CHAPTER 51 Coccidioidomycosis

Coccidioidomycosis is an infectious disease caused by the mold/fungus Coccidioides immitis. (Recently, a second species, Coccidioides posadasii, has been proposed for the genus.1) C. immitis resides in the soil and causes disease in mammalian hosts after being inhaled or rarely through transcutaneous introduction.

Many animal species have been infected with C. immitis, including many equids (Boxes 51-1 and 51-2). Because human patients have more clinically recognized coccidioidal infections than other species, much of the knowledge about the disease derives from infections of Homo sapiens.

Box 51-1 Equids with Naturally Acquired Coccidioidomycosis

Horse, domestic (Equus caballus)

Horse, Przewalski’s (Equus przewalski)

Onager (Equus hemionus onager)

Box 51-2 Animal Species with Naturally Acquired Coccidioidomycosis

This compilation includes cases detected by Raymond Reed, DVM, and Kathryn Orr, DVM; data also from various publications.

The first reported case of coccidioidomycosis was described in a person in Argentina by Posadas2 in 1892. In 1894, Rixford3 reported a human case in California, the forerunner of thousands of additional cases occurring in the southwestern United States. Both Posadas and Rixford carried out experiments involving injection of C. immitis into experimental animals (not including equids).

Naturally occurring coccidioidomycosis in nonhuman mammals was reported in cattle by Giltner4 in 1918. The disease was not reported in equids until the 1940s, according to Maddy.5 Wilding et al.6 alluded to the disease in burros. The earliest infections recognized in horses included those reported by Maddy. Thirteen of 22 horses raised near Phoenix and a burro near Mesa, Arizona, were reactive to intracutaneously injected coccidioidin, indicating prior infection with C. immitis.

Deliberate infection of horses by intravenous injection of live C. immitis was carried out by Smith et al.7 to induce antibodies that could serve as standardized serologic controls (particularly for the diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis in humans). Neither the size of the inoculum (i.e., how many viable C. immitis cells were injected) nor the clinical outcome was described, although serum from these horses was satisfactory as an antibody-positive serologic control. Cases of equine coccidioidomycosis were reported by Zontine,8 Rehkemper,9 and Crane.10

ETIOLOGY

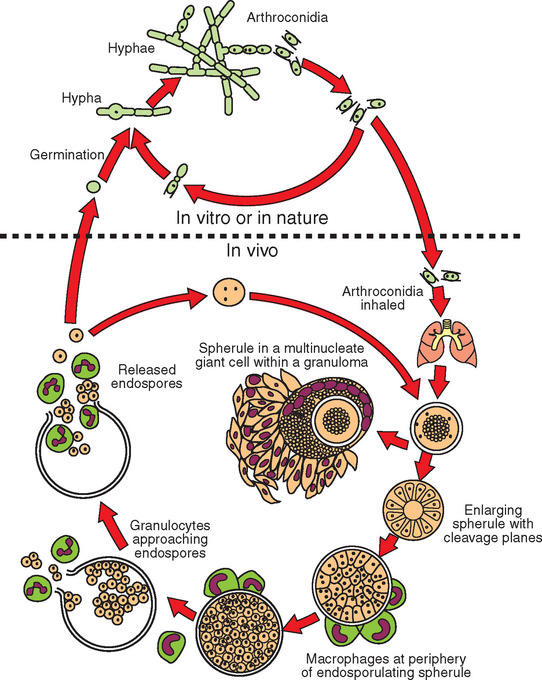

Coccidioides immitis is a mold/fungus that is diphasic and pleomorphic; its (saprobic) growth phase in nature or in usual laboratory culture differs morphologically from the (parasitic) growth phase usually seen in the tissues of an infected host (Fig. 51-1). The saprobic form consists of filaments (hyphae) 2 to 3 μm in diameter, some of which can differentiate into a chain of thick-walled arthroconidia (“spores”). These conidia can be barrel shaped or cylindrical, 2 × 5 μm in size, and often alternate with empty, degenerate “disjunctor” cells that readily fracture, permitting airborne dispersion of the arthroconidia.

Fig. 51-1 Life cycle of Coccidioides immitis.

(Modified from Collier L, et al, editors: Topley & Wilson’s microbiology and microbial infections, ed 9, London, 1998, Hodder Arnold.)

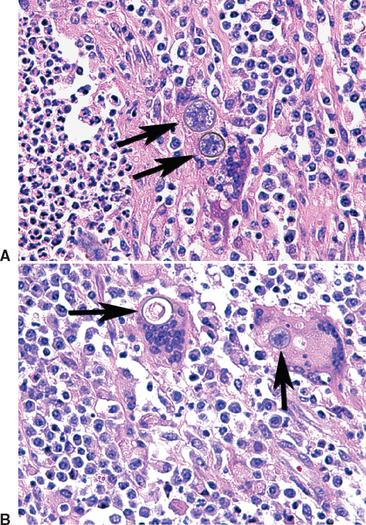

When inhaled or otherwise introduced into the tissue of a mammalian host, the arthroconidia become rounded and enlarge to become spherules (20-100 μm in diameter), which undergo internal division of cytoplasm and nucleus. This results in the production from a single cell (arthroconidium) of hundreds of endospores in one generation. Each released endospore can then enlarge to become a spherule, which releases more endospores. The conversion from arthroconidia to spherules is influenced by elevated (body) temperature, increased carbon dioxide (CO2) and perhaps surface-active agents; in vivo the process appears to be influenced by presence of inflammatory leukocytes (Fig. 51-2). The released endospores evoke a polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) response, whereas the spherules evoke a macrophage response. Thus, mixed suppurative-granulomatous inflammation is characteristic of coccidioidal lesions. In chronic lesions, caseation and hyalinization (fibrosis and collagen deposition) are seen.11

The wall of C. immitis contains the polysaccharides chitin, glucan, and mannosyl (proteins);12 these impart toughness to the exterior. During the growth of the spherule-endospore phase, enzymes such as chitinase, glucanase, and proteases likely participate in changing the cellular structure during the morphologic changes. With the maturation of the spherule and its release of endospores, chitinase is released.13 This enzyme is the antigen to which the infected host responds by production of immunoglobulin G (IgG, complement-fixing antibody).14

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND EPIZOOTIOLOGY

Coccidioides immitis resides in soils of the Western Hemisphere. The areas affected extend from 40 degrees south latitude (Argentina) to 40 degrees north latitude (California, Northeastern Utah) (Fig. 51-3). Thus, areas of South, Central, and North America harbor C. immitis. The fungus is indigenous to California, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, and adjacent areas of Mexico.15

Fig. 51-3 Geographic distribution of Coccidioides immitis sites where coccidioidomycosis is usually acquired.

(Modified from Pappagianis D. In Stevens D, editor: Coccidioidomycosis, New York, 1980, Plenum.)

Persistence of this fungus in the soil and arrival of previously uninfected individuals (human and nonhuman) ensure continued occurrence of coccidioidomycosis. Many, but not all, of the areas to which the organism is endemic correspond to the Lower Sonoran Life Zone, characterized by hot, dry summers, relatively mild winters, and moderate rainfall. The number of cases of coccidioidomycosis is influenced by rainfall in at least two ways: (1) rainfall wetting the soil can reduce dust and airborne arthroconidia, suppressing the number of infections, or (2) rainfall, by moistening the soil, can lead to growth of the hyphal/arthroconidial form, increasing the subsequent risk of exposure to infectious arthroconidia and therefore more cases. In the late summer and in the fall, there is usually a progressive increase in the number of cases until the rainy season begins. In Arizona, a dry period is followed by summer “monsoon” rains, then followed by another dry season, resulting in essentially two annual seasons of coccidioidomycosis.

Coccidioides immitis does not appear uniformly distributed throughout endemic areas; rather, it exists in scattered pockets of soil. The characteristics of the soils have not provided a specific, clear reason for the restricted distribution and persistence of the organism. The soil often is alkaline, may contain ash from the ancient campsites of Native American Indians, and often contains concentrations of certain salts, such as calcium, sulfate, and sodium chloride, which can inhibit microorganisms that can compete with (or inhibit) Coccidioides. These competing organisms probably decrease as the soil water evaporates, increasing the concentrations of salt but still permitting survival of Coccidioides.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree