Chapter 21 Case Descriptions

This chapter was written for the second edition of this textbook, and despite the change for this third edition to a case-based format throughout the book, we decided to retain most of this chapter in its original form and have added a few new bonus cases. Consider this chapter a test of what you have learned from the preceding chapters. The format is the same as that used for the case examples throughout the book. You must appreciate that magnetic resonance (MR) and computed tomographic (CT) imaging were not available when many of the patients in the original case descriptions were studied.

Signalment: 4-year-old female Great Dane mixed breed

Chief Complaint: Abnormal gait

Inflammations in the medulla of the dog do not commonly cause such specific cranial nerve deficits. An abscess at this level would most likely result from the intracranial extension of a suppurative otitis media-interna, and the history and clinical signs did not support the diagnosis of an otitis. In addition, you would expect this lesion to also cause a facial paralysis. The focal form of granulomatous meningoencephalitis (GME) often occurs in the caudal brainstem, cerebellum, or both. This lesion would not readily explain the initial clinical signs of partial dysphagia or the anisocoria. These clinical signs are best explained by an extracranial lesion in the vicinity of the tympanooccipital fissure. The caudal fossa is a site where congenital epidermoid or dermoid cysts are most common, but they would not be expected to cause the asymmetric cranial nerve clinical signs observed in this dog. Degenerative disorders were not considered because of the anatomic diagnosis.

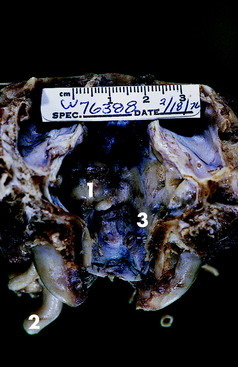

Necropsy revealed marked enlargement of the vagosympathetic trunk in the cranial cervical region. This enlargement included the distal ganglion of the vagus nerve and the cranial cervical ganglion (Fig. 21-1). This nerve enlargement extended into the cranial cavity through the tympanooccipital fissure and jugular foramen. Within the cranial cavity, this mass measured 14 mm in diameter and compressed the medulla caudal to the trapezoid body and cranial nerves VII and VIII (Figs. 21-2,21-3). The intracranial portion of the hypoglossal and accessory nerves were distended with neoplasm. Cranial nerves IX and X were directly involved with the neoplasm. On microscopic examination, the neoplasm was diagnosed as a malignant nerve sheath neoplasm. This neoplasm more commonly affects the trigeminal nerve in our experience and results in unilateral atrophy of the muscles of mastication.

Figure 21-2 Dorsal view of the caudal cranial fossa of the skull in Fig. 21-1. The neoplasm (1) on the left is continuous through the jugular foramen and tympanooccipital fissure with the enlarged vagosympathetic trunk (2) and associated ganglia seen in Fig. 21-1. Note the normal jugular foramen (3) with branches of cranial nerves IX, X, and XI in it.

Figure 21-3 Ventral surface of the preserved brain of the Great Dane mixed breed in this case example. Note the depression on the left side of the medulla (1) just caudal to the vestibulocochlear nerve and trapezoid body caused by the neoplasm seen in Fig. 21-2.

Signalment: 11-year-old female collie

Chief Complaint: Inability to use the pelvic limbs

At necropsy, a large firm nodular mass was found in the thorax on the surface of the left longus colli muscle involving the cranial aspect of the thoracic sympathetic trunk and left cervicothoracic ganglion. The mass extended dorsally between the first two ribs and entered the vertebral canal through the intervertebral foramen between the first and second thoracic vertebrae. It compressed the left first thoracic spinal nerve and expanded into the epidural space where it compressed the spinal cord to the right side (Fig. 21-4). The second and especially the third spinal cord segments were the most compressed. The third thoracic spinal cord segment was compressed to less than one half of its normal width. On microscopic examination this neoplasm was diagnosed as a malignant nerve sheath neoplasm.

This case emphasizes the importance of doing a complete neurologic examination regardless of the chief complaint. Recognition of Horner syndrome was especially of value in localizing the level of the lesion in the spinal cord of this dog. This syndrome probably occurred before the gait deficit if it can be assumed that the sympathetic trunk and cervicothoracic ganglion were affected by the neoplasm initially before the neoplasm extended into the vertebral canal. Most extramedullary spinal cord neoplasms are good candidates for surgical removal. However, recurrence is common for this nerve sheath neoplasm, given that removing all the neoplastic cells is impossible. Surgery or radiation therapy would not likely have significantly altered the long-term outcome in this dog given the location of the lesion in the thoracic sympathetic trunk and the relatively aggressive nature of this particular neoplasm. These types of neoplasms are readily identified by CT or MR imaging. See Video 7-2 and Case Example 7-1 for a similar disorder.

Signalment: 8-year-old male coonhound mixed breed

Chief Complaint: Unable to stand up

Anatomic Diagnosis: Caudal cranial fossa—cerebellum, pons, and medulla

Despite the breed and use of this dog and the observed exposure to raccoon bites, these clinical signs are the antithesis of the clinical signs of polyradiculoneuritis of coonhound paralysis, which are diffuse neuromuscular signs. The vestibular system dysfunction was severe with the head tilt, the leaning to one side, the abnormal nystagmus, and the strabismus. The spastic tetraparesis and general proprioceptive (GP) ataxia and decerebellate posture clearly indicate that the clinical signs of vestibular system dysfunction are caused by involvement of its central components. Note that the direction of the abnormal nystagmus also supports a central lesion in this system. The decerebellate posture implicates dysfunction of the rostral portion of the cerebellum. The spastic tetraparesis and GP ataxia support involvement of the pontomedullary UMN and GP systems, with the left side more affected. At this level, the UMN system is primarily ipsilateral to the limbs it controls. The portion of the GP system primarily involved here on the left side would be the spinocerebellar tracts, which are also primarily conducting sensory information from the ipsilateral left limbs. The loss of the left medial lemniscus may contribute to the right limb deficits. The predominance of right-sided central vestibular system clinical signs may reflect an asymmetric bilateral caudal cranial fossa lesion or a multifocal lesion, or these may be paradoxical vestibular clinical signs from a left-side lesion involving the left cerebellar peduncles.

Differential Diagnosis: Neoplasm, focal inflammation, epidermoid or dermoid cyst

Ancillary Studies: Radiographs revealed an oval, hyperdense lesion that engulfed the tentorium cerebelli (Fig. 21-5). A meningioma or sarcoma was suspected to be the cause of this hyperdense mass lesion. Cisternal CSF on day 2 of hospitalization contained 14 mononuclear cells/mm3 (normal <5) and 98 mg/dl of protein (normal <25). A second cisternal CSF obtained on day 4 of hospitalization contained 40 white blood cells (WBCs)/mm3, most of which were mononuclear cells, and 176 mg/dl protein. The CSF opening pressure was 265 mm water (normal <180). These ancillary results were compatible with an extramedullary neoplasm involving the tentorium cerebelli, causing compression of the cerebellum and caudal brainstem. Be aware that obtaining CSF from a dog with an intracranial space-occupying lesion has the risk of possible brain herniation secondary to increased intracranial pressure. Today, a delay in obtaining CSF until after advanced imaging has determined the nature of the brain lesion is usually standard procedure.

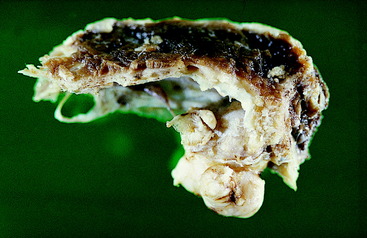

Necropsy confirmed the presence of a large very firm nodular mass that enveloped the tentorium cerebelli (Fig. 21-6) and primarily projected ventrally where it severely compressed the rostral and central portions of the cerebellum (Figs. 21-7,21-8). At the most compressed level of the cerebellum, it only measured 7 mm in height. The caudal cerebellar vermis projected caudally into the foramen magnum. The entire pons and medulla were compressed by the adjacent cerebellar compression. Dorsal to the tentorium cerebelli, the neoplasm compressed the medial portions of both occipital lobes. On microscopic examination, the neoplasm was diagnosed as an osteogenic sarcoma.

Figure 21-6 Lateral view of the preserved calvaria from the skull of the dog in Fig. 21-5, showing an osteogenic sarcoma involving the tentorium cerebelli.

Figure 21-7 Dorsal view of the preserved brainstem and cerebellum of the dog in Figs. 21-5 and 21-6. Note the deep depression in the center of the cerebellum where the tentorial neoplasm was removed with the calvaria.

Signalment: 3-year-old female setter mixed breed

Chief Complaint: Abnormal pelvic limb function

The femoral nerve and its L4 and L5 spinal cord and spinal nerve components were normal based on the normal patellar reflexes and normal nociception from the medial side of the paw and crus via the saphenous nerve branch of the femoral nerve. The normal cutaneous sensation over the cranial thigh resulted from the unaffected lateral cutaneous femoral nerve (L3 and L4) and over the proximal medial thigh from the intact genitofemoral nerve (L3 and L4). The normal hip flexion resulted from the intact innervation of the psoas major muscle from the ventral branches of most of the lumbar spinal nerves. The bladder paralysis requires a bilateral loss of the pelvic nerve innervation (S1, S2, and S3) The loss of the left perineal reflex, nociception, and anal tone requires dysfunction of the left pudendal nerve or its sacral plexus and nerve origin on the left side. The tail deficit requires a bilateral loss of caudal spinal cord segment or spinal nerve innervation.

Ancillary Studies: Radiographs revealed a right coxofemoral joint luxation with a craniodorsal dislocation of the right femur, a fracture of the sacrum at the left sacroiliac joint with subluxation, and a fracture of the sacrocaudal articulation with complete ventral displacement of the caudal vertebral portion (Figs. 21-9,21-10). The ventral branches of the L6 and L7 spinal nerves that contribute to the formation of the sciatic nerve course caudally on the ventral surface of the sacroiliac joint to be joined by the ventral branches of the first and second sacral spinal nerves to form the sciatic nerve at the level of the greater ischiatic notch of the ilium. The skeletal lesions seen here correlate well with the anatomic diagnosis and the clinical signs observed in this dog. Remember that your neurologic examination determines a functional abnormality in the nervous system and not the structural basis for it. Therefore be cautious about your prognosis, especially with injuries such as this one.

Figure 21-10 Lateral radiograph of the pelvis of the dog in Fig. 21-9, showing the sacrocaudal fracture and the luxated right femur. Note the asymmetry of the ilia caused by the subluxation of the left sacroiliac joint.

Signalment: 8-year-old female terrier mixed breed

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree