7.1 Normal radiographic appearance of the heart175

7.2 Normal cardiac silhouette with cardiac pathology176

7.3 Cardiac malposition177

7.4 Reduction in heart size: microcardia178

7.5 Generalized enlargement of the cardiac silhouette178

7.6 Pericardial disease179

7.7 Ultrasonography of pericardial disease181

7.8 Left atrial enlargement181

7.9 Left ventricular enlargement182

7.10 Aortic abnormalities183

7.11 Right atrial enlargement184

7.12 Right ventricular enlargement185

7.13 Pulmonary artery trunk abnormalities186

7.14 Changes in pulmonary arteries and veins186

7.15 Caudal vena cava abnormalities186

7.16 Cardiac neoplasia187

Cardiac ultrasonography189

7.19 Two-dimensional and M-mode echocardiography: left heart189

7.20 Two-dimensional and M-mode echocardiography: right heart192

7.21 Contrast echocardiography: right heart194

7.22 Doppler flow abnormalities: mitral valve194

7.23 Doppler flow abnormalities: aortic valve195

7.24 Doppler flow abnormalities: tricuspid valve195

7.25 Doppler flow abnormalities: pulmonic valve196

7.1. NORMAL RADIOGRAPHIC APPEARANCE OF THE HEART

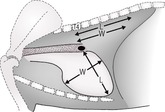

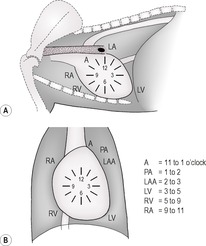

The cardiac silhouette consists of pericardium, pericardial fluid, myocardium (including epicardium and endocardium), the origins of the major vessels and blood. Its size may change with the cardiac cycle, and it may be slightly larger during expiration than inspiration. Its appearance is slightly different between right and left lateral recumbency and between sternal and dorsal recumbency, and so a consistent technique should be adopted. Radiographic signs of heart disease include change in size or shape of the heart and evidence of right- or left-sided heart failure. Alteration in size or shape of the cardiac silhouette may be due to enlargement of any of its components and can often be distinguished only by angiography or ultrasonography; plain radiographs may be misleading. Conformation is the single most important cause for apparent cardiomegaly in barrel-chested dogs such as the Bulldog, Yorkshire Terrier and Dachshund, which have a relatively large heart with elevated trachea on lateral radiographs. The Golden Retriever also has an apparently large and square-shaped heart on the lateral radiograph. Generalized cardiomegaly may be evaluated in dogs by means of the vertebral heart scale measurement (Fig. 7.1); on the lateral recumbent radiograph, the distance between the ventral aspect of the carina and the cardiac apex is taken as a length value, and the maximum width of the heart perpendicular to the length line is taken as the width of the heart. Starting at the cranial aspect of the fourth thoracic vertebra, the number of vertebral lengths is determined for each measurement. In 100 clinically normal adult dogs, the mean (± SD) vertebral heart size was 9.7 ± 0.5. Cardiomegaly is usually considered present when the combined measurement exceeds 10.6 thoracic vertebrae, although in some breeds (e.g. Labrador, Golden Retriever, Boxer, Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, Greyhound, Whippet, Lurcher) this value is commonly exceeded in normal dogs. Reference ranges for some popular breeds have been published. In cats, the same technique can be used with a mean of 7.5 ± 0.3 and 8.1 being the cut-off point above which the heart is considered enlarged. Localized cardiac enlargement may be described according to the clock face analogy (Fig. 7.2).

It should be noted that radiography is an insensitive and relatively inaccurate method for diagnosis of heart diseases (especially congenital), and echocardiography is a much more efficient modality. Nevertheless, radiography is extremely important for assessment of signs of heart failure, especially in the lungs.

7.2. NORMAL CARDIAC SILHOUETTE WITH CARDIAC PATHOLOGY

A normal cardiac silhouette may be present in spite of severe cardiac disease. Echocardiography and an electrocardiogram are essential diagnostic components of the cardiac examination for complete cardiac evaluation.

1. Conduction disturbances and arrhythmias.

2. Over-treated heart disease (e.g. excessive use of diuretics).

3. Concentric ventricular hypertrophy.

a. Secondary to congenital heart disease.

– (Sub)aortic stenosis (left ventricular hypertrophy).

– Pulmonic stenosis (right ventricular hypertrophy).

b. Acquired.

– Idiopathic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in cats and dogs.

– Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy secondary to hyperthyroidism in older cats.

– Systemic or pulmonary hypertension.

5. Endocarditis.

6. Acute myocardial failure.

7. Pericardial disease.

a. Constrictive pericarditis.

b. Acute traumatic haemopericardium.

8. Acute ruptured chordae tendineae.

9. Myocardial neoplasia.

10. Early or mild myocarditis.

7.3. CARDIAC MALPOSITION

Terminology

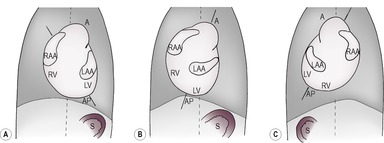

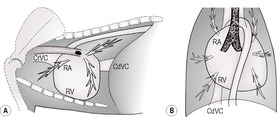

Levocardia – Heart lies in a normal left-sided position (Fig. 7.3A).

Dextrocardia – Heart lying predominantly in the right thorax with the cardiac apex pointing to the right (Fig. 7.3B).

Situs solitus – Normal position of thoracic and abdominal organs.

Situs inversus – Reversal of the normal thoracic and abdominal organs – mirror image (Fig. 7.3C).

Dextrocardia

1. Artefact – incorrectly labelled dorsoventral (DV) or ventrodorsal (VD) radiograph; check the position of the caudal vena cava (CdVC) and descending aorta, or the gastric air bubble and spleen in the cranial abdomen.

2. Normal variant in wide-chested dogs and occasionally in the cat.

3. Acquired causes of dextrocardia.

5. Congenital cardiac abnormalities.

a. Primary dextrocardia with situs inversus (see Fig. 7.3C) – the cardiac apex, left ventricle, aortic arch and gastric fundus all lie on the right side and the CdVC is on the left. –Part of Kartagener’s syndrome (also includes rhinosinusitis and bronchiectasis due to ciliary dyskinesia).

b. Dextrocardia with situs solitus – cardiac chambers normal but apex to right of midline.

c. Levocardia with partial abdominal situs inversus has also been described.

Dorsal displacement of the heart

The heart may also be displaced cranially, caudally, ventrally or further to the left by herniated abdominal viscera or by a variety of mass lesions or bony abnormalities.

7.4. REDUCTION IN HEART SIZE: MICROCARDIA

The heart silhouette is abnormally small and pointed, the ventricles appear narrower and the apex loses contact with the sternum. Thoracic blood vessels may appear smaller and the lungs hyperlucent (see hypovascular pattern, 6.23.5). The CdVC is also reduced in size (Fig. 7.4).

2. Hypovolaemia.

a. Shock.

b. Dehydration.

c. Hypoadrenocorticism (Addison’s disease) – may be accompanied by megaoesophagus.

3. Muscle mass loss.

a. Emaciation.

– Chronic systemic disease.

– Malnutrition.

b. Hypoadrenocorticism (Addison’s disease).

c. Atrophic myopathies.

4. Constrictive pericarditis.

5. Post thoracotomy.

7.5. GENERALIZED ENLARGEMENT OF THE CARDIAC SILHOUETTE

Some of the following diseases may only cause mild cardiomegaly or cardiomegaly only in advanced stages of the condition. Chamber lumen dilation and heart wall hypertrophy cannot be distinguished radiographically, and myocardial pathology is much more readily diagnosed by means of two-dimensional and M-mode echocardiography.

Because it is hard to differentiate the left and right sides of the heart radiographically, disease that is confined to one side may nevertheless appear radiographically as generalized heart enlargement (see 7.8, 7.9, 7.11 and 7.12); the list below includes only diseases that genuinely affect both right and left sides. Assessment of pulmonary vasculature is also important in radiographic assessment of cardiac disease (see 6.23).

1. Normal.

a. Athletic breeds (e.g. Greyhound and other sight hounds).

b. Some young animals.

2. Artefactual.

3. Fluid overload.

4. Bradycardia (e.g. due to sedation), allowing increased diastolic filling.

5. End-stage, left-heart failure due to mitral valve insufficiency.

a. Myxomatous atrioventricular valvular degeneration (endocardiosis).

b. Valvular dysplasia.

c. Bacterial endocarditis.

7. Non-inflammatory myocardial disease.

a. Unknown aetiology.

– Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy – large and giant breed mainly male dogs, 2–7 years old – especially Dobermann, Great Dane, Irish Wolfhound, Scottish Deerhound, Boxer, Dalmatian and Spaniels; juvenile dilated cardiomyopathy in Portuguese Water Dogs. Occasionally seen in cats.

– Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy – rare in dogs (Rottweiler, Dalmatian and German Shepherd dogs may be predisposed); more common in adult male cats.

– Restrictive cardiomyopathy – younger cats, rare; differential diagnosis endocardial fibroelastosis, a congenital condition in Siamese and Burmese kittens and cats under 1 year old.

b. Secondary to a known aetiology.

– End-stage mitral valve insufficiency.

– Nutritional deficiency (e.g. carnitine).

– Toxic (e.g. cytotoxic drugs such as doxorubicin), heavy metals and toxaemia.

– Metabolic disorders, for example hypertrophic cardiomyopathy secondary to hyperthyroidism (especially in older cats) and hyperadrenocorticism.

– Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy – Boxers, inherited; also cats: massively dilated right chambers.

– Cats – dilated cardiomyopathy; nutritional deficiency such as taurine, now rare due to dietary supplementation.

– Cats – dilated cardiomyopathy possibly genetic in Siamese, Burmese and Abyssinian.

– Cats – hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is genetic in Maine Coon cats.

– Cats – acromegaly (hypersomatotropism) may cause hypertrophic, occasionally dilated, cardiomyopathy.

– Cats – hypertrophic feline muscular dystrophy; also diaphragmatic changes.

– Neuromuscular disorders.

– Amyloidosis.

– Lipidosis.

– Mucopolysaccharidosis.

– Infiltrative disease (e.g. neoplasia and glycogen storage diseases).

– Physical agents (e.g. heat and trauma).

– Old age.

8. Concurrent left and right heart valvular insufficiency.

a. Myxomatous atrioventricular valvular degeneration (endocardiosis).

b. Valvular dysplasia.

c. Bacterial endocarditis.

9. Inflammatory myocardial disease.

a. Infectious.

– Viral (e.g. parvovirus in puppies).

– Bacterial.

– Mycoplasma.

– Protozoal (e.g. trypanosomiasis*).

– Parasitic.

– Fungal.

b. Non-infectious.

– Immune-mediated (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis).

10. Ischaemic myocardial disease.

a. Arteriosclerosis and thrombosis of large coronary artery branches.

b. Arteriosclerosis, amyloidosis or hyalinosis of intramural coronary arteries.

c. Angiopathies secondary to congenital heart disease.

11. Chronic anaemia.

12. Hyperviscosity syndrome (e.g. multiple myeloma).

13. Phaeochromocytoma – due to excessive catecholamine production.

14. Pericardial disease – see 7.6.

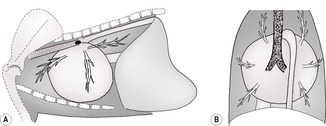

7.6. PERICARDIAL DISEASE

Pericardial disease may be difficult to distinguish from generalized cardiomegaly radiographically. The main difference is that most cases of cardiomegaly have left atrial enlargement, whereas pericardial effusion produces an enlarged, globular cardiac silhouette lacking specific chamber enlargement (Fig. 7.5). Its margins may be sharp due to reduced movement blur. Pericardial effusion may also often be differentiated from generalized cardiomegaly by the type of failure that results, which is right-sided, whereas left-sided or generalized failure is seen with the most common cause of generalized cardiomegaly, cardiomyopathy. Ultrasonography is the imaging modality of choice to evaluate pericardial pathology (see 7.7).

1. Artefactual appearance of pericardial effusion – obese animals may have large amounts of intrapericardial and mediastinal fat mimicking an enlarged cardiac silhouette and possible pericardial effusion. Fat is less radiopaque than soft tissue such as the myocardium, and on good-quality radiographs the pericardial fat can be distinguished from the myocardium; contrast can be enhanced by obtaining radiographs using lower kVp exposures. Normal pericardial fat often demonstrates the cardiac contour in animals with pleural effusion in which the heart is otherwise obscured.

2. Pericardial effusion – usually male dogs over 6 years old and weighing more than 20kg.

a. Non-inflammatory pericardial effusions.

– Idiopathic benign effusion, especially in the St Bernard and Golden Retriever; often haemorrhagic.

– Hypoalbuminaemia.

– Right-sided congestive heart failure, particularly feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

– Toxaemia.

– Uraemia.

– Trauma.

– Neoplastic obstruction of lymph and blood vessels at the heart base.

– Associated with a peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia.

b. Inflammatory pericardial effusions.

– Idiopathic benign effusion.

– Foreign body.

– Septic, purulent process sometimes secondary to perforating wounds.

– Tuberculosis.

– Coccidioidomycosis*.

– Steatitis.

– Cats – feline infectious peritonitis is the most common cause.

c. Neoplastic pericardial effusions – usually haemorrhagic (rare in the cat).

– Right atrial haemangiosarcoma, especially in the German Shepherd dog and often associated with pulmonary, splenic or hepatic haemangiosarcoma.

– Heart base tumours (see 7.16.2).

– Mesothelioma.

– Metastatic neoplasia.

– Lymphoma, especially cats.

– Thyroid carcinoma.

– Rhabdomyosarcoma.

d. Haemopericardium.

– Bleeding tumour.

– Trauma (e.g. gunshot, bite wound, sequel to pericardiocentesis).

– Rupture of the left atrium by a severe jet lesion secondary to mitral valve insufficiency – especially Dachshund, Poodle and Cocker Spaniel.

– Coagulopathy.

e. Chylous pericardial effusion – very rare and of unknown aetiology.

3. Congenital peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia (PPDH) – may be accompanied by sternal abnormalities and an umbilical hernia. Gas-filled intestinal loops or faecal material may be seen within the cardiac silhouette; sternal abnormalities may also be present. Often diagnosed only later in life.

4. Pneumopericardium – rare, usually due to trauma and not clinically significant; also reported secondary to positive-pressure ventilation and due to communication with lung bulla.

5. Intrapericardial cyst – rare. If large, mimics a pericardial effusion and may cause tamponade. Young animals; may be associated with a peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia.

6. Pericardial neoplasia – rare; may extend externally (e.g. lipoma).

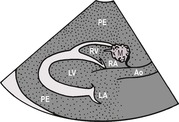

7.7. ULTRASONOGRAPHY OF PERICARDIAL DISEASE

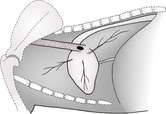

1. Pericardial fluid (see 7.6.2 above). Usually anechoic or hypoechoic fluid. Swirling echoes within the fluid are suggestive of large numbers of cells, debris or gas bubbles. The pericardium may be thickened and distorted if the fluid is inflammatory. It is important to check for the presence of cardiac tamponade secondary to the fluid accumulation; in the early stages this is indicated by collapse of the right atrial wall during systole, and in more advanced cases by abnormal motion of the right ventricular free wall (Fig. 7.6). Right atrial collapse due to pericardial effusion may, however, be mimicked by severe pleural effusion.

2. Intrapericardial mass.

a. Neoplasia.

– Right atrial haemangiosarcoma; seen best on a right-sided long-axis four-chamber view, usually at the junction of the atrium and ventricle and extending into the pericardial sac (Fig. 7.6).

– Heart base tumour; seen best on a right-sided short-axis view just dorsal to the aortic valve.

– Others, listed in 7.6.2c.

b. Thrombus.

c. Abdominal organs in a peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia.

d. Intrapericardial cyst.

3. Thickening of the epicardium or pericardium – may lead to a restrictive state in which complete filling of the cardiac chambers is prevented.

a. Mesothelioma.

b. Reactive or inflammatory changes.

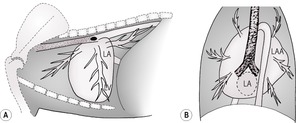

7.8. LEFT ATRIAL ENLARGEMENT

The lateral view shows bulging of the cardiac silhouette at 12–2 o’clock, with elevation and compression of the left main stem bronchus. The caudal border of the heart is abnormally straight and upright or even slopes caudodorsally, and the caudal cardiac waist is lost (Fig. 7.7A). On the DV view, atrial enlargement may push the main stem bronchi further apart (to > 60°) and the enlarged left auricular appendage creates a bulge at 2–3 o’clock (Fig. 7.7B). The increased opacity of the dilated left atrium may be mistaken as lymphadenopathy or a lung mass on either view. Secondary pulmonary changes in the form of vascular congestion or pulmonary oedema may be present (see 6.14 and 6.24).

Volume overload

1. Mitral valve insufficiency.

a. Myxomatous atrioventricular valvular degeneration (endocardiosis) – older, small-breed dogs.

b. Secondary to left ventricular failure when the enlarging ventricle results in dilation of the annular ring (e.g. dilated cardiomyopathy).

c. Bacterial endocarditis.

d. Ruptured left ventricular chordae tendineae.

e. Congenital mitral valve dysplasia – especially Great Dane, German Shepherd dog, Bull Terrier and cats.

f. Ruptured papillary muscle.

2. Diastolic dysfunction of the left ventricle resulting in pooling of blood in the left atrium.

3. Patent ductus arteriosus with left to right shunting – especially German Shepherd dog, Spaniels, Border Collie, Keeshond, Pomeranian, Miniature Poodle and Irish Setter. About 25% of cases show a classic triad of aortic, pulmonary artery and left auricular appendage bulges on the DV view (Fig. 7.8).

4. Ventricular septal defect with left to right shunting – especially Border Collie, Springer Spaniel, West Highland White Terrier, Beagle, Bulldog, German Shepherd dog, Keeshond, Mastiff, Siberian Husky and cats.

6. Endocardial fibroelastosis – Siamese and Burmese kittens.

Pressure overload

7. Left ventricular hypertrophy leading to mitral insufficiency.

a. (Sub)aortic stenosis – especially Boxer, Golden Retriever, German Shepherd dog, Newfoundland, Pointer, Rottweiler, Bulldog and Bull Terriers.

b. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy – rare in dogs; in cats a ‘valentine’-shaped heart is seen on the DV view due to atrial enlargement.

– Idiopathic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; cats and dogs.

– Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy secondary to hyperthyroidism in older cats.

c. Cats – restrictive cardiomyopathy – valentine heart on the DV view.

8. Congenital mitral valve stenosis – especially Newfoundland, Bull Terrier and cats – rare.

9. Cor triatriatum sinister – membranous septum in the left atrium.

10. Atrial or ventricular neoplasia interfering with transvalvular flow – rare.

7.9. LEFT VENTRICULAR ENLARGEMENT

On the lateral view, cardiac enlargement is seen at 2–5/6 o’clock, with increased height of the heart and elevation of the trachea (Fig. 7.7A). Left atrial enlargement is usually also present. On the DV view, the heart may appear elongated and enlargement is seen at 3–5 o’clock; in severe cases this displaces the cardiac apex to the right (Fig. 7.7B) (right heart enlargement due to, for example, pulmonic stenosis may displace the cardiac apex further to the left on the DV radiograph, mimicking left ventricular enlargement).

Volume overload

1. Mitral valve insufficiency (see 7.8.1).

2. Aortic insufficiency.

3. Patent ductus arteriosus with left to right shunting – the most common congenital cardiac condition in the dog but far less common in cats.

5. Endocardial cushion defects (persistent atrioventricular canal).

6. Aorticopulmonary septal defect.

7. Arteriovenous fistula.

Pressure overload

Results in concentric hypertrophy and often does not cause ventricular silhouette enlargement.

8. (Sub)aortic stenosis.

9. Systemic hypertension.

a. Chronic renal failure, especially in cats.

b. Hyperthyroidism.

c. Hyperadrenocorticism (Cushing’s disease).

10. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy – rare in dogs. In cats, a valentine-shaped heart is seen on the DV view due to atrial enlargement.

a. Idiopathic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; cats and dogs.

b. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy secondary to hyperthyroidism in older cats.

c. Acromegaly in cats.

11. Coarctation (narrowing) of the aorta – very rare.

Miscellaneous

15. Ventricular aneurysm – localized protrusion of the left ventricle.

16. Thickened walls due to muscular dystrophy – Golden Retriever and cats.

7.10. AORTIC ABNORMALITIES

1. Enlargement of the aortic arch or descending aorta. On the lateral view, enlargement of the aortic arch may be seen at 11–12 o’clock, with reduction or possibly obliteration of the cranial cardiac waist (Fig. 7.9A). On the DV view, an aortic ‘knuckle’ is seen from 11 to 1 o’clock with mediastinal widening, and there is an apparent increase in the craniocaudal length of the heart (Fig. 7.9B).

a. Post-aortic stenosis dilation – entire aortic arch.

b. Large left to right shunting PDA due to increase in aortic circulating blood volume and inherent aortic wall weakness – predominantly descending part of aortic arch.

c. Aneurysms.

– Secondary to Spirocerca lupi* migration or granulomas – seen as left-sided undulations of the descending aorta on a DV or VD view.

– Idiopathic, with aortic dissection.

– Ductus aneurysm or diverticulum.

– Secondary to coarctation (narrowing of the aortic isthmus, between the left subclavian artery and the insertion of the ductus arteriosus).

d. Aortic body tumour (chemodectoma).

e. Systemic hypertension in cats.

f. Coarctation (narrowing) of the aorta with post-stenotic dilation.

2. Redundant (tortuous or bulging) aorta.

a. Brachycephalic breeds, especially the Bulldog.

b. Some older dogs.

c. Congenital hypothyroidism.

e. Common in old cats, accompanied by a more horizontal heart – aorta bulges cranially and to the left.

4. Calcification or mineralization of the aorta – uncommon and usually an incidental finding. Seen more easily on CT images.

a. Idiopathic, of aortic bulb, aortic valves or coronary arteries; older dogs, especially Rottweilers.

b. Lymphoma.

c. Renal failure.

d. Primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism.

e. Arteriosclerosis.

f. Hyperadrenocorticism (Cushing’s disease).

g. Spirocerca lupi* larval migration – descending aorta.

h. Hypervitaminosis D.

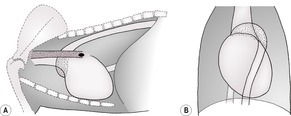

7.11. RIGHT ATRIAL ENLARGEMENT

On the lateral view, bulging of the cardiac silhouette occurs at 10–11 o’clock, with increased craniocaudal dimension of the heart and elevation of the terminal trachea and/or loss of the cranial cardiac waist in severe cases. There may be a widened CdVC as result of venous congestion (Fig. 7.10A). On the DV view, bulging is seen at 9–11 o’clock (Fig. 7.10B). In obese cats, the right atrial area outline may have a square or angular appearance on VD radiographs, due to pericardial fat rather than genuine chamber enlargement.

Volume overload

1. Tricuspid valve insufficiency.

a. Myxomatous atrioventricular valvular degeneration (endocardiosis).

b. Congenital tricuspid valve dysplasia – more common in cats than dogs; also Labrador and German Shepherd dog.

c. Secondary to right ventricular failure when the enlarging ventricle results in dilation of the annular ring.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree