CHAPTER 7 Canine Ingestive Behavior

SUCKLING BEHAVIOR

Nursing by neonates is the start of a dog’s eating behavior. During most of parturition, the bitch shows little interest in nursing any of her puppies. Once they all have been born, though, she quietly presents her mammary surface to them. Newborn puppies have little strength and coordination, so their first attempts to nurse are clumsy and awkward. Because of the rooting reflex, puppies burrow into any warm, soft surface they encounter. This warm, soft surface is usually the littermates or the dam, so this reflex helps ensure that the puppies will find food and warmth. As their heads bob up and down during nursing bouts, they also swing back and forth. The rear limbs move, too, as the puppies try to remain in an upright position. After touching a nipple, the neonate will make several attempts to grasp it and then make several attempts to nurse before being able to achieve proper suction.20,61 Some puppies seem more proficient than others, and most will perfect the technique as they get older.

While the puppy nurses, it makes a rhythmic, kneading movement of its forelimbs against the bitch’s mammary region. This kneading motion may serve one or more purposes. Newborn puppies have a blocky appearance to their face, and the nose does not elongate until the puppy is a few weeks old. Considering the fact that the kneading occurs during sucking and is most consistent in very young puppies, one might speculate that it helps push the mother’s abdomen away from the youngster’s nose.55 A second function might be to help stimulate milk flow via massage of the mammary gland,20 although, in theory at least, massage should come later, as larger puppies require more milk. Also, massage should occur in a suckle-knead-suckle-knead cycle. By 17 days of age, forelimb thrusting is no longer seen in the puppies, and by 21 days, their sucking is no longer rhythmic but has become noisy and irregular instead.55

The lip sucking reflex (Fig. 7-1) helps ensure that newborns will try to nurse on soft projections. It is independent of hunger or food intake.89 If, however, the puppy’s stomach is filled via stomach tube just before being allowed to suckle, the full puppy will spend significantly less time sucking than a puppy that was not full to begin with.137 Sucking can also be non-nutritional, as food-satiated puppies commonly fall asleep while showing sucking behaviors. They also will show sucking behavior again if someone disturbs their sleep. This type of non-nutritional sucking has been called a “comfort behavior.”

During the first 3 weeks, the mother initiates all nursing sessions. She makes the approach, presents the mammary area, and arouses the puppies by licking them. 53 The puppies do not have preferred nipple positions.61,73

Each day a puppy ages brings changes in needs and physiology. Many bacteria are already present in the stomach on the first day.142 In puppies younger than 8 days of age, the stomach usually contains 1 to 5 ml of milk and is very alkaline.131 This condition of the stomach may indicate a need for frequent sucking bouts. The average daily intake is 175 g per day (150 to 175 ml).123 After the eighth day, the puppy’s stomach will hold 10 to 20 ml,142 and milk intake reaches a peak at 26 days.123 At this time, milk can provide 1.5 kcal/g gross energy, and the average bitch can produce 1050 g per day of milk (approximately 1 L).123

TRANSITIONAL INGESTIVE BEHAVIOR

By 4 weeks after birth, puppies start developing the eating behaviors that they will use as adults, yet they continue nursing, too. This is the age at which the young should be introduced to semisolid food. It is also a time when the bitch becomes less cooperative in nursing bouts, so the puppies are more apt to solicit the mother to nurse. She usually cooperates with the solicitations by lying down. After day 30, the young initiate all nursing bouts.73 The bitch is apt to restrict the length of these periods, be gone longer, and even show aggression to the puppies if they attempt to nurse more often than she wishes them to.21,61,110 Their solicitation attempts become increasingly unsuccessful during this period, with the mother remaining standing for the ever shorter nursing bouts (Fig. 7-2). She might even lie down and hide her nipples against the floor.73

In wolves, this is also a time of increased nursing demands by the cubs. To meet this need and help ensure survival of the cubs, the nonpregnant females go through pseudocyesis about the same time that the dominant female is pregnant. Nursing can then stimulate lactation in females that are not the cub’s mother.72

For most puppies, their first solid food is some variety of commercial dog food, either canned or moistened to make it compatible to deciduous teeth and soft gums. Deciduous teeth are in place by 3 weeks and are not replaced until 16 to 26 weeks.107 Care is necessary during this transitional period because sometimes a bitch will aggressively compete with her puppies for available food.61 If she is well fed, this competition for food is unlikely to occur. Variance in flavors in puppy diets is not particularly important to long-term diet preferences in adult dogs,52 but it does help prevent some individuals from becoming picky eaters. Considerable individual variation exists in the amount of milk and solid-food intake by puppies during the transitional period. A significant correlation exists, however, between solid-food intake and the weight of the puppy.108

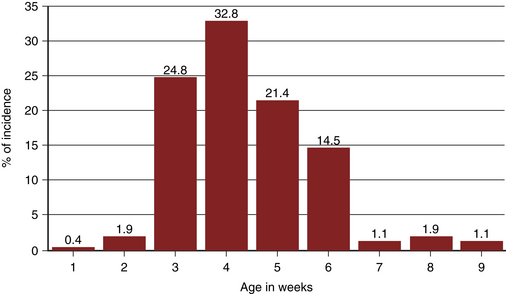

In wolves, semisolid food is introduced to the cubs at 3 to 4 weeks, when the mother and other pack members are stimulated to regurgitate by face licking from the cubs. This behavior allows the adults to carry large amounts of food for the cubs without it being stolen, and it means the young are not exposed to the dangers of traveling with the adults as they hunt large herbivores.96,107 Eating regurgitated food also facilitates the transition from suckling to eating solid food.106 The same type of regurgitation behavior occurs in some dogs.15,106 Almost two thirds of pet dog breeds have displayed regurgitation for puppies on occasion.106 Almost all free-ranging bitches will regurgitate for their puppies and males will occasionally do so too.128 The age of the puppies when the behavior starts varies but usually occurs at 3 to 6 weeks (Fig. 7-3). Although 78% of the time it is the mother that regurgitates food for the puppies, other dogs may be involved.96,106,107 The sire is involved 3% of the time, and other nearby dogs the remainder of the time.106 It takes more effort by the puppies to get other dogs besides the mother to regurgitate.106 The puppies initiate the regurgitation 15% of the time, the adult dog initiates it 29%, and both are equally involved 56% of the time.106

Figure 7-3 Age of puppies when regurgitation from food solicitation first occurs.

(Data from reference 106.)

While the litter remains together, competition for food increases food intake by each puppy until dominance relations have been established.55,61 Puppies will normally eat 14% to 50% more when fed as a group than when fed individually.61,91 If a single puppy is fed until it is “full,” it will eat 30% to 200% more if its hungry littermates are then allowed to eat.61,91 After dominance is established, social facilitation becomes important.90 When social relations develop between group members that are fed together, the dogs will eat more in the group than if fed alone,71,78,90,91 but dominant puppies, simply with their presence, may inhibit some of their littermates from eating as much.

Even though weaning is complete at 7 to 10 weeks in dogs and wolves,107,110 young wolves are not capable of hunting large prey until they are at least 4 months of age.107 To learn the necessary skills and develop appropriate strength, wolf cubs usually do not become independent until 4 to 6 months.107

Non-Nutritional Chewing

Puppies show oral behaviors that are not associated directly with eating. Mouthing behaviors are a normal canine form of exploration and investigation that begin at the onset of socialization—around 3 weeks.55,78 By chewing, licking, carrying, tugging, and even swallowing small objects, a puppy can gain sensory information about its environment (Fig. 7-4). The actual relationship of chewing on objects to teething remains unclear.78 Certain breeds seem to show these behaviors more. Those with mouth-oriented adult traits, like Labrador Retrievers and German Shepherds, are more likely to show a lot of oral activity as puppies. Thus, control measures must be taken so that the mouthing behavior does not become a problem. The use of a crate for young puppies controls their access to objects so their oral activity can be directed to two or three likable chew-toys. Chew-toys can be made more attractive by smearing them with food or by tucking food in the crevices. Praise should be used when the puppy plays with the toy, and a “No” and replacement with an acceptable toy should be used for incidences of inappropriate chewing.86

Coprophagy is also a normal behavior in puppies for a short period.55 Eating the feces from another dog may help a puppy establish normal flora in the intestinal tract, and diet can affect intestinal flora.2 Coprophagy in puppies may simply represent an exploratory behavior. In either case, the owner should not punish the behavior. Instead, the puppy’s attention could be diverted to another activity or access prevented to the feces of other dogs.

ADULT INGESTIVE BEHAVIOR

Once dominance has been established, juvenile eating behaviors are gradually replaced by adult ones. Most wild canids survive with a feast-or-famine type of food intake, because the successful hunting of large game is sporadic.14,27,61,75,124 The tendency with this pattern is to overeat when food is plentiful to get past the times when it is scarce. Dogs tend to retain the feast-or-famine characteristics and will eat more calories than necessary if food is available. When free-choice dry food is available, dogs tend toward eating several meals per day within just a few days.25,133 Individually housed dogs eat whenever fresh food is offered and usually will eat three to six meals per day.78,133 If the dogs are kept in groups instead of singly, however, their tendency is to eat nine to twelve meals per day.78,82 In general, dogs tend to eat more than they need for maintenance,61,92 and it has even been hypothesized that a second set point for body weight may develop when highly palatable food is routinely offered.78 Approximately 70% of dogs will eat a great deal more than they are used to eating if the food is available.25

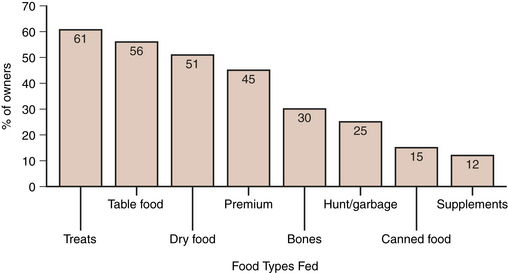

Pet-feeding patterns of dog owners have been studied.33,48,130,141 Only 26% of dog owners feed their pet once a day; others feed their pets more often. Even the dogs that are fed just once a day get treats in addition to their meal. Figure 7-5 shows what types of food—dry and canned dog food, treats, table food, and so forth—are provided.

There are apparently a number of controls for food intake by dogs. For a short time, distention resulting from the bulk of the food is the major factor for limiting intake.55,78,94,139 Caloric content,55,93 body temperature,49,78 ambient temperature,47,78,133 stress,57 oropharyngeal sensory input,94,97 timing of the food availability,133 olfaction,78 taste and texture,75,78 and intestinal chemoreceptors78 also can be restrictive. Food intake will decrease 4% for every 10° F (2° C) rise in environmental temperature.47 The influences of smell on the perception of taste appear to involve a cognitive mechanism.74 Taste appears to influence the perception of smell as well, probably by way of oropharynx to nasopharynx.74 The tendency to adjust daily intake from bulk to caloric needs is modified only slowly.93

Food Preferences

Several studies have been reported on the relative preferences of various foods by dogs. It is important to remember that these preferences are relative, although individual food preferences do exist. A palatable food is one that has some probability of being eaten under some specific conditions.66 Preference has to do with the likelihood that one of two available foods will be eaten under very specific conditions.66 Many types of meals are palatable under certain conditions and not others, and foods that are sometimes regarded as unpalatable can even be highly desirable when the dog is hungry.97 This fact is particularly relevant in regard to dogs that must forage for all or part of their food. Even within the components of garbage, a preference ranking can be determined.16

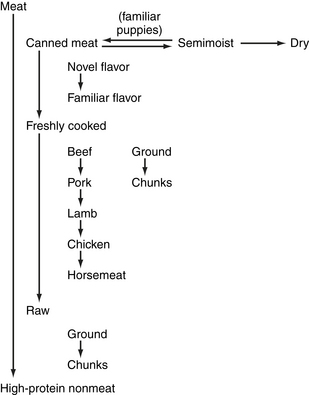

Comparison of food preferences indicates that dogs prefer meat to a food that is high-protein and fatty but nonmeat (Fig. 7-6).78,83 The descending preference order for meat is beef, pork, lamb, chicken, and horsemeat.78,83,103,149 Canned food is usually preferred to semimoist food, and that to dry kibble.78,95,143,149 Canned meat is preferred to the same meat freshly cooked, and the freshly cooked meat is preferred to raw.78,83,103,149 Ground meat is preferred to meat chunks by dogs, and warm rates better than cold.83

A novel canned flavor is preferred initially 90% of the time to a long-term familiar food.52,78,95,159 This is true too in puppies fed a specific food from weaning until 6 months and then offered a novel one.84 If given choices early, palatability and the maternal affect of a dam’s diet flavoring her milk may negate the draw of a novel food.78 If a puppy is familiar with semimoist food, it will prefer it to canned foods.78

Dogs prefer sweet to bland tastes,83,149 so sweet tastes also can be rated by preferences. The predominant taste bud units of the facial nerve of a dog are the type A ones that respond to amino acids.27 Many of these amino acids are described as “sweetish” by people.27 Glucose ranks as the most liked, followed by fructose, sucrose, and table sugar.34,58 Even though sucrose is liked by dogs,65,80,95 fructose ranks higher than sucrose, the opposite of humans and pigs.78 Saccharin and maltose are not liked.65,78 Dogs tend to overeat sweet foods.158 As natural foods do not contain a lot of sweets, nature has developed no method to limit intake of sweet foods.

When the sense of smell is lost through disease, trauma, or experimental manipulation, palatability and preferences are also affected. The preference for meat or sucrose over a bland cereal remains, but preferences in between are eliminated.78,83

Although food preferences rarely pose a problem for dogs, a puppy’s early experience with solid food can influence its choices later. If fed limited diets before 6 months of age, a puppy may continue to choose to eat that particular diet as an adult.71,149 Even later a dog can acquire a preference for a certain food if it is exposed to the odor of that food on the breath of another dog that ate that same food.105 Antidotal reactions to certain are dogs that become very distressed when lamb is cooked.60 Some of these dogs will eat lamb but others will not.

Plant (Grass) Eating

Most owners have observed their dogs eating grass or other plants (Fig. 7-7). Grass eating represents a normal behavior that if carried to excess can be considered a problem. Grass is eaten more often that other types of plants, and there is no correlation with the frequency of eating plants to sex, breed, diet, internal parasite load, or other behavioral problems.145 Instead, the behavior is related to that seen in wolves. Wolves eat large ungulates, with the viscera being a favorite portion of the prey. In eating the abdominal contents, a wolf normally takes in some partially digested vegetable matter. Carnivores lack the ability to break the beta-bonds of cellulose to glucose, which is then converted to volatile fatty acids for absorption, so they depend on a partially digested form instead.9,14 Yet, most dogs will routinely eat small amounts of grass without adverse effects. Problems arise only if the dog has not had access to vegetable matter for a while, as can occur over winter.9,14 They then tend to eat large amounts of grass when they have access to it again. Since they cannot digest this material, it remains as a gastrointestinal irritant until the dog either vomits it up or passes it in the feces.

Apparently some dogs learn to associate plant eating with vomiting and seek out plants at times when they are not feeling well.9,14 The incidence of plant-associated vomiting can be minimized by supplementing the dog’s diet with small amounts of fresh grass or with cooked vegetables (cooking starts the breakdown of cellulose).9,14 Because some plants are poisonous to dogs, it is best to prevent access to any poisonous or favorite household plants.119

Hunting (Predatory) Behavior

Ancestral feeding patterns still play a role in the dog’s ingestive behavior. The order Carnivora literally means “eaters of flesh.”149 Canids have developed sophisticated pack-hunting techniques.96 As the size of the prey hunted by wolf ancestors for their primary food source increased, hunting techniques changed. Pack sizes now typically range from 2 to 12 members, although they can be larger.114 Group hunting allows a pack to locate, chase, kill, and eat large animals more efficiently.114 In theory an individual would have more food available per meal than does a pack member; however, the advantages of group hunting increase the likelihood the hunt will be successful. Also, scavengers are more successful against the individual hunter, so total take is less.157

For Canis lupus, the gray wolf, certain prehunt behaviors are typical. As the pack members get together, there is much tail wagging and activity to motivate the leaders to hunt.114 Once prey is located, the hunting behavior sequence begins. At first, the wolves will stalk the prey animal to get as close to it as possible. Then comes the encounter. As the wolves and prey confront each other, large prey tend to stand their ground, whereas smaller ones tend to bolt.114 The hunters will rush toward the retreating animal. A chase can get up to a speed of 35 to 40 miles per hour and usually does not go for more than 2 miles.114 Success at catching prey from this chase varies from 25% to 63%.114

When the wolves catch smaller prey, they typically throw it down and tear anywhere at its flesh.114 Larger prey are usually attacked from behind in the rump, flank, or rear limbs by several wolves, as one wolf holds the nose of the prey.114 During feeding of the downed animal, pack members tend to stand side by side around the carcass and usually start on the rump and abdomen, tearing in every direction.114 Food is eaten quickly. If space is limited, higher ranking members eat first, juveniles eat last.27 A correlation exists between the size of the prey and either the size of the predator or the number of cooperative predators of the same species.55 All canids have a tendency to bury extra food after they are satiated.129

By 4 weeks of age, some wolf cubs will begin showing predatory behavior toward rats.55 Within a few days of starting this behavior, they will crush the rat immediately and weakly shake it.55 Shaking behaviors will eventually be used to stun smaller prey while strengthening the predator’s grip on its prey.129 Cubs rarely play with their prey in the presence of another wolf.55 They also prefer prey that move and make noise.55

The point of discussing hunting behavior in the wolf is that much of the same behavior is shown by dogs, including orientation toward the prey and attack sites. When dogs attack larger animals, the wounds are often in the perineum and area of the tailhead.3 Slightly smaller victims of dog attacks, like calves, sheep, or ponies, have a predominance of wounds to the rear limbs, head, or neck. The opportunity to successfully stalk is not common for dogs, because truly feral populations are not common, and most dogs do not have access to prey.

Dogs will chase moving objects because prey-chasing behavior is initiated by the sight of something moving rapidly away. The intensity of the urge to pursue increases with the length of the pursuit.129 This is why the dog may chase the family cat when it is in its yard but ignore the cat in the house. Prey-shaking behavior likewise increases with the length of the pursuit. If no chase is initiated, or if the chase is short, prey shaking is likely to be minimal or absent. For example, a rabbit placed immediately in front of a dog is probably much safer than one given a 20-foot head start.

Unlike wolves, the presence of another dog increases the incidence of play directed toward prey. This play behavior includes a lot of prey shaking and throwing of the prey in the air, as well as pawing and nosing.56 Puppies younger than 10 weeks of age typically show attempts to pin down the prey with their front limbs—the forelimb stab—with and without a vertical leap.58 They also show all the various aspects of adult predatory behaviors in fragmented sequences associated with other play behaviors.58 Another feature of the puppy form of play is the inhibited bite.58 Movements and sounds reinforce the various behaviors, and immobility is responded to by nosing and pawing. When the prey tries to escape, its movements are followed by the chase or blockage of escape.56 Even a dead rat will be played with by laying it between the forepaws, nosing, nipping, and tossing it in the air.56 Dominance is not asserted over possession of prey in dogs, which is different than in other canids.56

During a biting attack on prey, all canids will flatten their ears and partially close their eyes.56 When they are striking with a forepaw, their head and neck are raised and arched and the ears pricked upward.56 As with other consummatory behaviors, such as mating and eliminating, the undisturbed canid shows a “consummatory facial expression” with ears partially flattened and eyes partially or fully closed, a pleasure face (see Chapter 3, Fig. 3-5).56

Selective breeding has produced many variations in play behavior. It has been suggested that dogs are the neotenic descendants of some canid ancestor, which means that behaviors like herding or guarding represent the retardation of development that led to the retention of certain ancestral juvenile or embryonic characteristics.38 According to this theory, the livestock-guarding dogs would represent the most juvenile forms because of their physical features of floppy ears and domed skulls.38 The herding dogs have a somewhat less juvenile form, with more adult-shaped skulls and half-erect ears.38 When dogs of various breeds are field tested with goats, most react by barking, stalking, chasing, and attacking.63 Basenjis regularly attack as a pack.63 Other dogs show attack inhibition, which apparently is genetically programmed to take effect at a certain stage of predation. Both sight and smell hounds excel in the tracking or trailing aspect of predation but are less likely to go beyond this point in the behavior sequence. Sheep and cattle dogs have been observed to stop at herding or driving, whereas dogs like Boarhounds and Terriers continue on to the attack/kill stage. Retrievers have the tendency to provision cubs or mates.38,58 Another variation of selective breeding is the dog that guards one species (such as sheep) but will attack other species (like coyotes) as potential predators.38 Stalking and pointing tend to be traits of setters and pointers. Diet has been shown to affect the performance too, with some commercial products resulting in more birds while bird hunting.44

Large herbivores are not the only prey for canids. Dogs will go after rabbits, cats, birds, and occasionally even fish.148 Other small species unique to certain locations also might be consumed, such as poultry, iguanas, or tortoises.7,62 It is suggested that because more than one type of wolf gives rise to dogs, their adaptability to different types of food may be a result of that background.149 No correlation has been found between hunting efficiency and the social rank, size, or sex of the hunter.24 Studies of stomach contents and feces analysis from a feral dog population of free-ranging dogs revealed a variety of foodstuffs, indicating the dogs had been acting as both predators and scavengers. Foods of animal origin included rabbits, mice, songbirds, carrion, and insects.62,138 Other items that dogs can consume include foods of plant origin like grass, leaves, and fruits (especially persimmons).62,138 Maggots, a find in 40% of the samples, indicate that dogs commonly eat decaying tissues.62 With more than 1 million wild animals becoming road kill each year in the United States,62 free-ranging and feral dogs are likely to drag off this readily available food source without detection. Trash also has become a major source of food for dogs.62,125,138 Not only is the uncontrolled dog a nuisance because it breaks open garbage bags, but garbage can be a major food source for some dog populations.62,125,136

WATER CONSUMPTION

Drinking has two components—the behavior and the underlying process that results in water consumption. A dog laps water with its tongue. The tongue is curled backward and serves as a ladle to lift the water into the mouth (Fig. 7-8). Because the curl is almost flat across instead of cup-shaped, much of the water spills out from the sides before the dog can get it into the mouth. Depending on the rate of lapping, size of the tongue, size of the water dish, and distance between the mouth and the water, a dog can dribble water over a large area or keep almost all of it in the water bowl.

The amount a dog drinks each day depends on a number of factors, but the most significant is size. The average dog takes in approximately 1100 ml of water per day.61 Of this amount, approximately half comes from eating food and the other half from drinking.61 On average, a dog drinks nine times per day, averaging 60 ml per time.61 As ambient temperature increases, so does water consumption.133 The regulation of water consumption depends on several things. For a short period, the amount of water passing through the mouth and pharynx can bring a temporary end to drinking.17 A second factor that helps inhibit drinking is distention of the stomach.150 Subsequent permanent satiation follows intestinal absorption150 that exactly replenishes the body’s water deficit,132,134 rebalances plasma sodium levels,76,131,163 and helps restore extracellular electrolyte levels.36 Cholecystokinin, which is released when high-protein or fatty foods are eaten, stimulates gallbladder contraction, increases pancreatic enzyme secretion, and acts as a satiety agent.82

NEURAL AND HORMONAL REGULATION

Several related neurohormonal responses are associated with eating. Gastin, adrenocorticotropic hormone, prolactin, growth hormone, oxytocin, and insulin are released with digestion.151,152,153 The output of somatostatin, an inhibitory peptide, is reduced.151 Pregnancy and lactation are associated with changes in the gastrointestinal hormones that may increase digestive and anabolic capacity.102 During pregnancy, the levels of gastrin, somatostatin, and cholecystokinin increase.102 Somatostatin levels remain elevated during the first week or so of lactation; gastrin and cholecystokinin increase in response to suckling.102,151 Insulin and prolactin levels also rise in response to suckling by young.151,152 Oxytocin levels rise in response to suckling by young, eating by the bitch, and the presence of food in the gastrointestinal tract.151,153

Within the brain, several areas of the hypothalamus affect eating behaviors. The “satiety center” in the ventromedial hypothalamus helps stop the desire for food and is responsible for adipose regulation.99 Experimental stimulation of the ventromedial hypothalamus causes anorexia, and destruction of this area causes hyperphagia. The lateral hypothalamus, or “feeding or hunger center,” is associated with glucose availability.82 Stimulation of this area causes great increases in food intake, even in the satiated. On the other hand, destruction of the lateral hypothalamus results in aphagia. Much of the research relating to the central regulation of eating behaviors has been done in the cat, and the reader is directed to other references for more detailed information.12 The pontine parabrachial nucleus is important for the acquisition of taste aversion.18

Other inputs influence eating behaviors directly or indirectly: environmental temperatures, osmotic pressures in the small intestines, social facilitation, and the taste and smell of food, to name a few.82 Flavor validation is primarily based on olfaction, as can be shown when a trained dog loses as much as 75% of its ability to select a specific meat when made anosmic.81

Psychodietetics is the study of behavior and diet.5 Understanding the relationship between the two can be difficult and constantly undergoes modification as researchers gather new information. Of most interest at the current time is the dietary influence of the amino acids on the neurotransmitters. Tryptophan becomes 5-hydroxytryptophan, which becomes serotonin. Tyrosine is changed to dihydroxyphenylalanine and then to dopamine, which can change to noradrenaline, and that to adrenaline. The third pathway is histidine, which becomes histamine. The last pathway is lecithin, to choline, to acetylcholine, and back to choline. From the amino acids of tryptophan, tyrosine, lecithin, and histidine come six neurotransmitters—serotonin, dopamine, noradrenaline, adrenaline, acetylcholine, and histamine (see Chapter 2, Box 2-1).5