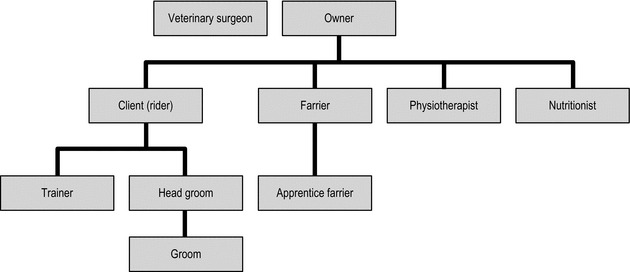

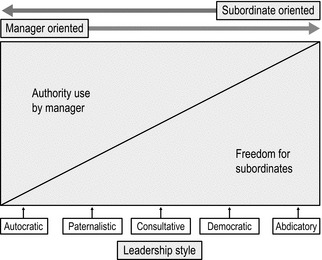

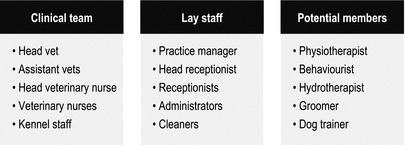

3 After reading this chapter, students will be able to: • Understand the nature of clinical leadership and its application to all stages of veterinary careers. • Explain the difference between leadership and management. • Describe the members of the veterinary practice team and discuss their different roles. • Describe the components of clinical governance and understand their application in the veterinary context towards the attainment of quality in clinical care. The term ‘professionalism’ – the attitudes and behaviours necessary to be an effective member of a profession – is frequently discussed in the medical context but is becoming a more important topic for veterinary surgeons, as the profession considers its role in society. This is especially true when considering global public health, in which veterinary surgeons should play a prominent leadership role (Wagner and Brown, 2002). Veterinary leaders need to demonstrate professionalism, and ‘leadership’ is often included as an element of professionalism. There is a clear overlap between these two concepts, meaning that the development of professional skills should also improve leadership abilities. Leadership can be broken down into three simple components (Davidson et al., 2006): • identifying a goal or target; • motivating other people to act; • providing support and motivation to achieve mutually negotiated goals. Importantly, clinical leaders maintain some form of clinical role, and work in a collaborative style with other health professions and non-clinical leaders to achieve improvements in clinical care (Edmonstone, 2009). Their focus is on the patient or service provided, rather than on the organization itself, which tends to be the role of healthcare managers; in the veterinary context, this is the practice manager. As Treasure (2001) is keen to point out, however, leadership can be mistaken for ‘being in charge’, particularly by medical consultants who may be in charge of a team, without considering that they are part of a service and care network. This could also be true in veterinary practice, where a leader is often the owner of the practice and seen to deliver orders rather than actually lead a multidisciplinary team effectively. It must also be remembered that leaders are even better placed to exert power and influence, and so these abilities must be used carefully so that privileges are not abused (Anderson, 2011). The personal power of clinical leaders could be much greater than that of non-clinical leaders, because of their perceived credibility by fellow professionals (Edmonstone, 2009). Professionalism and leadership could, therefore, be seen as intrinsic to each other; indeed, within the veterinary profession, there is more of a tendency to discuss the latter. 1. A non-clinical manager is employed to oversee the day-to-day running of the practice and manage human resources. The practice manager in this situation is the employee of the individual who owns the practice, and varying amounts of autonomy are given, with the owner ultimately retaining the leadership role. 2. A veterinary surgeon (likely to be the practice owner) may manage the practice, and also have a clinical leadership role during client- and patient-facing activities. 3. In the corporate-owned practice, veterinary surgeons may lead and manage clinical activities but leave non-clinical management jobs to a central management team. Veterinary surgeons are more commonly becoming part of this central team, for example as regional operations managers within a corporate structure. The differences between leadership and management are debated extensively in the literature, with some resistance to definitions which categorize them as distinct entities, often citing management as systems and process based, and forgetting that leaders also ‘must ensure that systems, processes and resources are in place’ (Long, 2011). It is certainly true that a badly managed practice may also suffer from poor leadership, and vice versa, but ultimately whichever role a veterinary surgeon adopts there will be similar skill sets, which need to be developed in order to influence a successful team approach to patient care. The small size of many veterinary teams means that individuals often take on different roles, many of which require leadership skills. There is some discussion around the ethical nature of leadership and management, with the implication that leadership is more ethical than managership, because of the tendency of the latter to be more ‘dictatorial’ in style (Ross, 1991). Whether or not this is true, it is worth considering that leadership may be a more realistic approach in the ethical minefield that is the veterinary practice. Table 3.1 illustrates the different characteristics required for management and leadership. Veterinary surgeons are likely to need to develop characteristics from both the management and leadership list as they perform a dual role in many situations. Table 3.1 The different characteristics of management and leadership Source: Long (2011, p. 4). It is thought that clinical leaders are more likely to take evidence-based, reflective views on healthcare, and that this may be in conflict with the scientific–bureaucratic model promoted by non-clinical managers (Davies and Harrison, 2003). This can lead to ethical dilemmas for the practising veterinary surgeon, who is trying to balance clinical leadership skills aimed at improving patient care and animal welfare with the need to manage a practice and make a profit. Equally, there is potential for practice managers to come into conflict with veterinary surgeons employed as assistants who are more junior clinical leaders. These individuals will need to develop their leadership skill set in order to convince a more bureaucratic manager of their actions, which may be more patient centred than practice centred. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of both to ensure the culture of the practice is effective, and to develop a good working relationship allowing everyone to work as a cohesive team. The veterinary profession has undergone a considerable number of changes over the last two decades. The changing nature of animal ownership and farming practices has increased the numbers of specialized small, large and equine animal practices, and reduced the number of traditional mixed practices, which are usually run by one or more partners. Practices are now commonly owned by shareholders within a corporate management structure, and ownership by limited company is common even in the more traditional partner-led organizations. This has meant a readjustment in management and leadership of these practices. Practice managers are often now a part of this environment, along with numerous other professionals and paraprofessionals working alongside the veterinary surgeons (Figure 3.1). Some larger practices have embraced these changes fully and now employ professionals other than veterinary surgeons and nurses, with the aim of developing a wider scope for offering different services to clients and patients. Other practices have maintained a more traditional veterinary team, and communicate with other professionals contributing to patient care as and when required. Figure 3.1 • An example of different team members in a small-animal practice. To an effective clinical leader, both types of team can be challenging. The veterinary surgeon may assume that everyone working in the team is aiming for the same ultimate outcome of excellence in patient care. However, tensions can develop when this is not the case, and communication and negotiation are of the utmost importance. The first step is to actually take on the responsibility of ‘leader’, which may not be a role every veterinary surgeon feels inclined to adopt, and some veterinarians may even leave leadership to the client. However, once the responsibility is identified, the second step is to decide how best to lead this complex team, and develop the skills and behaviours necessary to do so. This is required of even the most junior assistant. The different teams illustrated in Figure 3.1 must interact and communicate effectively. Leadership from veterinary surgeons is therefore essential. In the situation illustrated in Figure 3.2, which depicts a more complex team, the vet may come under the direction of both owner and client, or these may be the same person. Leadership skills are very important if such a team is to function effectively, and the vet is ideally situated to lead this team. Social scientists, business theorists and psychologists have spent several decades studying effective leaders and their followers, and trying to establish the behaviours and skills necessary to develop a successful team. The classic leadership model first published in the 1950s (Tannenbaum and Schmidt, 1958), as shown in Figure 3.3, demonstrates a scale of influence during decision-making processes by leaders and their subordinates. This scale ranges from complete control by leaders through to total autonomy of subordinates. It is interesting to examine the behaviours described and consider leaders who feature prominently in the media. Politicians are a good example, but where on this scale do these leaders sit?

Clinical leadership and professionalism in veterinary practice

LEARNING OUTCOMES

Introduction

What is clinical leadership?

Leadership and management

Aspect

Management

Leadership

Style

Transactional

Transformational

Power base

Authoritarian

Charismatic

Perspective

Short-term

Long-term

Response

Reactive

Proactive

Environment

Stability

Change

Objectives

Managing workload

Leading people

Requirements

Subordinates

Followers

Motivates through

Offering incentives

Inspiration

Needs

Objectives

Vision

Administration

Plans detail

Sets direction

Decision-making

Makes decisions

Facilitates change

Desires

Results

Achievement/excellence

Risk management

Risk avoidance

Risk taking

Control

Makes rules

Breaks rules

Conflict management

Avoidance

Uses

Opportunism

Same direction

New direction

Outcomes

Takes credit

Gives credit

Blame management

Attributes blame

Takes blame

Concerned with

Being right

What is right

Motivation

Financial

Desire for excellence

Achievement

Meets targets

Finds new targets

The complex nature of the veterinary team

Liz Mossop retains copyright to her original illustration.

Leadership styles

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine