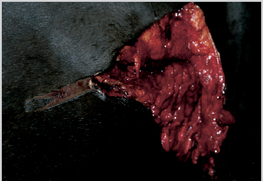

9 Wounds that are correctly examined and treated at an early stage have a much higher chance of healing quickly and with minimal complications. Wounds that are neglected or managed badly, regardless of their severity or otherwise, will inevitably heal poorly, slowly, and with more extensive scarring. The rate and efficiency of wound healing largely depends upon factors such as site, complications, inhibitors of healing, time between wounding and treatment, and the type of treatment applied. Recent research has confirmed that certain areas on the horse heal better than others, and that ponies tend to heal better than horses1. Body wounds on horses and ponies usually heal remarkably well with a high element of contraction, and leave scars that are much smaller than the original wound. Limb wounds on large horses heal notoriously badly and tend to heal by epithelialization and scars may be larger than the original wound. The worst region for healing is the distal limb region (both fore and hind) of horses over 145 cm. Limb wounds of ponies (<145 cm) heal as well as wounds on the trunk of larger horses and healing is particularly impressive on the trunk of ponies12. The presence or absence of factors that inhibit or retard healing will affect scarring (see p. 25). Early physiologically sound treatment provides the best chance of healing (even for difficult or complicated wounds). Neglected/long-standing (chronic) wounds become progressively less likely to heal with passing time. Skin injuries with skin deficits and/or ‘degloving’ are relatively common (Figures 72, 73), and management of these injuries can be very difficult. The absence of ‘spare’ (loose) skin on limbs means that large deficits in these sites require particular care. Notwithstanding the best possible care, healing is likely to be prolonged. Figure 72 Extensive skin lacerations with skin deficits from a road traffic accident. The injury healed well by second intention, although initially the skin was sutured where possible to reduce the healing time. Figure 73 A severe degloving injury of the forearm. Walking sutures and drains were used to restore the skin approximately to normal position, but the wound broke down extensively and took some months to heal by second intention. (Courtesy of RR Pascoe.) Carefully placed subcutaneous ‘walking sutures’ limit dead space by firmly fixing the skin to the deeper structures, but this may not always be possible. This minimizes tension on any single part of the incision; with careful extension of the skin it may be possible to eliminate tension on the wound line. If the injury is more than 1–2 hours old, the skin will have shrunk significantly, and it may be difficult to restore it to its natural position. The skin wound is closed using interrupted horizontal or vertical mattress sutures with monofilament nylon (4 or 5 metric/1 or 2 USP). Tension across the wound site can be relieved by supported quill sutures. These wounds involve the upper limb or body trunk regions (Figure 74). Wounds involving muscle damage sometimes bleed quite heavily – this is particularly so if the muscle is lacerated (as opposed to bruised or crushed). Figure 74 A deep laceration with muscle involvement. The wound was repaired in three layers and healed by primary union. At this stage it may not be possible to decide which tissue is viable. Many extensive wounds that are left to heal by second intention heal largely by contraction. Cosmetic results tend to be good with a significantly smaller scar than the wound (see p. 17). Primary closure of the muscle deficits may shorten the recovery period and improve functional restoration. Fresh injuries are far more amenable to primary closure. The location of the wound is important because muscle damage may be more important over the eyes or on the face than on major muscle masses. Adequate restraint should be used to permit close examination, which may require sedation with an α-2-agonist (e.g. romifidine, detomidine, xylazine) (see p. 39). Hemorrhage should be controlled (see p. 39), and appropriate anesthesia (regional blocks or local inverted L block) is required for exploration, cleaning, and possible suturing. Local anesthetic infiltration into the wound itself is not conducive to healing, and should be avoided if possible by using regional blocks. In particular, anesthetic with adrenaline should not be used. The wound should immediately be covered with a hydrogel and the margins of the wound carefully clipped or shaven to establish the full extent of the injury, and in particular the full extent of the underlying muscle damage. The skin flap and the underlying muscles should be handled gently and washed carefully with warm saline. Chemical antiseptics should be avoided as far as possible unless there is gross contamination. Antibiotic powders (such as crystalline penicillin and aureomycin powder) may be cytotoxic and therefore retard healing. If the wound is infected or is likely to be infected then such an approach may be helpful, i.e. the benefit outweighs the disadvantages. The wound should be irrigated with copious warm (body temperature) sterile saline (as much as the horse will allow) to remove superficial contamination and the residues of the hydrogel. Further applications of hydrogel to the wound site will keep the surface moist and protected against further bacterial contamination. Not all wounds extend perpendicularly into the deeper structures and so the skin wound may not directly overlie a joint (Figure 75). Deficits of the joint capsule are a serious complication (Figure 76). Some injuries involving joints or tendons are complicated by fractures. Injuries involving the flexor tendons during full limb extension (i.e. the tendon is at full tension) cause severe damage (or even total disruption). The skin injury may appear to be relatively trivial (Figure 77). Furthermore, the tendon injury may be at a site that is quite a distance from the skin injury. The exact location and extent of the wound should be established. Figure 75 The lateral pouch of the elbow joint is frequently well away from the apparent site of the elbow itself. This small wound gave no real indication of the severity of the problem. Figure 76 Severe abrasion of the fetlock joint from a trailer injury. Although the injury is particularly severe with extensive tissue loss, immediate treatment resulted in a surprisingly satisfactory repair after some months. Figure 77 An over-reach injury in a racehorse. The location of the injury suggests that the digital sheath was involved. With emergency treatment the wound healed without complication. Close observation of the posture of the foot and fetlock when the horse is made to take weight on the leg will help to identify tendon disruption. The cause of the wound is a useful factor in deciding on the likely treatment. Sharp lacerations are usually easier to repair than those complicated by extensive tissue bruising and widespread damage to adjacent structures. If the patient cannot move or is unwilling to move there may be concurrent damage to other structures (joints/bones). The horse should not be moved (an ambulance or trailer may be helpful) as movement can exacerbate a tendon or joint injury and may also cause displacement of fractures. It can also result in dissemination of infection. Significant bleeding is unusual. Exposure of bone occurs most often on the distal limb and the face/head (Figure 78). Sequestrum formation occurs when there are fragments of non-viable bone, the periosteum is stripped from the bone, or the periosteum is dried/desiccated. The blood supply to the bone is disrupted, and the outer one-third of the cortex becomes necrotic because it derives its blood supply from the periosteum. Sequestrum formation also occurs when the exposed surface of the bone is infected. Figure 78 A wire laceration on the forearm in which periosteum was exposed and damaged. The areas of denuded bone formed a sequestrum over the following 12 weeks. Healing was delayed until the necrotic bone had been removed. Sequestrum can usually be identified radiographically provided the beam is angled appropriately. Sequestration is not an inevitable consequence of periosteal injury, but is a common feature of those wounds that involve periosteal damage that fail to heal. Grafts will not take on denuded bone.

Complicated Wounds

. Skin Lacerations with Skin Deficits or Degloving

. Skin Lacerations with Skin Deficits or Degloving

. Wounds Involving Muscle Damage

. Wounds Involving Muscle Damage

. Wounds Involving Synovial Structures

. Wounds Involving Synovial Structures

. Wounds Involving the Mouth, Tongue and Jaws

. Wounds Involving the Mouth, Tongue and Jaws

. Wounds Involving Nerve Damage

. Wounds Involving Nerve Damage

. Wounds Involving Cranial Damage

. Wounds Involving Cranial Damage

. Wounds Involving Hoof Capsule and Coronary Band

. Wounds Involving Hoof Capsule and Coronary Band

. Wounds Involving Open Body Cavities

. Wounds Involving Open Body Cavities

Skin Lacerations with Deficits of Degloving

Introduction

Surgical Procedure

Wounds Involving Muscle Damage

Introduction

Preliminary Approach

Wounds Involving Synovial Structures

Introduction

Wounds with Exposed Bone

Introduction

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

. Wounds with Exposed bone

. Wounds with Exposed bone . Eyelid Injuries

. Eyelid Injuries . Eye Injuries

. Eye Injuries . Wounds Involving Major Blood Vessels

. Wounds Involving Major Blood Vessels