CHAPTER 18 CHINCHILLAS

COMMON SPECIES KEPT IN CAPTIVITY

There are two species of chinchilla that are kept in captivity: Chinchilla laniger (or lanigera) and C. brevicaudata.1,2 C. laniger is the species commonly kept in captivity in the United States. Originally imported into the United States to provide a commercial fur, these long-lived rodents make excellent pets.

BIOLOGY

Unique Anatomy and Physiology

Chinchillas are native to the semiarid mountainous areas of South America, particularly the countries of Peru, Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile.1,2 Most of the chinchillas kept in the United States are descendants of a small group of animals imported into California in the 1920s.1 Because of overhunting for its beautiful coat, the chinchilla is believed to be nearly extinct in the wild. Wild-type chinchillas have a silver-gray coat with black ticking. Today, there are a number of different coat color variations that have been developed as a result of the fur, show, and pet chinchilla trades. Because the captive chinchillas found in the United States originated from a very small number of animals, a genetic component is suspected in many of the commonly seen disease processes.

Adult chinchillas usually weigh between 400 and 800 g, females being slightly larger than males. Relative to other rodent species, the life span of the chinchilla is long, sometimes nearing 20 years of age.1 Chinchillas are naturally nocturnal, but they can adapt to a more diurnal lifestyle.

HUSBANDRY

Creating an Appropriate Habitat

TEMPERATURE/HUMIDITY

Because of their dense hair coat, chinchillas are not tolerant of temperatures greater than 80° F (26.7° C). That said, chinchillas should be housed indoors throughout the summer. In hot weather, owners should be encouraged to operate the home’s air conditioner to maintain an appropriate temperature for their chinchilla. If this is not possible, alternatives might include using electric fans or placing plastic bottles filled with ice in the chinchilla’s enclosure.

ACCESSORIES

Dust Baths

To maintain proper coat health, chinchillas must be provided with a dust bath 2 to 3 times per week for 10 to 20 minutes (Figure 18-1). The dust used for these animals is a volcanic ash, and commercial brands are readily available. It is important to remove the dust bath from the chinchilla’s enclosure after the bathing period. If the dust bath is not removed, chinchillas tend to bathe excessively, and the prolonged exposure to dust can cause ocular and respiratory irritation.

NUTRITION

Diet

Chinchillas are native to an area of the world that contains sparse vegetation, primarily consisting of grasses. The recommended nutritional composition of a chinchilla diet is 16% to 20% protein, 2% to 5% fat, and 15% to 35% bulk fiber.3 An appropriate chinchilla diet should be comprised of a high-quality hay (e.g., timothy, oat, or orchard grass), chinchilla pellets, and an assortment of dark leafy vegetables (e.g., romaine lettuce, mustard greens, collard greens). Some veterinarians recommend rabbit or guinea pig pellets for chinchillas; however, these pellets are shorter in length than those recommended for chinchillas and are more difficult for these animals to hold. Fruits, grains, and raisins may also be provided as treats on an occasional basis, but they should comprise less than 5% of the animal’s diet. Chinchillas should be provided ad lib access to water in a hanging water bottle.

PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Routine Exams

Many health problems of chinchillas are directly related to improper husbandry. During a routine veterinary visit for chinchilla patients, owners should be asked to provide a detailed description of the animal’s environment, including cage size and type, substrate, frequency of cleaning, ambient temperature, and exercise time. Information pertaining to the animal’s diet, feeding frequency, and bowel movements is also important to obtain.

RESTRAINT

Manual Restraint

Chinchillas are relatively docile and usually do not require aggressive restraint; however, they are capable of quick bursts of activity. A chinchilla that is dropped may injure itself, so appropriate restraint is necessary when examining or transporting these animals. In general, the more a chinchilla is restrained, the more it tends to struggle, so a “less is more” approach should be used. A chinchilla should be restrained by supporting the weight of the body with one hand under the thorax and grasping the base of the tail with the other hand (Figure 18-2). Chinchillas should never be scruffed or handled roughly. Rough handling can result in “fur slip” or the loss of a patch of fur at the site where the animal was grasped. This lost fur can take several months to grow back (see Dermatologic Conditions).

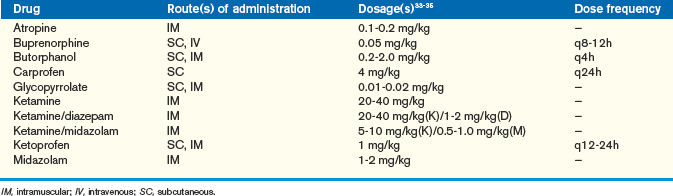

Chemical Restraint

Chinchillas that are fractious or must be anesthetized can be given either parenteral or inhalant anesthetics. We prefer inhalants for these animals, although the parenterals can be used as preanesthetics to limit the concentration of inhalant required for a procedure. Chinchillas can be induced via a face mask with isoflurane or sevoflurane (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL). In general, an induction rate of 3% to 5% isoflurane (per 1 L oxygen) or 5% to 7% sevoflurane (per 1 L oxygen) is required. Chinchillas, like other rodents, are difficult to intubate because of their long, narrow oral cavity. We prefer to intubate these animals using an endoscope. A rigid 2.7-mm endoscope can be used to visualize the airway and direct the endotracheal tube into place. The endotracheal tube size required for a chinchilla can vary, although 2.0 to 4.0 outside diameter tubes are generally acceptable. Once the chinchilla is intubated, the endotracheal tube should be secured and the animal maintained on the inhalant. In general, chinchillas can be maintained at 1.5% to 3.0% isoflurane (per 0.5-1 L oxygen) or 3.0% to 5.0% sevoflurane (per 1 L oxygen). Many of the parenteral anesthetics used for domestic pets can also be used for chinchillas. (For a complete list of parenteral agents please refer to Anesthesia; see also Table 18-6).

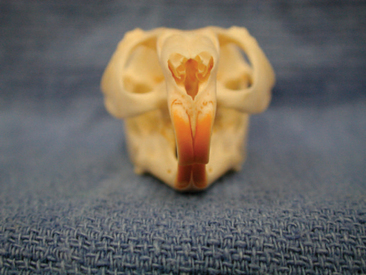

PERFORMING A PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A complete oral examination is another important facet of the chinchilla physical exam. This should be reserved for the end of the examination, as it can be rather stressful for the patient. As is the case for most rodent species, the cranial surface of the incisors is covered with a layer of yellow to orange enamel (Figure 18-3). The oral cavity of the chinchilla has a small opening and is very narrow and long. In most cases, an otoscope with cone or a human nasal speculum is required to fully examine the molars and caudal aspect of the oral cavity. In most cases, the oral exam can be performed on an alert animal; however, anesthesia may be required when the animal is difficult to restrain, appears to be experiencing pain, or requires a more detailed oral exam.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Hematology

Hematologic testing is an important diagnostic tool in chinchilla medicine. Because these prey species can mask their illness, veterinarians must rely on hematologic and other diagnostic tests to fully assess their patients. Box 18-1 presents reference intervals for chinchillas.

BOX 18-1 Hematologic Parameters for Chinchillas

Data from Quesenberry KE, Donnelly TM, Hillyer EV: Biology, husbandry, and clinical techniques of guinea pigs and chinchillas. In Quesenberry KE, Carpenter JW, editors: Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents: Clinical Medicine and Surgery, ed 2, St Louis, 2003, WB Saunders; de Oliveria Silva T, Kruetz LC, Barcellos LJG et al: Reference values for chinchilla (Chinchilla laniger) blood cells and serum biochemical parameters, Ciěncia Rural, 35(3):602–606, 2005.

| Hematologic Parameter | Reference Interval |

|---|---|

| PCV (%) | 30-55 |

| RBC (×106 cells/μl) | 5-10 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 9-15 |

| WBC (×103 cells/μl) | 6-16 |

| Heterophils (%) | 25-50 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 10-70 |

| Monocytes (%) | 0-5 |

| Eosinophils (%) | 0-5 |

| Basophils (%) | 0-2 |

| Platelets (×103 cells/μl) | 300-600 |

PCV, packed cell volume; RBC, red blood cell count; WBC, white blood cell count.

Plasma biochemistries can provide important information regarding the physiologic status of a chinchilla. As with any patient, it is important to interpret the results of a chemistry panel in conjunction with the anamnesis, physical exam findings, and the results of other diagnostic tests. Reference intervals for various chinchilla biochemical parameters can be found in Box 18-2.

BOX 18-2 Plasma Biochemical Parameters for Chinchillas

Data from Quesenberry KE, Donnelly TM, Hillyer EV: Biology, husbandry, and clinical techniques of guinea pigs and chinchillas. In Quesenberry KE, Carpenter JW, editors: Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents: Clinical Medicine and Surgery, ed 2, St Louis, 2003, WB Saunders; de Oliveria Silva T, Kruetz LC, Barcellos LJG et al: Reference values for chinchilla (Chinchilla laniger) blood cells and serum biochemical parameters, Ciěncia Rural, 35(3):602–606, 2005.

| Biochemical Parameter | Reference Interval |

|---|---|

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 130-170 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 3-7 |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 110-130 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 80-125 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dl) | 10-40 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.8-2.3 |

| Calcium (mg/dl) | 8-15 |

| Phosphorous (mg/dl) | 4-8 |

| Total protein (g/dl) | 5-8 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 2.5-4.0 |

| Globulin (g/dl) | 3.5-4.2 |

| Creatine kinase (IU/L) | 0-300 |

| Aspartate transferase (IU/L) | 15-100 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 10-70 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.6-1.3 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 40-300 |

Diagnostic Imaging

Whole body radiographs can provide a significant amount of information regarding the status of a chinchilla patient. A minimum of two radiographic views should be taken. Our preferences are for lateral and ventrodorsal (or dorsoventral) views (Figures 18-4 and 18-5). Care should be taken to extend the limbs when positioning the patient, to minimize rotation and the superimposition of the limbs over the abdomen or thorax. Chinchillas typically resent aggressive restraint, so sedation or anesthesia is helpful in obtaining diagnostic radiographs as well as in reducing the stress on the patient. Table 18-1 is intended as a general guideline for the techniques used for chinchilla radiographic studies.

TABLE 18-1 Guidelines for Radiographic Techniques for Selected Radiographic Studies in Chinchillas

| Anatomic location | mA | kVp |

|---|---|---|

| Whole body | 5.0 | 44 |

| Extremities | 6.0 | 54-56 |

| Skull | 6.0 | 48-52 |

kVp, kilovolt peak; mA, milliampere.

Data from Silverman S, Tell LA: Radiology equipment and positioning techniques. In Silverman S, Tell LA, editors: Radiology of Rodents, Rabbits, and Ferrets: An Atlas of Normal Anatomy and Positioning, St Louis, 2005, WB Saunders.

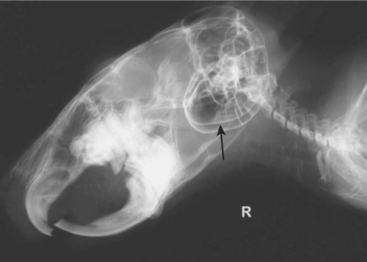

Dental malocclusion is a common problem in chinchillas. Skull radiographs can be used to fully assess the degree of malocclusion and secondary bony involvement (Figure 18-6). When taking skull radiographs, it may be necessary to take 3 to 4 different views. In addition to the standard lateral and dorsoventral (or ventrodorsal) views, right and lateral oblique views can be used to more specifically localize lesions. Magnified views of the skull can be obtained by placing the patient on an elevated platform under the x-ray beam without changing the distance between the x-ray cassette and the beam.

Advanced imaging techniques, such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), can also be used to assist in the diagnosis of disease in chinchillas. CT imaging is particularly useful in diagnosing dental problems, such as apical abscesses, osteomyelitis, and minor malocclusions not readily seen on oral examination or radiographs (Figure 18-7). The primary limitations associated with these imaging modalities include limited availability to the general practitioner, the expense associated with the collection and interpretation of the image, and reduced image quality in comparison with that of larger patients. MRI has the added limitation of requiring a significant amount of time (often >45 min) to collect the image.

Regardless of the present limitations associated with these advanced imaging modalities, veterinarians should be made aware that these techniques are available and that reference material exists that depicts normal anatomy for comparison.5 As chinchilla owners continue to demand high-quality care for their pets, these imaging techniques will likely become more commonplace in exotic small mammal practice.

Microbiology

Chinchillas are susceptible to many of the same pathogens that affect domestic species. The primary pathogens isolated from chinchillas include Gram-negative bacilli (e.g., Bordetella spp., E. coli, Klebsiella spp., Salmonella spp., Pseudomonas spp.) and Gram-positive cocci (Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus spp.). Many of these organisms are opportunists and can be routinely isolated from healthy animals. Samples being submitted for bacterial culture should be collected using sterile swabs and submitted to a diagnostic laboratory capable of isolating and characterizing a range of organisms. The majority of the samples being submitted from chinchillas are for aerobic isolates and require no special attention regarding collection or submission. However, if an anaerobic infection is suspected, it is important to contact the local laboratory to obtain the appropriate materials to collect and submit the samples.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree