CHAPTER 99 Clinical Examination of Female Reproductive Organs

Detailed examination of records, with or without the assistance of computer programs, often identifies deficiencies in breeding herd performance. The computerized record systems and implementation of statistical process control (SPC) methodology are excellent tools to characterize, at least numerically, specific areas that require long-term or immediate attention. Despite the use of new technology and analytic procedures, swine practitioners often are required to provide accurate diagnoses of noninfectious reproductive failure or urogenital infections in female swine and to identify shortcomings in reproductive performance. Because sow and gilt reproductive organs are easily evaluated at slaughter, this diagnostic technique represents minimal cost to the producer yet provides accurate assessments of the precise causes of reproductive failure.

POTENTIAL USES

Clinical examination of reproductive organs is useful to confirm infectious and noninfectious causes of reproductive failure (Box 99-1). Presence of physiologic or anatomic abnormalities associated with reproductive failure can be verified or refuted by examination of the female genital organs. Alternately, findings on these examinations may clearly illustrate shortcomings in breeding management.

Box 99-1 Examination of the Reproductive Tract of Female Pigs: Clinical Applications

Noninfectious Causes of Reproductive Failure

Failure to return to estrus after weaning (anestrous sows)

Regular returns to estrus after mating

Irregular returns to estrus after mating

Pseudopregnancies and not-in-pig sows

Infectious Causes of Reproductive Failure

Collection of fetuses and uteri from affected sows before parturition, e.g., PRRSV

Collection of fresh tissue, fetal blood, or thoracic fluid for submission to diagnostic laboratories

Evaluation of reproductive and urinary tracts for evaluation of urogenital infections

SPECIMEN COLLECTION TECHNIQUES

Procedures at the Slaughterhouse

Reproductive and urinary tracts are examined at the slaughterhouse or removed to a clinic or laboratory with appropriate approval from regulatory officials. Individual identification of animals at slaughter is used to correlate gross and histologic findings with the reproductive history of the sow. Ear tags are convenient, but ear, shoulder, or flank tattoos constitute a more reliable means of identification.

Initial Procedures and Gross Examination

Gross lesions are noted on examination of the ovaries, oviduct, uterus, cervix, vagina, urinary bladder, and kidneys. If an infectious etiology is suspected, culture swabs are procured using aseptic technique from both horns of the uterus, urinary bladder, and kidneys. Failure to use aseptic technique usually results in gross contamination of the swabs and erroneous culture results. Urine is obtained by centesis with 20-gauge needles and stored on ice (5° C) for transport to the laboratory. Storage of urine for more than 12 hours limits the diagnostic value of the specimen.1 Owing to the broad spectrum of bacterial agents involved in urogenital infections,2 swabs are submitted for culture under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Determination of bacterial sensitivities to antibiotics also should be requested for future reference.

NORMAL MORPHOLOLGY

Normal Ovarian Structures

Follicle Growth and Ovulation

Ovarian follicles destined for ovulation grow from approximately 4 to 5 mm in diameter on day 15 (day 0 = the first day of standing estrus) of the estrous cycle to an ovulatory diameter of 8 to 12 mm (Fig. 99-1). Preovulatory follicles have taut, almost transparent walls and contain straw-colored fluid. Estrogen (17β-estradiol), the predominant ovarian hormone produced at this time, contributes to estrous behavior and to morphologic changes in the reproductive tract and triggers the surge of luteinizing hormone (LH) from the anterior pituitary gland.

Luteal Structures

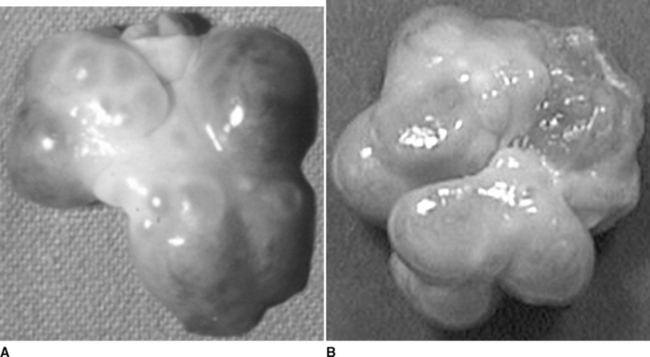

After ovulation, collapsed follicles are 4 to 5 mm in diameter. Blood rapidly fills the central cavity of the follicles. At this stage, these blood-filled structures are considered corpora hemorrhagica. Luteinization of the follicular remnants results in the formation of multiple corpora lutea. By day 5 to 6, each corpus luteum (CL) has reached its mature diameter of 9 to 11 mm, and the central cavities are completely replaced by luteal tissue (Fig. 99-2). The corpora lutea produce the steroid hormone progesterone. Serum progesterone concentrations, detectable within 1 to 3 days after estrus, increase until a maximum is achieved during mid- to late diestrus.

Degeneration of the corpora lutea commences at approximately day 13 to 15, coinciding with increased concentrations of the luteolysin prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α)3 and decreasing concentrations of progesterone. It is assumed that PGF2α contributes to regression of the corpora lutea; however, other factors evidently influence the structural regression of the corpora lutea. Obvious indications of CL regression are the change in color from reddish-pink to yellow and a gradual decrease in diameter. A new wave of follicular recruitment commences on days 13 to 15, with follicle enlargement and hyperemia obvious by day 17 (Fig. 99-3). Follicles continue to enlarge concomitant with regression of the corpora lutea.

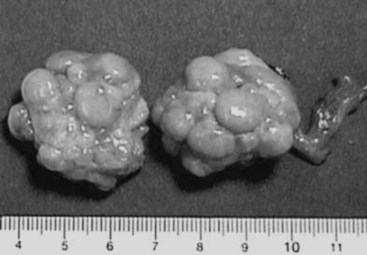

With maternal recognition of pregnancy (occurring on days 10 to 14 after ovulation and successful mating),4 CL lifespan is extended throughout pregnancy. The gross appearance of the corpora lutea of pregnancy (Fig. 99-4) is remarkably similar to that of the corpora lutea during diestrus. Dissection of the uterus will reveal fetuses if the animal’s pregnancy had progressed to 20 days of gestation or later. Before 20 days of gestation, it is useful to flush both horns of the uterus to detect the presence of early embryos. Confirmation of pregnancy status is particularly applicable when the quality of matings or estrus detection requires scrutiny or when records of these events are not maintained in an orderly and detailed fashion. It is not uncommon to observe pregnancies in animals that were erroneously recorded as anestrous. These observations illustrate weaknesses either in the record system or in management practices.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree