Pain and stress recognition

Familiarity with the individual dog’s normal behaviour allows identification of any changes brought about by the presence of pain. A dog in pain or distress may show physiological or behavioural signs (see Table 12.1). They may whimper or howl, and growl without provocation. They may bite and scratch at painful areas and may become more vicious or aggressive. The animal may guard a painful area by altering its normal behaviour to avoid moving it.

Table 12.1 Signs of pain and distress in dogs15.

| Physiological signs |

| Increased or decreased respiratory rate, or panting |

| Pallor, cyanosis or jaundice |

| Poor skin and coat condition |

| Discharge from eyes, nose, urinary or genital tracts or ears |

| Increased or decreased body weight |

| Vomiting or diarrhoea |

| Increased or decreased appetite or water consumption |

| Increased or decreased urination |

| Shivering |

| Abnormal posture: hunched, tense or guarded abdomen |

| Behavioural signs |

| Dullness, depression or lethargy |

| Unresponsiveness |

| Increased aggression |

| Increased sleep time |

| Isolation from group or hiding |

| Vocalization |

| Restlessness |

Common diseases and health monitoring

The major risks for disease entry in dog colonies are personnel or new arrivals. Disease entry can be minimised by providing quarantine facilities and serological screening for new arrivals, and by personnel adhering to strict entry requirements. New arrivals should be acquired from known sources with clean health records, effectively quarantined on arrival, and given a veterinary health check as soon as possible.

There should be a regular health monitoring and preventive care programme, including regular veterinary health checks, routine screening and investigation of any unusual occurrences and illnesses. Routine laboratory screening every 3 months is recommended16. Samples of blood, skin/hair and faeces should be analysed for a range of diseases. Most of the major diseases of dogs are preventable by regular vaccination: screening for these diseases in vaccinated dogs is not necessary. Other diseases can be prevented by adhering to strict entry requirements, good hygiene and by regular preventive treatments.

Dogs can be vaccinated against canine adenovirus, canine distemper, canine parainfluenza virus, canine parvovirus, Bordetella bronchiseptica and leptospirosis. They may also develop clinical disease caused by coronavirus, rotavirus or parasite infestations. Zoonotic diseases potentially carried by dogs include leptospirosis, rabies, Salmonella, Campylobacter, Toxocara canis, Lyme disease and brucellosis. Many of these can also affect research; for example, respiratory pathogens compromise studies involving anaesthesia and Toxocara affects toxicological pathology studies.

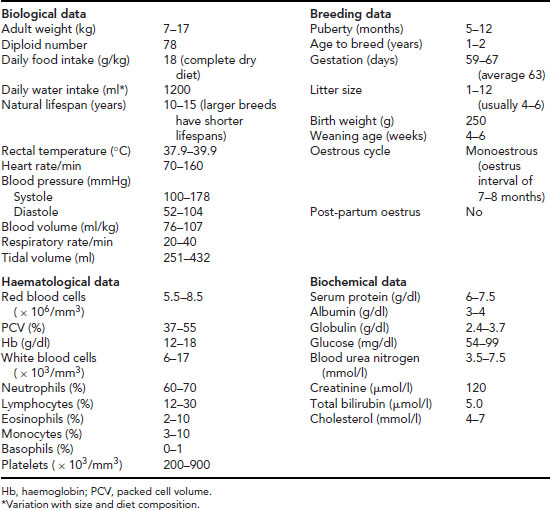

Biological data and useful reference data

See Table 12.2.

Table 12.2 Useful data: dog (beagle).

Anaesthesia

A period of at least 12 h starvation should precede anaesthesia in the dog. It is not necessary to withold water. It is usual to induce anaesthesia by intravenous injection following suitable premedication, then to maintain anaesthesia by inhalation using isofluane and oxygen with or without nitrous oxide. Premedication is essential to alleviate any anxiety and ensure a smooth induction and recovery from anaesthesia. See Table 9.3c for doses for premedication, anaesthesia and analgesia in dogs.

Ferret

The ferret, Mustela putorius furo, is important as a laboratory animal because it is a carnivore that is small enough to be kept easily in the laboratory. There are two main varieties, the fitch ferret, which is buff with a black mask and points, and the albino. Both male and female ferrets show marked seasonal variations in the hair coat, and body weight fluctuates by up to 30–40%, as subcutaneous fat is laid down in the autumn and shed in the spring17. Male ferrets are called hobs, and females jills.

Domestic ferrets are believed to be a domesticated form of the wild European polecat. They appear to have been used by humans for at least 2500 years. References to ferret-like animals used for hunting have been found in ancient Greek and Roman records17,18. Ferrets have been used for hunting, and for the control of rodents and snakes. They can be trained to work on leads or lines and have been used to lay cables. They have also been bred for their fur, known as fitch. Ferrets are still used for hunting today but increasingly are kept simply as pets.

The domestic ferret belongs to the family Mustelidae which includes stoats, weasels, badgers and mink. All mustelids secrete a strong smelling musk from their anal glands, and ferrets are no exception. Their Latin name, Mustela putorius furo, translates as ‘weasel-like smelly thief’.

Mustelids typically have sleek, flexible, elongated tubular bodies, with short legs and small rounded ears. These characteristics allow them to move freely and turn round in confined spaces.

Behaviour

Ferrets are domesticated animals, and are not generally found in the wild. Studies of feral ferrets and the European polecat suggest that they are largely solitary19. However, domestic ferrets are sociable and gregarious, and seem to benefit from being kept in compatible groups.

Ferrets are highly intelligent, lively and curious. They spend up to 75% of the day asleep, but the remainder of the time will be very active. They are more active at night20. They like to sleep in dark, enclosed areas. They are agile and like to explore and burrow, and they will make good use of three-dimensional environments containing playthings and multilevel perches. They are not frightened of humans or human environments18. Their curious nature means they are prone to escape through any hole large enough to get a head through. This can have tragic consequences for both the ferret and any rodents or birds housed in adjacent areas21. Housing design should take these factors into account.

Ferrets have an ill-deserved reputation for being aggressive. Although they have retained many of their natural behaviour patterns, they are more docile than polecats. They may bite if nervous, particularly if handled roughly, and may mistake a tentatively approaching hand for food, but otherwise they are usually friendly, particularly if handled frequently from an early age. Females with litters are protective and may also bite. Young ferrets may nip when first handled, but this abates with frequent handling.

Ferrets communicate by using musk glands, which are situated lateral to the anus. The secretion may also be expressed when excited or frightened, or during the breeding season. They also vocalise and produce a number of different sounds: they may hiss and chuckle when playing, and may scream if frightened or threatened.

Housing

Ferrets will demarcate a number of different areas in their accommodation: a sleeping area, an area for food storage, several escape holes and a latrine area. They prefer to urinate and defaecate in one or two latrine areas within the enclosure, often vertical surfaces, keeping the rest of the cage clean, and ferrets can be trained to use a litter box.

Groups of jills without litters, young animals and castrated males (hobbles) can be kept together, although group housing is not advisable for adult hobs, jills with litters and females that are in oestrus or have been mated. Young ferrets will readily play together.

Housing for ferrets needs to be particularly secure. Their slender bodies and extreme flexibility allow them to exploit the smallest gaps, and they are notorious escapers. Ferrets prefer solid floors with bedding such as sawdust or shavings rather than grid floors.

Plastic tubes, boxes and paper bags will add to the richness of the environment, and the animals will readily explore and play with them. Ferrets will make good use of three dimensional space if given the opportunity (see Figure 12.2). However, ferrets are also prone to chewing and eating such objects, so they should be chosen with care to avoid intestinal foreign bodies. For breeding females, nest boxes should be provided to afford security and warmth for kits.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree