Suffering due to frustration may be caused by owners preventing animals performing motivated behaviours. Animals can be highly motivated to perform many normal or natural behaviours, and also many learned ones, and have general psychological needs such as choice, control and exercise. Conspecific interaction (with members of their own species) is important for members of gregarious species, such as sheep, pigs, chickens, cows, dogs, rabbits and horses, although many are kept in visual or tactile isolation. Human interaction is important for some individuals, such as dogs (Tuber et al. 1999; Odendaal 2000; Hennessy et al. 2002; Kobelt et al. 2003; Hiby et al. 2004; Coppola et al. 2006; Lefebvre et al. 2007), although many dogs are frequently left alone for long periods (PDSA 2011).

Owners sometimes also euthanase their animals prematurely, abandon them or relinquish them to shelters (Figure 2.1). Rescue shelters are a valuable way to give companion animals (and less commonly wild and farm animals) a second chance and to decrease abandonment. However, financial limitations can mean that animals’ lives are compromised to varying degrees, despite the carer’s best intentions (Tuber et al. 1999; Hennessy et al. 1997). In extreme cases, welfare problems can mean some animals would be better off euthanased than not provided with adequate veterinary care, kept in overcrowded kennels with insufficient enrichment or kept beyond the time at which they should be euthanased (especially for wild animals who could not survive in the wild or farm animals that live beyond their natural lifespans). In less extreme cases, welfare compromises can decrease carers’ ability to rehabilitate and train animals while also making it good for animals to be rehomed as quickly as possible.

Figure 2.2 Owners may harm their animals by failing to provide enough resources. (Courtesy of RSPCA Bristol.)

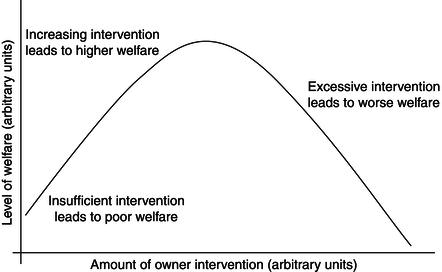

Owners cause problems through their behaviours. Sometimes these behaviours are deliberate actions. Sometimes they are accidental. Sometimes owners neglectfully fail to act, and thereby to provide things that avoid welfare problems, while also preventing other people or the animal itself from doing so, such as when they underfeed an animal (Figure 2.2). As well as under-provision, owners cause harms by excessive provision (Figure 2.3), such as when they overfeed an animal (Figure 2.4). These distinctions are important in identifying win-win situations where improving animal welfare also benefits owners. Clients can also cause problems to animals they do not own (Figure 2.5).

Owner causes do not all involve pathological processes. Nevertheless, they are contagious. How people treat animals can spread to other people, through communicable attitudes, direct contact with established practices, purchases or laws (Table 2.1). In this way, welfare problems may spread like epidemics or become endemic in an industry (e.g. beak-trimming in the poultry industry) or within a small number of people (e.g. tail-docking amongst pedigree dog breeders), which then contaminates others (e.g. puppy buyers).

Figure 2.3 Representation of a theoretical relationship between level of owner interventions (e.g. provisions) and effect on animal welfare.

Figure 2.4 Owners may harm their animal by providing excessive resources. (Courtesy of RSPCA Bristol.)

Fortunately, owners can also prevent and solve welfare problems and can be a useful source of enthusiasm, resources and solutions. Owners can also act to achieve good welfare for their animals, for example by providing them with exercise, mental stimulation and company. The behaviours that cause good welfare are also contagious and people can learn good practices from one another and from veterinary professionals.

Figure 2.5 Clients can also harm animals they do not own, such as this bat caught in flypaper. (Courtesy of RSPCA Bristol.)

Table 2.1 Modes of transmission of contagious welfare practices.

| Source | Mechanism | Example |

| Communicable attitudes | Communication of beliefs | Discussion fora (direct, social, internet) |

| Direct contact with established practices | Conscious imitation | Emulating good farms |

| Accidental mimicry | Copying other jockeys’ riding styles | |

| Purchases | Positive reinforcement | Perpetuating intensive farming systems |

| Law-making | Negative reinforcement | Prohibiting onychectomies in cats |

Owners are responsible for how they treat their animals, whether well or badly. However, this does not mean that the veterinary professional does not have a responsibility as well. A veterinary professional has a responsibility to the animal, even if this involves working on as well as working with the owner. Unfortunately, each veterinary professional’s animal welfare account is partly based on the animal welfare accounts of their clients.

2.2. Owners and the Law

How much veterinary professionals can achieve, and therefore for how much we can be responsible, depends on the circumstances. We are especially constrained by the law in each country, especially those relating to the legal relationships between owners and their animals and between veterinary professionals and their clients.

The legal relationships between owners and their animals in most countries usually give owners certain rights over their animals. The most obvious right is that of property. This allows owners to do many things to their animals, including sell them, use them, destroy them and to gain any benefits that derive from them.

In most countries, owners’ property rights are not absolute. Sometimes owners can legally own animals only under certain conditions (e.g. licences for keeping dangerous wild animals). Often, owners cannot use their animals in any way whatsoever (e.g. owners cannot use their dog to kill their neighbour). Some laws can allow the state to deprive owners of their animal or to disqualify them from owning or using animals in the future, after their conviction for an offence.

In many countries, owners’ rights are constrained by laws that protect the animals themselves. Owners are restricted by the generic laws described in Section 1.2, which apply both to an owner and anybody else’s. Paradoxically, these laws may allow owners to harm their animals more than they can harm other people’s, for example it may be legal for a farmer to put their own sow in a gestation crate but illegal cruelty for them to do it to someone else’s. Some countries place more demanding legal responsibilities on owners to care for their own animals. In EU countries, farmers should take reasonable steps to protect the welfare of animals under their care and avoid those animals being caused any unnecessary pain, suffering or injury (Council Directive 98/58/EC). In the UK, such a duty of care applies to owners of all animals, who must ensure the needs of their animals are met to the extent required by good practice (Animal Welfare Act 2006).

Property laws also usually prohibit other people from doing things to someone else’s animal. A person may be prosecuted in a criminal court if they take, destroy or damage another person’s animal without their consent. A person may be sued in a civil court for any loss or damage. In most states, the compensation is usually relatively inexpensive, since most animals have limited financial value, but can often include any veterinary fees spent in repairing the damage.

Again, there are limits to the property right that prevents other people from damaging one’s animals. For example, an owner’s animal may be legally killed if it is considered dangerous (e.g. some dog breeds) or for disease control (e.g. in contiguous culling regimes). So veterinary professionals may be allowed to legally damage or destroy another person’s property when they are acting on behalf of the government or when there is an overriding animal welfare concern, such as a suffering animal in an emergency situation.

Table 2.2 Elements of negligence in some countries.

| Element | Meaning | Example of where may not apply |

| Duty of care | Veterinary professional must have some responsibility to the animal | Overriding legal duty, e.g. animal welfare |

| Breach of duty | Unreasonable failure | Mistakes |

| Harm done | A human, e.g. the owner, is caused harm that can be monetarily compensated | Where animal is harmed, but owner is not, e.g. lack of pain relief; veterinary surgeon provides free second surgery to repair iatrogenic damage |

NB: This does not constitute legal advice, and the author cannot be held accountable for any decisions made.

Readers are advised to consult a lawyer familiar with the jurisdiction in which they work.

Veterinary professionals may also destroy or damage another person’s animal when they have the owner’s valid consent. For example, if an owner gives you permission to kill their animal, they cannot later demand compensation, unless their consent is deemed invalid. Consent is usually valid if the person giving it is the legal owner of the animal (or their representative), sufficiently informed (e.g. about the operation), competent to give consent (i.e. can understand the information and make a decision) and free from undue influence (i.e. coercion). Consent allows an owner to refuse or permit treatment; it does not allow them to insist on it. So consent means a veterinary professional can do something; but it does not mean they must.

The ideas of property and informed consent underlie other legal duties that veterinary professionals have towards clients. Criminal laws may describe offences, such as theft and fraud or mandate actions such as data protection. Professional codes may add further duties such as honesty and confidentiality.

Owners also enter into legal relationships with veterinary professionals. These may be written contracts (e.g. in some horse vetting or some farm health planning schemes) but are often tacit or implied duty of care. Entering such relationships can place additional responsibilities onto the veterinary professional. As a specific example, owners can effectively delegate some of their animal welfare duties to veterinary professionals, so that the veterinary professional becomes responsible for their animals’ welfare while they are in the practice, for example by providing food, shelter and, if necessary, emergency euthanasia.

Veterinary professionals’ duty of care means that owners can bring claims against veterinary professionals for failing in that duty of care, for example through breaching confidentiality or negligence (Table 2.2). In many countries, veterinary professionals cannot be automatically successfully sued for every mistake (i.e. mistakes can happen without implying negligence), for any malpractice that does not cause the owner harm (i.e. there is nothing for which to compensate them) or for cases where their duties to the client are overridden by a greater responsibility. Crucially, this may allow situations where duty to their patient overrides duty to their client. This can allow veterinary professionals legally not to offer only options that lead to unreasonable welfare harms or to breach confidentiality to prevent future suffering by reporting an abusive client.

2.3 Owner–Animal Relationships

Owners’ legal ownership of their animals forms a backdrop of their relationships with those animals, but there is more to owner–animal relations than simply that of property, and owners and animals can have very varied relationships (Figure 2.6). Human–animal relationships affect owners’ husbandry methods, willingness to pay for treatment and likelihood to comply with advice. Understanding the different types of relationships can therefore be beneficial (Ormerod 2008) and help to achieve animal welfare improvements.

There are several useful ways to categorise human–animal relations. Often these are phrased in terms of how the humans regard the animals, e.g. as companion animals versus farm animals versus laboratory animals versus wild animals. These descriptions do not accurately map onto species (e.g. feral cats). Less commonly, animal–human relationships can be described in terms of how the animal regards humans, such as tame and wild.

Some owners relate to their animals personally, as individuals. This is well recorded for companion animals, especially in modern crazes like the furry babies movement and rites such as funerals and bar mitzvahs (Dresser 2000; Greenebaum 2004; Kenney 2004). Farmers may not think about farm animals in the same way, perhaps especially with regard to intensively farmed animals, since farmers may own millions of animals (Marcus 2005; Bock & van Huik 2007), and farmers are often described as thinking primarily in economic terms (e.g. Norton & Scheifer 1980; Wallace & Moss 2002). In fact, the situation is often more complex. Some companion animal owners think of their animals impersonally (e.g. puppy farmers) and some farmers relate to individual animals (Holloway 2001), such as in hand-rearing economically unviable orphan lambs (indeed, the term pet possibly originated from the term for such lambs).

One can think of human–animal relationships in terms of the animal welfare account owners have regarding their animal or in terms of whether each party is benefitted or harmed (e.g. by using terms from the ecological literature such as exploitative and symbiotic). We tend to think of companion animals as benefitting from humans and farm animals as being harmed, but owners’ relationships with companion animals and farm animals may both be exploitative or symbiotic relationships, depending on the owner’s welfare account towards the particular animal. One can also think of relationships in terms of dependency. Animals or humans are often dependent on each other for something they need (e.g. for food, survival or emotional support). Dependency does not necessarily imply that animals benefit – animals may be harmed by being dependent on humans if the humans do not provide what the animal needs.

One can also think of owner–animal relationship in terms of owners’ moral viewpoints. Some may think that animals have a right to life or that they are completely disposable. Some may think they have equivalent moral status to humans, others that it is wrong to spend resources on them that could be better used on humans. Some may think that owners should have absolute property rights, others may think of their animals as colleagues. And owners can have very different attitudes to animal welfare and decision-making (Hemsworth & Coleman 1998; Boivin et al. 2003; Austin et al. 2005; Hemsworth 2007). These moral positions can obviously be different to our own, and sometimes in surprising ways, for example owners often consider killing an animal to be cruel, even where many veterinary professionals would consider keeping the animal alive to be cruel.

Characterising owner–animal relationships is useful but difficult. Different owners may have different relationships with different animals. Indeed, a single owner may have different relationships with the same animal. For example, an eventer may be a pet, a resource and a financial investment, and the owner may interchange or combine these relationships. Veterinary professionals need to recognise and respond to these different relationships.

2.4 Owner Decision-Making

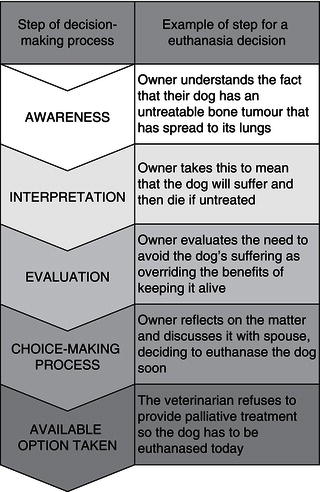

Figure 2.7 shows a model of owners’ decision-making. Understanding their decision-making process is vital for achieving good animal welfare, at all steps of their decision-making (Table 2.3).

The final step (Step 5) is the most important for welfare because it is an owner’s behaviour that alters their animal’s welfare. This behaviour may be straightforward, such as giving consent and payment, or it can be more demanding, such as committing to provide long-term aftercare. In some cases, this step can be emotionally charged, such as the act of killing an animal. Behavioural changes from previous behaviours may require some more demanding decision-making and particular motivation to maintain them.

Performing a desired behaviour requires that owners formulate a genuine intention to perform that action. In most cases, the intention occurs only just before the action. But sometimes, these two steps can be temporally separated. For example, an intention to euthanase an animal may be made at home, but fulfilling that intention can involve both a time delay and a number of intervening steps. This gap allows owners to change their mind if the intention was not strong enough and the underlying reasoning was not sufficiently robust.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree