reason for it or the possible heritability. The signs are consistent with secondary (low) meconium impaction or retention (see p. 249) and include the following: • Tenesmus (straining) may be seen within an hour or two of birth. No or little meconium is passed. • Mild but persistent colic that can progress to moderate to severe abdominal pain. • Abdominal bloating can be significant as gas build-up occurs – the abdomen becomes tympanitic (drum like). • Abdominal sounds may be increased in the early stages but become progressively less audible. High-pitched sounds consistent with a gas-filled viscus may be heard. • As the pain levels increase the foal becomes reluctant to nurse and spends much time recumbent in bizarre positions – often on its back with the legs over the head. Grunting and straining continue throughout. • Absence of any congenital physical or neurological obstruction to the intestine. • Rectal examination identifies meconium in the rectum but it may be impossible to insert even a finger through the pelvic canal. • Radiography identifies the impacted rectum and small colon and contrast studies using a barium enema will confirm the very narrow pelvic canal. The overriding aspects of therapy are to cause no further harm to the rectal mucosa and to convert the meconium into a soft liquid. The former is achieved through minimal interference. The latter is reliant on an effective enema and breakdown of the hard pellets of meconium. Oral doses of liquid paraffin (mineral oil) are not effective in resolving the condition. Triple phosphate and soap-and-water enemas are used but are very slow and seldom cause enough liquefaction of the meconium. The best way to treat the condition is to use an acetylcysteine enema (see p. 250). The procedure is highly effective and this procedure should be used wherever congenital narrowing of the pelvic inlet is confirmed or is suspected. Scrotal hernias are relatively common in newborn foals, particularly those of heavy breeds (Shire horses, etc.). Certain breed associations regard the conditions as unacceptable inherited characteristics but many foals are born with them and they resolve spontaneously over the first days of life. There is strong evidence to suggest that congenital inguinal hernia is inherited. Inguinal hernia is commoner in male foals but females can be affected. There is some debate about increased relative size of the inguinal canal but little evidence to support this. In some very young foals the intestine is in the inguinal canal or scrotum before the testis migrates into the scrotum. Both these hernias may also be acquired due to trauma. • Reducible swellings at the umbilicus. • The contents can be shown to be intestine, fat or omentum by ultrasonography. • Non-strangulating and non-obstructive hernias have little implication. • Strangulating lesions result in severe non-responsive colic.

CONGENITAL ABNORMALITIES AND INHERITED DISORDERS

INTRODUCTION

ALIMENTARY SYSTEM

DENTAL CYSTS AND DENTAL ABNORMALITIES

Etiology

Clinical signs

Treatment

OVER/UNDERSHOT JAW (SUPERIOR/INFERIOR BRACHYGNATHISM)

Etiology

Treatment

CLEFT PALATE (Fig. 5.4)

Etiology

Clinical signs

Treatment

HYPOPLASIA OF THE PALATAL SHELF

ESOPHAGEAL STRICTURE

Etiology

Clinical signs

Diagnosis

Treatment

ESOPHAGEAL DILATION/MEGAESOPHAGUS (Fig. 5.7)

Etiology

Treatment

CONGENITAL LACTEAL OBSTRUCTION (Fig. 5.8)

Etiology

Diagnosis

ILEOCOLONIC AGANGLIONOSIS (LETHAL WHITE SYNDROME)

Etiology

Clinical signs

Diagnosis

Control/prevention

NON-PATENT INTESTINAL DISORDERS – ATRESIA COLI/RECTI/ANI

Etiology

Clinical signs

Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis

Treatment

COLT FOAL NARROW PELVIS SYNDROME (Fig. 5.11)

Etiology

Clinical signs

Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis

Treatment

HERNIA

Etiology

Scrotal/inguinal hernias (Fig. 5.14)

Clinical signs

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree