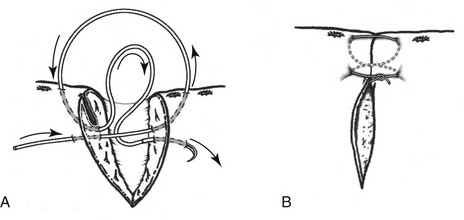

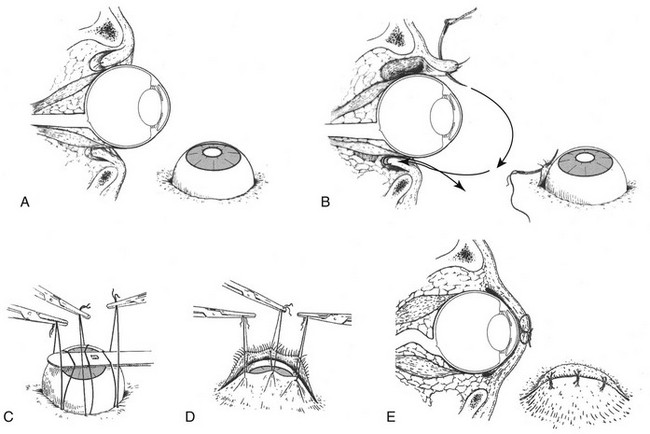

Web Chapter 78 A complete physical examination and assessment of the patient’s fitness for general anesthesia should be performed before replacement of a proptosed globe. Globe replacement should be performed under general anesthesia after the patient’s condition has been stabilized (Web Figure 78-1). First, the eyelids are gently clipped and cleaned. A lubricating gel or ointment should be applied to protect the corneal surface. Using 4-0 nonabsorbable monofilament suture, two to three horizontal mattress sutures are then pre-placed through the eyelids starting 5 to 8 mm distal to the margins. Care should be taken to ensure that the sutures are not full thickness because penetration of the lids through the palpebral conjunctiva leads to corneal ulceration. A lateral canthotomy may aid in replacing the globe. While the sutures are pulled upward to evert the eyelids, gentle pressure is placed on the globe using a scalpel handle or other flat, smooth instrument. Stents may be required to relieve tension on the skin sutures. The medial canthus may be left open to facilitate administration of topical medications. Web Figure 78-1 A, Cross-sectional and lateral view of a prolapsed eye. B, First suture placement in the eyelid. C, Replacement of a proptosed globe showing simultaneous tension on the sutures and downward pressure on the globe using a scalpel handle. D, Replacement of the globe and tightening of the sutures. E, Final appearance of the replaced globe and temporary tarsorrhaphy. (Modified from Severin GA: Severin’s veterinary ophthalmology notes, ed 3, Fort Collins, CO, 1995, Severin, with permission.) Repair should be performed under general anesthesia. Gentle clipping and surgical preparation should be performed. A two-layer closure is required for full-thickness wounds. Apposition of the eyelid margins should be performed first, using 5-0 or 6-0 absorbable suture (Web Figure 78-2). Meticulous care should be used to realign the eyelid margin properly and tie the knot away from the margin. The remainder of the subcutaneous tissue may be closed with a simple interrupted pattern, but placement of full-thickness sutures that penetrate the palpebral conjunctiva should be avoided. The skin then should be apposed with 5-0 nylon or silk. Home care consists of use of an Elizabethan collar to prevent self-trauma and broad-spectrum topical and systemic antibiotic therapy. • Failure to heal within 7 to 10 days • Increasing depth despite the use of standard treatment for an uncomplicated corneal ulcer • Change in stromal character (e.g., a melting appearance) • Presence of corneal neovascularization Please see Chapter 246 for more information about corneal ulcers.

Ocular Emergencies

Proptosis

Eyelid Laceration

Corneal Ulceration

Chapter 78: Ocular Emergencies

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree